|

Module Six: American Revolution Part 2 (1792 CE- 1819 CE)

Welcome to HST 201 Module Five! We are looking at effects of American Revolution on the North American landscape . History, you are a cruel mistress. Some days you are a fun romp that looks at our past; other days, you are a sad reminder of our shortcomings and failures. Sometimes you are a well-documented account, with 1000s of books written on your behalf. Other times you are a convoluted mess, an untidy murder scene riddled with more questions than answers. Either way, rule number 6 of history: No cherry-picking. For those unfamiliar with the concept, cherry-picking is the act of pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a position while ignoring a significant portion of related and similar topics or data that may contradict that position. Cherry-picking may be committed intentionally or unintentionally, but stillbirths the same results. History is not entirely exceptional, and nor is it wholly evil. And to not attempt to remain a centrist in these matters does a disservice to the historical community. In short, there is a current trend to politize American history as either American exceptionalism or a country founded solely on oppression. The truth is, both are right.

HIGHLIGHTS

LECTURES #023 Eli Whitney, Cookbooks, Bank Heists, and American Fitness (39:52) #024 Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings, Alexander Hamilton, and the Louisiana Purchase (41:19) #025 Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea, The Barbary Wars, and the Atlantic Slave Trade (39:07) #026: Tecumseh, Tippecanoe, and the War of 1812 (38:31) #027: Drinking, Singing, Bloodshed, and the Disenfranchised (32:56) READING My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Schweikart, Chapter 3 “Colonies No More, 1763-83”

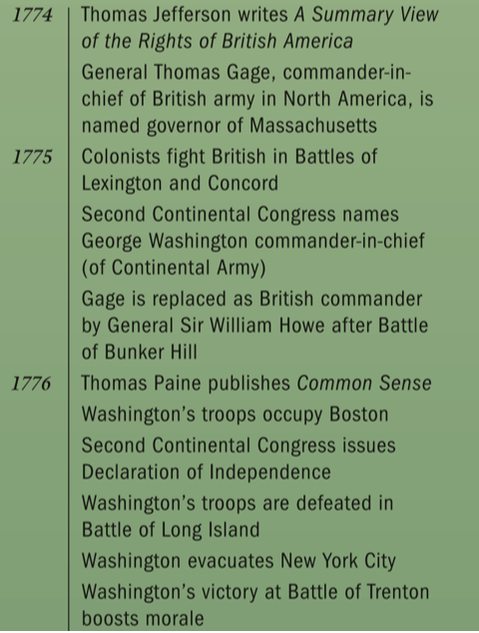

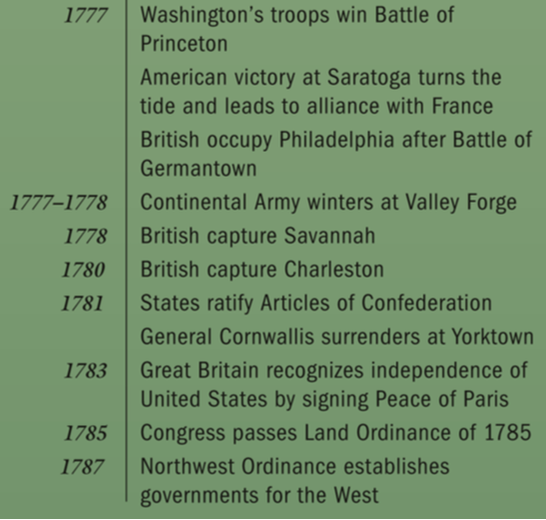

…Washington shuddered upon assuming command of the 30,000 troops surrounding Boston on July 3, 1775. He found fewer than fifty cannons and an ill-equipped “mixed multitude of people” comprising militia from New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. (Franklin actually suggested arming the military with bows and arrows! Although Washington theoretically commanded a total force of 300,000 scattered throughout the American colonies, in fact, he had a tiny actual combat force. Even the so-called regulars lacked discipline and equipment, despite bounties offered to attract soldiers and contributions from patriots to bolster the stores. Some willingly fought for what they saw as a righteous cause or for what they took as a threat to their homes and families, but others complained that they were “fed with promises” or clothed “with filthy rags.” Scarce materials drove up costs for the army and detracted from an efficient collection and distribution of goods, a malady that plagued the colonial armies until the end of the war. Prices paid for goods and labor in industry always exceeded those that the Continental Congress could offer—and beyond its ability to raise in taxation—making it especially difficult to obtain troops. Nevertheless, the regular units provided the only stable body under Washington’s command during the conflict—even as they came and went routinely because of the expiration of enlistment terms. Against the ragtag force mustered by the colonies, Great Britain pitted a military machine that had recently defeated the French and Spanish armies, supplied and transported by the largest, best trained, and most lavishly supplied navy on earth. Britain also benefited from numerous established forts and outposts; a colonial population that in part remained loyal; and the absence of immediate European rivals who could drain time, attention, or resources from the war in America. In addition, the British had an able war commander in the person of General William Howe and several experienced officers, such as Major General John Burgoyne and Lord Cornwallis. Nevertheless, English forces faced a number of serious, if unapparent, obstacles when it came to conducting campaigns in America. First and foremost, the British had to operate almost exclusively in hostile territory. That had not encumbered them during the French and Indian War, so, many officers reasoned; it would not present a problem in this conflict. But in the French and Indian War, the British had the support of most of the local population; whereas now, English movements were usually reported by patriots to American forces, and militias could harass them at will on the march. Second, command of the sea made little difference in the outcome of battles in interior areas. Worse, the vast barrier posed by the Atlantic made resupply and reinforcement by sea precarious, costly, and uncertain. Communications also hampered the British: submitting a question to the high command in England might entail a three-month turnaround time, contingent upon good weather. Third, no single port city offered a strategic center from which British forces could deploy. At one time the British had six armies in the colonies, yet they never managed to bring their forces together in a single, overwhelming campaign. They had to conduct operations through a wide expanse of territory, along a number of fronts involving seasonal changes from snow in New Hampshire to torrid heat in the Carolinas, all the while searching for rebels who disappeared into mountains, forests, or local towns. Fourth, British officers, though capable in European-style war, never adapted to fighting a frontier rebellion against another western-style army that had already adapted to the new battlefield. Competent leaders such as Howe made critical mistakes, while less talented officers like Burgoyne bungled completely. At the same time, Washington slowly developed aggressive officers like Nathaniel Greene, Ethan Allen, and (before his traitorous actions) Benedict Arnold. Fifth, England hoped that the Iroquois would join them as allies, and that, conversely, the colonists would be deprived of any assistance from the European powers. Both hopes were dashed. The Iroquois Confederacy declared neutrality in 1776, and many other tribes agreed to neutrality soon thereafter as a result of efforts by Washington’s able emissaries to the Indians. A few tribes fought for the British, particularly the Seneca and Cayuga, but two of the Iroquois Confederacy tribes actively supported the Americans and the Onondaga divided their loyalties. As for keeping the European nations out, the British succeeded in officially isolating America only for a short time before scores of European freedom fighters poured into the colonies. Casimir Pulaski, of Poland, and the Marquis de Lafayette, of France, made exemplary contributions; Thaddeus Kosciusko, another Pole, organized the defenses of Saratoga and West Point; and Baron von Steuben, a Prussian captain, drilled the troops at Valley Forge, receiving an informal promotion from Benjamin Franklin to general. Von Steuben’s presence underscored a reality that England had overlooked in the conflict— namely, that this would not be a battle against common natives who happened to be well armed. Quite the contrary, it would pit Europeans against their own. British success in overcoming native forces had been achieved by discipline, drill, and most of all the willingness of essentially free men to submit to military structures and utilize European close-order, mass-fire techniques. In America, however, the British armies encountered Continentals who fought with the same discipline and drill as they did, and who were as immersed in the same rights-of-Englishmen ideology that the British soldiers themselves had grown up with. It is thus a mistake to view Lexington and Concord, with their pitiable shot-to-kill ratio, as constituting the style of the war. Rather, Saratoga and Cowpens reflected the essence of massed formations and shock combat, with the victor usually enjoying the better ground or generalship. Worth noting also is the fact that Washington’s first genuine victory came over mercenary troops at Trenton, not over English redcoats, though that too would come. Even that instance underscored the superiority of free soldiers over indentured troops of any kind. Sixth, Great Britain’s commanders in the field each operated independently, and each from a distance of several thousand miles from their true command center, Whitehall. No British officer in the American colonies had authority over the entire effort, and ministerial interventions often reflected not only the woefully outdated appraisals of the situation—because of the delay in reporting intelligence—but also the internal politics that afflicted the British army until well after the Crimean War. Finally, of course, France decisively entered the fray in 1778, sensing that, in fact, the young nation might actually survive, and offering the French a means to weaken Britain by slicing away the North American colonies from her control, and providing sweet revenge for France’s humiliating defeat in the Seven Years’ War. The French fleet under Admiral Françoise Joseph de Grasse lured away the Royal Navy, which secured Cornwallis’s flanks at Yorktown, winning at Sandy Hook one of the few great French naval victories over England. Without the protection of the navy’s guns, Yorktown fell. There is little question that the weight of the French forces tipped the balance in favor of the Americans, but even had France stood aside, the British proved incapable of pinning down Washington’s army, and despite several victories had not broken the will of the colonists…

KEY TERMS

Eli Whitney American Cookery Alien and Sedition Acts The First Bank Heist National Period of Fitness Sally Hemings Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr The Burr Conspiracy Louisiana Purchase Lewis and Clark Sacagawea The Barbary War Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Tecumseh The Battle of Tippecanoe The War of 1812 The Siege of Detroit Ben Ali 19th Century Alcohol The Star Spangled Banner The Battle New Orleans American School for the Deaf The Civilization Fund Act ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #7

Crash Course is an educational YouTube channel started by the Green brothers, Hank Green and John Green. Originally, John and Hank presented humanities and science courses to viewers, respectively, although the series has since expanded to incorporate courses by an additional host. Watch this short video and please answer the following question with a two-paragraph minimum:

What are some major similarities between the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed