HST 150 Module #1

The Shot Callers (3300 BCE - 1438 CE)

Welcome to HST 150! This is the first learning module examining early civilizations in world history. Studying empires in world history is essential for several reasons. First and foremost, empires have played a significant role in shaping the world we live in today. Many of the political, economic, and cultural systems in place today have roots in past empires. Examining empires also allows us to understand better the histories and cultures of the various peoples and societies affected by these empires. By looking at how empires impacted different parts of the world, we can gain a deeper understanding of the forces that have shaped the world's diverse cultures. Also, studying empires can help us better understand imperialism and colonialism's causes and consequences. This can provide valuable insight into how power and resources have been distributed throughout history and how different groups interact. Overall, examining empires in world history allows us to understand better the complexity of the world's past and how it has shaped the world we live in today.

Welcome to HST 150! This is the first learning module examining early civilizations in world history. Studying empires in world history is essential for several reasons. First and foremost, empires have played a significant role in shaping the world we live in today. Many of the political, economic, and cultural systems in place today have roots in past empires. Examining empires also allows us to understand better the histories and cultures of the various peoples and societies affected by these empires. By looking at how empires impacted different parts of the world, we can gain a deeper understanding of the forces that have shaped the world's diverse cultures. Also, studying empires can help us better understand imperialism and colonialism's causes and consequences. This can provide valuable insight into how power and resources have been distributed throughout history and how different groups interact. Overall, examining empires in world history allows us to understand better the complexity of the world's past and how it has shaped the world we live in today.

#1 Historians are Detectives

We need to mention rule #1 for understanding history: Historians are detectives. Much like Batman or Sherlock Holmes, historian look at the crime scene (in this case, the historical event) look for clues (in this case, books or archaeological sites), interview witnesses (in this case, secondary or primary sources) and interpret the findings to determine what happened. Much like an actual crime scene, the investigator must rely on what they have in front of them. Missing pieces always happen, but it's the goal of the historian to fill in the blank spaces with what his or her 'gut" tells them. Or they go to their utility belt of previous knowledge to help determine the most likely outcomes. This becomes rather difficult the further we get from the time frame of the crime, or what is referred to as a "cold case." Scents get thrown off; memory gets muddled. The picture becomes murkier as time slips from our grasp.

In a 2022 Observer article, writer Rory Carroll dives into Irish historian Tom Reilly. Reilly has been ridiculed, condemned, and strong-armed with death for waging a one-person crusade to rehabilitate Oliver Cromwell, the most prominent evildoer in Ireland's history. He has spent three decades trying to persuade his companions that Oliver Cromwell, the 17th-century English conqueror, was moral, honorable, and not a murderer. For those uninitiated, Cromwell was an English politician and military officer widely considered one of the most crucial politicians in English history. He came to stature during the 1640s, first as a senior army commander and then as a politician. Cromwell stays extremely contentious in Britain and Ireland due to his use of the military first to obtain, then maintain, political power and the savagery of his 1649 Irish campaign.

The lengthy, bloodstained method of occupying Ireland generated – directly or indirectly – the demises of such a vast section of the population that the word 'genocide' has even been used. It altered the course of history, leading to stormy ties with England for centuries. Reilly, who has spent 30 years reviewing primary sources, does not deny the widespread bloodshed or infamous components. Nevertheless, he says Cromwell's troops spared civilians and exterminated solely enemy combatants – some in battle, most after they had yielded, a cruel policy but in keeping with the era's code of war. Reilly says Irish history books conflate executed soldiers with "inhabitants," suggesting they were civilians.

Where does he come from with this authority? A lot of detective work is implicated in this century-year-old cold case. Pulling on new material and salvaged original texts, Reilly can re-establish Cromwell's (what he calls) "authentic voice." Is he wrong? Is he right? That is not the pertinent question here. What we should be asking is, does he have enough evidence to create a case? Why do I mention this? Remember that as we dive into the world of "pre-history" we don't have all the answers, and never will.

Comparisons between historians and detectives are not unfounded. The work of both professions requires sifting through fragments of information to construct a coherent and truthful narrative. Historians, just like detectives, are tasked with examining past events, interpreting the clues that remain, and weaving them together to create a rich tapestry of history. But the task of the historian goes beyond mere fact-finding. Instead, it involves interpreting and analyzing evidence to understand the complexities of human experience. History is not simply a collection of dates and names; it is a story of people and their struggles, triumphs, and tragedies. A skilled historian can excavate the hidden stories of those silenced or ignored by dominant narratives, revealing the nuances of history that are often overlooked.

In our current world, where misinformation and half-truths run rampant, studying history in this way is more critical than ever. Only by understanding the past can we comprehend the present and shape the future. As Howard Zinn famously noted, "You can't be neutral on a moving train." By studying history critically, we can recognize the biases and agendas that shape our understanding of the world and work towards a more just and equitable future. Do you know how detectives and historians are alike? They both have to gather evidence that it's going out of style. Detectives collect all kinds of clues from crime scenes and interviews with witnesses, trying to build a case against some poor sap. Historians, they're similar, you know. They gather evidence from here, there, and everywhere to assemble the past. They use primary sources like diaries, letters, and official records and secondary sources like smarty-pants articles and books. But let me tell you, they can't just take everything at face value. They must give every source a good once-over, ensuring it's credible and relevant to their research.

If one thing angers my adrenaline, it's uncovering the truth behind a scandal. Take the Watergate scandal in the '70s, for example. Historians and journalists had their work cut out for them as they sifted through a mountain of evidence to unravel the mess at the Democratic National Committee headquarters. The stakes were high, and the mystery was thick. These folks relied on every tool in the toolbox: confidential sources, government documents, and witness testimony all played a role in piecing together the twisted tale of political intrigue that led to President Richard Nixon's downfall. And let me tell you, and it was a challenging feat. Every detail had to be carefully evaluated, and every scrap of evidence scrutinized.

But in the end, these dedicated historians were able to construct a detailed and accurate account of what went down. It's the kind of work that makes my heart race and my palms sweat – the thrill of the chase, the satisfaction of uncovering the truth. There's nothing quite like it. Consider this: what do historians and detectives have in common? Sure, you might immediately think of their mutual love for trench coats and magnifying glasses, but there's more to it than that. Both professions are fundamentally tasked with interpreting evidence, but the key difference lies in the period. Detectives use their expertise in criminal behavior to decipher the evidence they've gathered and make calculated judgments. On the other hand, historians utilize their knowledge of past events to interpret evidence and arrive at informed conclusions about the historical record. It's not just about the facts themselves; it's about what those facts can tell us about the human experience across time.

We're talking about the Big One, the War to End All Wars, the OG World War, baby. Historians have been digging deep, sifting through diplomatic chit-chat, military intel, and the innermost thoughts of the players involved, all in an attempt to crack the case on what sparked this global conflagration. Some folks say it was all about the Krauts and the Austrians getting too big for their britches, flexing their muscles, and throwing their weight around like a few drunken bar brawlers. But others take a step back, see the bigger picture, and say no; this thing was brewing for a long time, thanks to the tangled web of alliances and the never-ending arms race.

And how do these historians make sense of it all? Using their deep knowledge of the past to interpret the evidence to uncover the hidden motivations and the complex dynamics at play. It isn't always pretty, and it sure ain't simple, but in the end, we get a more nuanced understanding of how the world turned upside down. See, it isn't just about knowing what happened in the past; it's about seeing how it all ties into the present, giving us some damn context for what's happening now. When we look back at what went down, we can start to get a grip on where all these problems we're dealing with today came from and what we can do to fix them.

Take the Civil Rights Movement, for instance. We all know it was a game-changer, a moment that shook the very foundations of America. But it isn't just some old news. It's still relevant as hell today. By digging into that history, we can start to see the roots of the ongoing fight for racial justice in this country. And that isn't just some academic exercise. It's about figuring out how we can move forward and make things right. In examining history through this lens, we uncover a crucial benefit - the cultivation of critical thinking abilities. Discerning evidence and formulating informed interpretations foster a set of proficiencies that prove invaluable across various fields. Amongst these proficiencies lie the aptitude to scrutinize sources, detect partiality, and arrive at well-reasoned resolutions despite insufficiencies in information.

Delving into history aids us in safeguarding our cultural lineage. By chronicling yesteryears, we guarantee that future cohorts shall possess a copious and eclectic narrative of human existence. If not for historians sleuthing away to unearth and construe evidence, much of this saga would fade into obscurity. Like a gumshoe, a historian must gather and decipher clues to create a coherent narrative of bygone eras. It's a painstaking and often perplexing task that ultimately illuminates our present-day reality. Through the lens of history, we can hone our critical thinking skills and gain a deeper appreciation for our cultural heritage. We must preserve our ancestors' stories, triumphs, and missteps so that future generations may learn from their experiences.

But don't worry- I'm Batman.

RUNDOWN

Works Cited

"Watergate Scandal." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., n.d. Web. 03 May 2023.

"World War I." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., n.d. Web. 03 May 2023.

Davidson, James West, and Mark Hamilton Lytle. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010. Print.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Empire, 1875-1914. New York: Vintage, 1989. Print.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005. Print.

We need to mention rule #1 for understanding history: Historians are detectives. Much like Batman or Sherlock Holmes, historian look at the crime scene (in this case, the historical event) look for clues (in this case, books or archaeological sites), interview witnesses (in this case, secondary or primary sources) and interpret the findings to determine what happened. Much like an actual crime scene, the investigator must rely on what they have in front of them. Missing pieces always happen, but it's the goal of the historian to fill in the blank spaces with what his or her 'gut" tells them. Or they go to their utility belt of previous knowledge to help determine the most likely outcomes. This becomes rather difficult the further we get from the time frame of the crime, or what is referred to as a "cold case." Scents get thrown off; memory gets muddled. The picture becomes murkier as time slips from our grasp.

In a 2022 Observer article, writer Rory Carroll dives into Irish historian Tom Reilly. Reilly has been ridiculed, condemned, and strong-armed with death for waging a one-person crusade to rehabilitate Oliver Cromwell, the most prominent evildoer in Ireland's history. He has spent three decades trying to persuade his companions that Oliver Cromwell, the 17th-century English conqueror, was moral, honorable, and not a murderer. For those uninitiated, Cromwell was an English politician and military officer widely considered one of the most crucial politicians in English history. He came to stature during the 1640s, first as a senior army commander and then as a politician. Cromwell stays extremely contentious in Britain and Ireland due to his use of the military first to obtain, then maintain, political power and the savagery of his 1649 Irish campaign.

The lengthy, bloodstained method of occupying Ireland generated – directly or indirectly – the demises of such a vast section of the population that the word 'genocide' has even been used. It altered the course of history, leading to stormy ties with England for centuries. Reilly, who has spent 30 years reviewing primary sources, does not deny the widespread bloodshed or infamous components. Nevertheless, he says Cromwell's troops spared civilians and exterminated solely enemy combatants – some in battle, most after they had yielded, a cruel policy but in keeping with the era's code of war. Reilly says Irish history books conflate executed soldiers with "inhabitants," suggesting they were civilians.

Where does he come from with this authority? A lot of detective work is implicated in this century-year-old cold case. Pulling on new material and salvaged original texts, Reilly can re-establish Cromwell's (what he calls) "authentic voice." Is he wrong? Is he right? That is not the pertinent question here. What we should be asking is, does he have enough evidence to create a case? Why do I mention this? Remember that as we dive into the world of "pre-history" we don't have all the answers, and never will.

Comparisons between historians and detectives are not unfounded. The work of both professions requires sifting through fragments of information to construct a coherent and truthful narrative. Historians, just like detectives, are tasked with examining past events, interpreting the clues that remain, and weaving them together to create a rich tapestry of history. But the task of the historian goes beyond mere fact-finding. Instead, it involves interpreting and analyzing evidence to understand the complexities of human experience. History is not simply a collection of dates and names; it is a story of people and their struggles, triumphs, and tragedies. A skilled historian can excavate the hidden stories of those silenced or ignored by dominant narratives, revealing the nuances of history that are often overlooked.

In our current world, where misinformation and half-truths run rampant, studying history in this way is more critical than ever. Only by understanding the past can we comprehend the present and shape the future. As Howard Zinn famously noted, "You can't be neutral on a moving train." By studying history critically, we can recognize the biases and agendas that shape our understanding of the world and work towards a more just and equitable future. Do you know how detectives and historians are alike? They both have to gather evidence that it's going out of style. Detectives collect all kinds of clues from crime scenes and interviews with witnesses, trying to build a case against some poor sap. Historians, they're similar, you know. They gather evidence from here, there, and everywhere to assemble the past. They use primary sources like diaries, letters, and official records and secondary sources like smarty-pants articles and books. But let me tell you, they can't just take everything at face value. They must give every source a good once-over, ensuring it's credible and relevant to their research.

If one thing angers my adrenaline, it's uncovering the truth behind a scandal. Take the Watergate scandal in the '70s, for example. Historians and journalists had their work cut out for them as they sifted through a mountain of evidence to unravel the mess at the Democratic National Committee headquarters. The stakes were high, and the mystery was thick. These folks relied on every tool in the toolbox: confidential sources, government documents, and witness testimony all played a role in piecing together the twisted tale of political intrigue that led to President Richard Nixon's downfall. And let me tell you, and it was a challenging feat. Every detail had to be carefully evaluated, and every scrap of evidence scrutinized.

But in the end, these dedicated historians were able to construct a detailed and accurate account of what went down. It's the kind of work that makes my heart race and my palms sweat – the thrill of the chase, the satisfaction of uncovering the truth. There's nothing quite like it. Consider this: what do historians and detectives have in common? Sure, you might immediately think of their mutual love for trench coats and magnifying glasses, but there's more to it than that. Both professions are fundamentally tasked with interpreting evidence, but the key difference lies in the period. Detectives use their expertise in criminal behavior to decipher the evidence they've gathered and make calculated judgments. On the other hand, historians utilize their knowledge of past events to interpret evidence and arrive at informed conclusions about the historical record. It's not just about the facts themselves; it's about what those facts can tell us about the human experience across time.

We're talking about the Big One, the War to End All Wars, the OG World War, baby. Historians have been digging deep, sifting through diplomatic chit-chat, military intel, and the innermost thoughts of the players involved, all in an attempt to crack the case on what sparked this global conflagration. Some folks say it was all about the Krauts and the Austrians getting too big for their britches, flexing their muscles, and throwing their weight around like a few drunken bar brawlers. But others take a step back, see the bigger picture, and say no; this thing was brewing for a long time, thanks to the tangled web of alliances and the never-ending arms race.

And how do these historians make sense of it all? Using their deep knowledge of the past to interpret the evidence to uncover the hidden motivations and the complex dynamics at play. It isn't always pretty, and it sure ain't simple, but in the end, we get a more nuanced understanding of how the world turned upside down. See, it isn't just about knowing what happened in the past; it's about seeing how it all ties into the present, giving us some damn context for what's happening now. When we look back at what went down, we can start to get a grip on where all these problems we're dealing with today came from and what we can do to fix them.

Take the Civil Rights Movement, for instance. We all know it was a game-changer, a moment that shook the very foundations of America. But it isn't just some old news. It's still relevant as hell today. By digging into that history, we can start to see the roots of the ongoing fight for racial justice in this country. And that isn't just some academic exercise. It's about figuring out how we can move forward and make things right. In examining history through this lens, we uncover a crucial benefit - the cultivation of critical thinking abilities. Discerning evidence and formulating informed interpretations foster a set of proficiencies that prove invaluable across various fields. Amongst these proficiencies lie the aptitude to scrutinize sources, detect partiality, and arrive at well-reasoned resolutions despite insufficiencies in information.

Delving into history aids us in safeguarding our cultural lineage. By chronicling yesteryears, we guarantee that future cohorts shall possess a copious and eclectic narrative of human existence. If not for historians sleuthing away to unearth and construe evidence, much of this saga would fade into obscurity. Like a gumshoe, a historian must gather and decipher clues to create a coherent narrative of bygone eras. It's a painstaking and often perplexing task that ultimately illuminates our present-day reality. Through the lens of history, we can hone our critical thinking skills and gain a deeper appreciation for our cultural heritage. We must preserve our ancestors' stories, triumphs, and missteps so that future generations may learn from their experiences.

But don't worry- I'm Batman.

RUNDOWN

- Historians are like detectives; they use clues to understand past events and interpret findings to determine what happened.

- Irish historian Tom Reilly spent 30 years trying to rehabilitate Oliver Cromwell, a controversial figure in Irish history, by reviewing primary sources and establishing his "authentic voice."

- Reilly claims that Irish history books wrongly suggest that Cromwell's troops killed civilians while they only killed enemy combatants who had yielded.

- Historians are essential because they excavate hidden stories and understand the complexities of human experience, helping us to shape the future by learning from the past.

- Historians and detectives gather evidence to build a case, and historians must evaluate sources to ensure they are credible and relevant.

- Historians and journalists worked together to uncover the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, using confidential sources, government documents, and witness testimony to piece together a twisted tale of political intrigue.

Works Cited

"Watergate Scandal." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., n.d. Web. 03 May 2023.

"World War I." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., n.d. Web. 03 May 2023.

Davidson, James West, and Mark Hamilton Lytle. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010. Print.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Empire, 1875-1914. New York: Vintage, 1989. Print.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005. Print.

STATE OF THE WORLD

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- COMING SOON

READING

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Bentley, Jerry. Traditions & Encounter Volume 1 from Beginning to 1500, 7th ed.: McGraw Hill, 2021 .

Jerry H. Bentley was a historian and academic who specialized in world history, with a focus on cultural and economic exchange, comparative history, and the study of empires. He was a professor at the University of Hawaii and served as the President of the American Historical Association. Bentley wrote several books on world history and globalization, including "Old World Encounters" and he made significant contributions to the field. He passed away in 2014.

- Bentley, Chapter 1: Early Human History

- Bentley, Chapter 2: The Emergence of Complex Societies in Southwest Asia and Encounters with Indo-European-Speaking Peoples

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Bentley, Jerry. Traditions & Encounter Volume 1 from Beginning to 1500, 7th ed.: McGraw Hill, 2021 .

Jerry H. Bentley was a historian and academic who specialized in world history, with a focus on cultural and economic exchange, comparative history, and the study of empires. He was a professor at the University of Hawaii and served as the President of the American Historical Association. Bentley wrote several books on world history and globalization, including "Old World Encounters" and he made significant contributions to the field. He passed away in 2014.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

...Empire abroad requires repression at home. The history of the Roman Empire is a history of the repression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad. The history of the British Empire is a history of the suppression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad. The history of the United States is a history of the suppression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad....

"Empires, by their very nature, are based on exploitation and oppression. The Roman Empire was based on the exploitation of conquered peoples and the oppression of the poor. The British Empire was based on the exploitation of conquered peoples and the oppression of the poor. The United States, like all empires, has always been interested in its own expansion, its own profits, and therefore, in the suppression of independent movements elsewhere...

...The United States, like all empires, has always been interested in its own expansion, its own profits, and therefore, in the suppression of independent movements elsewhere. It is not only the Roman Empire, the British Empire, and the Spanish Empire that have been interested in this; it is the history of empires in general...

...Empire abroad requires repression at home. The history of the Roman Empire is a history of the repression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad. The history of the British Empire is a history of the suppression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad. The history of the United States is a history of the suppression of people at home in order to conquer people abroad....

"Empires, by their very nature, are based on exploitation and oppression. The Roman Empire was based on the exploitation of conquered peoples and the oppression of the poor. The British Empire was based on the exploitation of conquered peoples and the oppression of the poor. The United States, like all empires, has always been interested in its own expansion, its own profits, and therefore, in the suppression of independent movements elsewhere...

...The United States, like all empires, has always been interested in its own expansion, its own profits, and therefore, in the suppression of independent movements elsewhere. It is not only the Roman Empire, the British Empire, and the Spanish Empire that have been interested in this; it is the history of empires in general...

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

...When celebrating triumphs—whether over inflation, interest rates, unemployment, or communism—Reagan used “we” or “together.” When calling on fellow citizens for support, he expressed his points in clear examples and heartwarming stories. An example, he said, was always better than a sermon. No matter what he or government did, to Reagan it was always the people of the nation who made the country grow and prosper. Most important, he did not hesitate to speak that he thought was the truth, calling the Soviet Union the “evil empire,” a term that immediately struck a note with millions of Star Wars fans and conjuring up the image of a decrepit Soviet leader as the “emperor” bent on destroying the Galactic Republic (America). Once, preparing to make a statement about the Soviet Union, Reagan did not realize a microphone was left on, and he joked to a friend, “The bombing begins in five minutes.” Horrified reporters scurried about in panic, certain that this gunslinger-cowboy president was serious...

...The “evil empire” speech paved the way for one of the most momentous events of the post–World War II era. On March 23, 1983, in a television address, after revealing previously classified photographs of new Soviet weapons and installations in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Grenada, and reviewing the Soviet advantage in heavy missiles, Reagan surprised even many of his supporters by calling for a massive national commitment to build a defense against ballistic missiles. He urged scientists and engineers to use any and all new technologies, including (but not limited to) laser beam weapons in space...

...When celebrating triumphs—whether over inflation, interest rates, unemployment, or communism—Reagan used “we” or “together.” When calling on fellow citizens for support, he expressed his points in clear examples and heartwarming stories. An example, he said, was always better than a sermon. No matter what he or government did, to Reagan it was always the people of the nation who made the country grow and prosper. Most important, he did not hesitate to speak that he thought was the truth, calling the Soviet Union the “evil empire,” a term that immediately struck a note with millions of Star Wars fans and conjuring up the image of a decrepit Soviet leader as the “emperor” bent on destroying the Galactic Republic (America). Once, preparing to make a statement about the Soviet Union, Reagan did not realize a microphone was left on, and he joked to a friend, “The bombing begins in five minutes.” Horrified reporters scurried about in panic, certain that this gunslinger-cowboy president was serious...

...The “evil empire” speech paved the way for one of the most momentous events of the post–World War II era. On March 23, 1983, in a television address, after revealing previously classified photographs of new Soviet weapons and installations in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Grenada, and reviewing the Soviet advantage in heavy missiles, Reagan surprised even many of his supporters by calling for a massive national commitment to build a defense against ballistic missiles. He urged scientists and engineers to use any and all new technologies, including (but not limited to) laser beam weapons in space...

“...the fight that political philosophers have always identified as the central conflict in human history: that between the individual and society. Thus far, scholars have shown little interest in finding this conflict in American history...”

― Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

What Does Professor Lancaster Think?

Political philosophers have long recognized the fundamental conflict between the individual and society as a central theme in human history. However, few scholars have studied this conflict in the context of American history.

Empires require the suppression of people within their borders in order to conquer other peoples and territories. Throughout history, empires have been based on exploitation and oppression, and have sought their own expansion and profit at the expense of other nations. The United States, as an empire, has also pursued these goals. Ronald Reagan used heartwarming stories and clear examples to appeal to the American people and gain their support. He famously referred to the Soviet Union as the "evil empire" and called for a massive national commitment to build a defense against ballistic missiles, including the use of new technologies such as laser beam weapons in space.

Empires can bring economic benefits to both the imperial power and the conquered territories. For example, the British Empire was known for its trade networks, which brought wealth and prosperity to both Britain and the colonies it controlled. Empires can also provide political stability to conquered territories, as they often get a sense of order and the rule of law. This can be particularly beneficial in regions prone to conflict or with a history of weak governance. Empires can also facilitate cultural exchange between different groups, as they often bring people from diverse backgrounds together. This can lead to the spread of new ideas, technologies, and cultural practices. Some argue that empires can also play a role in modernizing and improving the infrastructure of conquered territories. For example, the British Empire was known for building roads, railroads, and other infrastructure projects in the territories it controlled.

However, it is essential to note that these arguments in favor of empires are often contested, and there are also many criticisms of empires and their impact on history.

Empires have often been criticized for exploiting the resources and labor of the territories they control and oppressing the people living in those territories. This can lead to social and economic inequalities and human rights abuses. Empires often exert control over conquered territories, leading to the loss of sovereignty for the people living in those territories. This can result in a lack of self-determination and the inability to govern themselves. Empires may also seek to assimilate conquered peoples into their own culture, often imposing their language, religion, and other cultural practices on the people living in the conquered territories. This can lead to the loss of cultural identity and traditions. Empires may also engage in activities that can lead to environmental destruction in their control regions, such as resource extraction and deforestation. Empires often face resistance and conflict from the people living in the territories they control, as they may resist imperial rule and strive for independence. This can lead to violent conflict and unrest.

Overall, empires have often been criticized for their negative impact on the societies and cultures of the territories they control and their role in shaping global power dynamics and contributing to inequality and injustice.

Political philosophers have long recognized the fundamental conflict between the individual and society as a central theme in human history. However, few scholars have studied this conflict in the context of American history.

Empires require the suppression of people within their borders in order to conquer other peoples and territories. Throughout history, empires have been based on exploitation and oppression, and have sought their own expansion and profit at the expense of other nations. The United States, as an empire, has also pursued these goals. Ronald Reagan used heartwarming stories and clear examples to appeal to the American people and gain their support. He famously referred to the Soviet Union as the "evil empire" and called for a massive national commitment to build a defense against ballistic missiles, including the use of new technologies such as laser beam weapons in space.

Empires can bring economic benefits to both the imperial power and the conquered territories. For example, the British Empire was known for its trade networks, which brought wealth and prosperity to both Britain and the colonies it controlled. Empires can also provide political stability to conquered territories, as they often get a sense of order and the rule of law. This can be particularly beneficial in regions prone to conflict or with a history of weak governance. Empires can also facilitate cultural exchange between different groups, as they often bring people from diverse backgrounds together. This can lead to the spread of new ideas, technologies, and cultural practices. Some argue that empires can also play a role in modernizing and improving the infrastructure of conquered territories. For example, the British Empire was known for building roads, railroads, and other infrastructure projects in the territories it controlled.

However, it is essential to note that these arguments in favor of empires are often contested, and there are also many criticisms of empires and their impact on history.

Empires have often been criticized for exploiting the resources and labor of the territories they control and oppressing the people living in those territories. This can lead to social and economic inequalities and human rights abuses. Empires often exert control over conquered territories, leading to the loss of sovereignty for the people living in those territories. This can result in a lack of self-determination and the inability to govern themselves. Empires may also seek to assimilate conquered peoples into their own culture, often imposing their language, religion, and other cultural practices on the people living in the conquered territories. This can lead to the loss of cultural identity and traditions. Empires may also engage in activities that can lead to environmental destruction in their control regions, such as resource extraction and deforestation. Empires often face resistance and conflict from the people living in the territories they control, as they may resist imperial rule and strive for independence. This can lead to violent conflict and unrest.

Overall, empires have often been criticized for their negative impact on the societies and cultures of the territories they control and their role in shaping global power dynamics and contributing to inequality and injustice.

KEY TERMS

ASSIGNMENTS

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #1

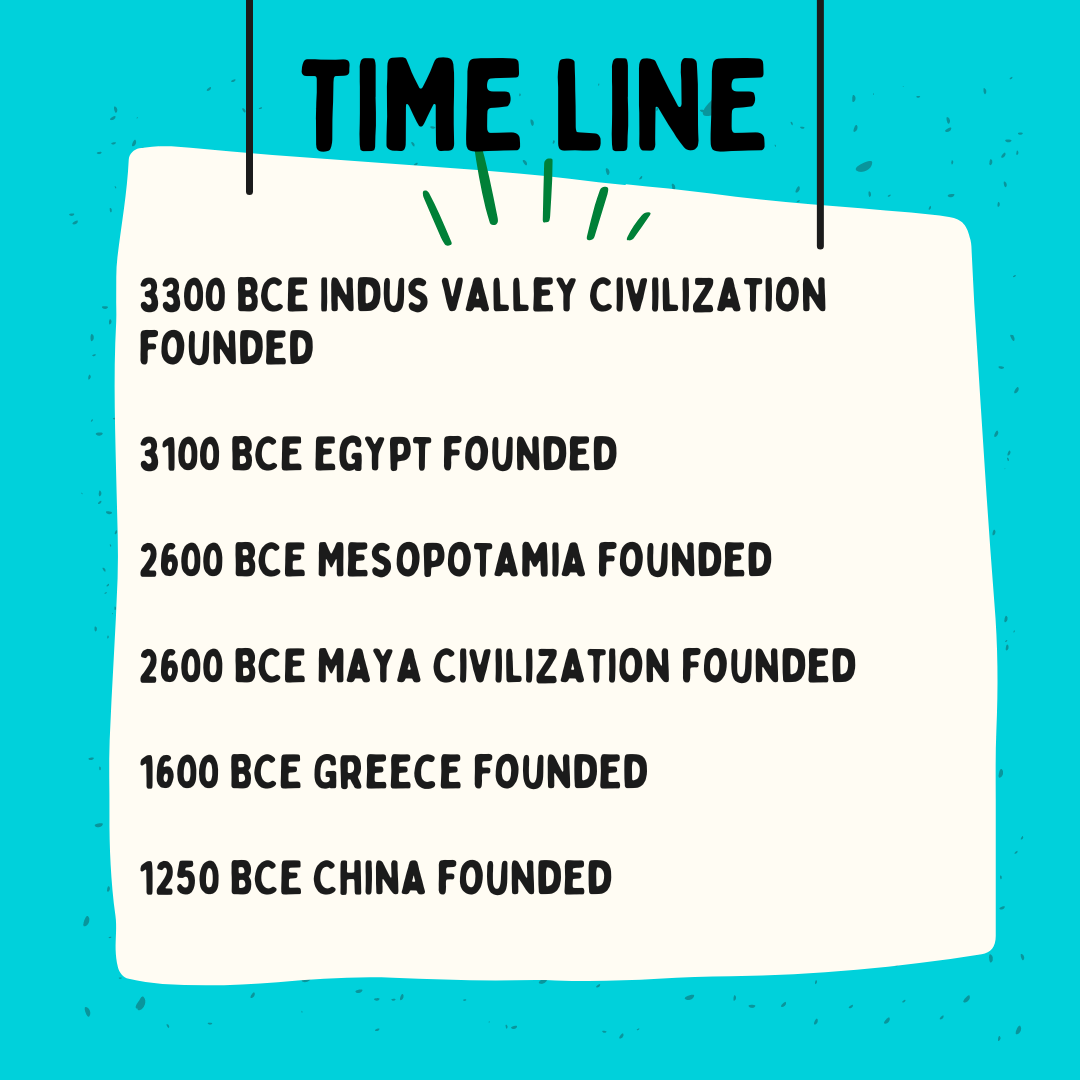

- 3300 BCE Indus Valley Civilization

- 3100 BCE Egypt

- 2600 BCE Mesopotamia

- 2600 BCE Maya Civilization

- 1600 BCE Greece

- 1250 BCE China

- 753 BCE Rome

- 550 BCE Persia

- 400 BCE Kingdom of Aksum

- 300 CE Kingdom of Ghana

- 400 CE Byzantine Empire

- 800 CE Holy Roman Empire

- 1000 CE Kingdom of Songhai

- 1206 CE Mongol Empire

- 1220 CE Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe

- 1235 CE Kingdom of Mali

- 1299 CE Ottoman Empire

- 1428 CE Aztec Empire

- 1438 CE Inca Empire

ASSIGNMENTS

- Forum Discussion #1

- Forum Discussion #2

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #1

This first week I would like to take it easy, and get to know you better, please answer the following question with a one paragraph minimum:

What do you like about studying history? If you don't like history, what do you think the root cause is? Remember that you will be required to reply to at least two of your classmates.

Forum Discussion #2

History is an American cable network owned by A&E Networks, a joint venture between Hearst Communications and Disney's General Entertainment Content division. Initially, the channel aired history-based documentaries and social and science programming. However, in the late 2000s, it shifted toward reality TV shows. Many experts, including scientists, historians, and skeptics, have criticized this change in content for featuring pseudo-documentaries and sensationalistic, unscientific investigative programming that is not supported by evidence.

Watch this video and answer the following question:

What do you like about studying history? If you don't like history, what do you think the root cause is? Remember that you will be required to reply to at least two of your classmates.

Forum Discussion #2

History is an American cable network owned by A&E Networks, a joint venture between Hearst Communications and Disney's General Entertainment Content division. Initially, the channel aired history-based documentaries and social and science programming. However, in the late 2000s, it shifted toward reality TV shows. Many experts, including scientists, historians, and skeptics, have criticized this change in content for featuring pseudo-documentaries and sensationalistic, unscientific investigative programming that is not supported by evidence.

Watch this video and answer the following question:

How did the legacies of empires shape the modern world, and what lessons can we learn from the successes and failures of these empires?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

LEGAL MUMBO JUMBO

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.