|

Module Four: Colonial Age Part 3 The British Empire (1754 CE - 1795 CE)

Welcome to HST 201 Module Four! We are looking at effects of British Empire on the North American landscape . I mentioned prior that the two ways to really know a culture was trough their food and their music. But there are other ways that are quite frankly a little more fun: sex and drugs. The things a culture does in private gives us another chapter of the book of history that most historians often skip writing. And perhaps this is selfish, but I just am not that interested in the dogmas of religion and politics. It seems that that we want to focus on historical figures and their grandiose policies and edicts rather than the what the everyday man or woman endured. So, our next rule of history: Don’t focus on the 1% of history. If you do, you will only be looking at essentially elite white men, and as we all know by now there are plenty of other stories to tell. Howard Zinn started this notion with bottom up history in his work, People’s History of the United States, and has since evolved into the “from the gutter up” lens of history coined by Thaddeus Russell in his work A Renegade’s History of the United States.

HIGHLIGHTS

LECTURES

READING

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Schweikart, Chapter 2 “Colonial Adolescence, 1707-63”

…Life in colonial America was as coarse as the physical environment in which it flourished, so much so that English visitors expressed shock at the extent to which emigrants had been transformed in the new world. Many Americans lived in one-room farmhouses, heated only by a Franklin stove, with clothes hung on wall pegs and few furnishings. “Father’s chair” was often the only genuine chair in a home, with children relegated to rough benches or to rugs thrown on the wooden floors. This rugged lifestyle was routinely misunderstood by visitors as “Indianization,” yet in most cases, the process was subtle. Trappers had already adopted moccasins, buckskins, and furs, and adapted Indian methods of hauling hides or goods over rough terrain with the travois, a triangular-shaped and easily constructed sled pulled by a single horse. Indians, likewise, adopted white tools, firearms, alcohol, and even accepted English religion, making the acculturation process entirely reciprocal. Non-Indians incorporated Indian words (especially proper names) into American English and adopted aspects of Indian material culture. They smoked tobacco, grew and ate squash and beans, dried venison into jerky, boiled lobsters and served them up with wild rice or potatoes on the side. British-Americans cleared heavily forested land by girdling trees, then slashing and burning the dead timber—practices picked up from the Indians, despite the myth of the ecologically friendly natives. Whites copied Indians in traveling via snowshoes, bullboat, and dugout canoe. And colonial Americans learned quickly—through harsh experience—how to fight like the Indians. Even while Indianizing their language, British colonists also adopted French, Spanish, German, Dutch, and African words from areas where those languages were spoken, creating still regional accents that evolved in New England and the southern tidewater. Environment also influenced accents, producing the flat, unmelodic, understated, and functional midland American drawl that European found incomprehensible. Americans prided themselves on innovative spellings, stripping the excess baggage off English words, exchanging “color” for “colour,” “labor” for “labour,” or otherwise respelled words in harder American syllables, as in “theater” for “theatre.” This new brand of English was so different that around the time of the American Revolution, a young New Englander named Noah Webster began work on a dictionary of American English, which he completed in 1830. Only a small number of colonial Americans went on to college (often in Great Britain), but increasing numbers studied at public and private elementary schools, raising the most literate population on earth. American’s literacy was widespread, but it was not deep or profound. Most folks read a little and not much more. In response, a new form of publishing arose to meet the demands of this vast, but minimally literate, populace: the newspaper. Early newspapers came in the form of broadsides, usually distributed and posted in the lobby of an inn or saloon where one of the more literate colonials would proceed to read a story aloud for the dining or drinking clientele. Others would chime in with editorial comments during the reading, making for a truly democratic and interactive forum.7Colonial newspapers contained a certain amount of local information about fires, public drunkenness, arrests, and political events, more closely resembling today’s National Enquirer than the New York Times. Americans’ fascination with light or practical reading meant that hardback books, treatises, and the classics—the mainstay of European booksellers—were replaced by cheaply bound tracts, pamphlets, almanacs, and magazines. Those Americans interested in political affairs displayed a hearty appetite for plainly written radical Whig political tracts that emphasized the legislative authority over that of an executive, and that touted the participation of free landholders in government. And, of course, the Bible was found in nearly every cottage. Democratization extended to the professions of law and medicine—subsequently, some would argue, deprofessionalizing them. Unlike British lawyers, who were formally trained in English courts and then compartmentalized into numerous specialties, American barristers learned on the job and engaged in general legal practices. The average American attorney served a brief, informal apprenticeship; bought three or four good law books (enough to fill two saddlebags, it was said); and then, literally, hung out his shingle. If he lacked legal skills and acumen, the free market would soon seal his demise. Unless schooled in Europe, colonial physicians and midwives learned on the job, with limited supervision. Once on their own they knew no specialization; surgery, pharmacy, midwifery, dentistry, spinal adjustment, folk medicine, and quackery were all characteristic of democratized professional medical practitioners flourishing in a free market. In each case, the professions reflected the American insistence that their tools—law medicine, literature—emphasize application over theory…

KEY TERMS

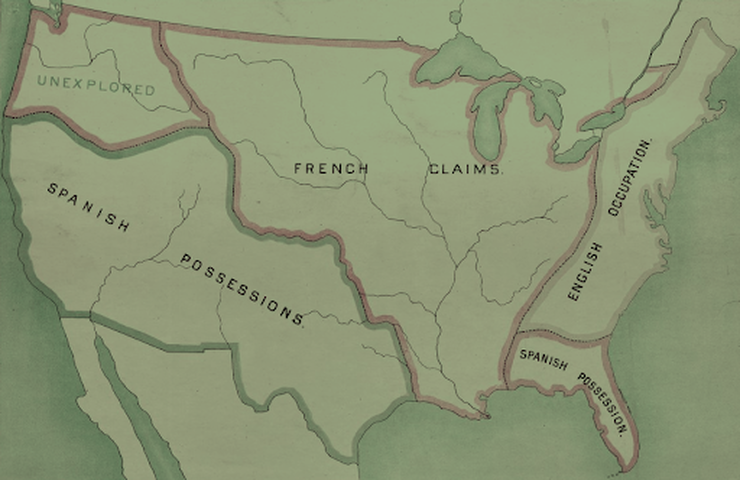

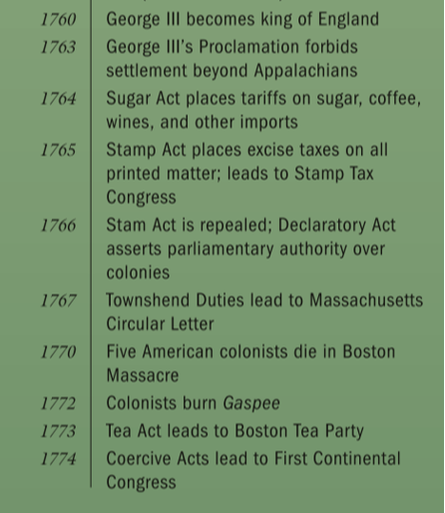

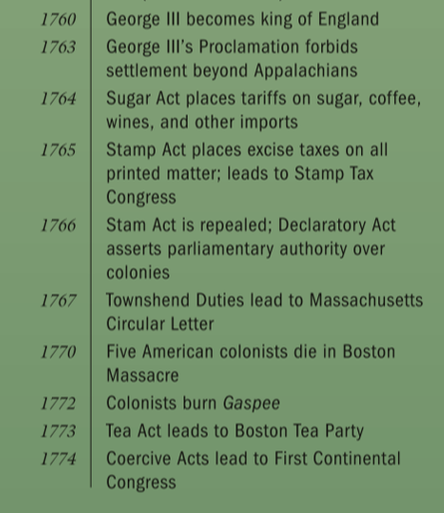

French and Indian War Fort Michilimackinac Proclamation Line of 1763 Pontiac's War Louisiana The Stamp Act The Townshend Acts Colonial Education The Boston Massacre Late Colonial Women Late Colonial Diet Greek Life Boston Tea Party Thomas Paine The American Revolution Smallpox Women in the Revolution The Physical Toll Latinos in the American Revolution African Americans in the Revolution Jews in the Revolution Muslims and the Revolution Sex and the Revolution The Fourth of July The Declaration of Independence Francis Marion

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #5

"Comedy is simply a funny way of being serious." - Peter Ustinov

For those who do not know, Drunk History is an American educational television comedy series produced by Comedy Central. In each episode, an inebriated narrator, who is played by a comedian joined by host Derek Waters, struggles to recount an event from history, while actors enact the narrator's anecdotes and lip sync the dialogue. Watch this short video and please answer the following question with a two-paragraph minimum: After hearing the “oral retelling” of George Washington's Continental Army and Baron von Steuben, decipher what is fact and fiction. How reliable is this source? What is recorded fact? What is embellished? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed