HST 202 Module #10

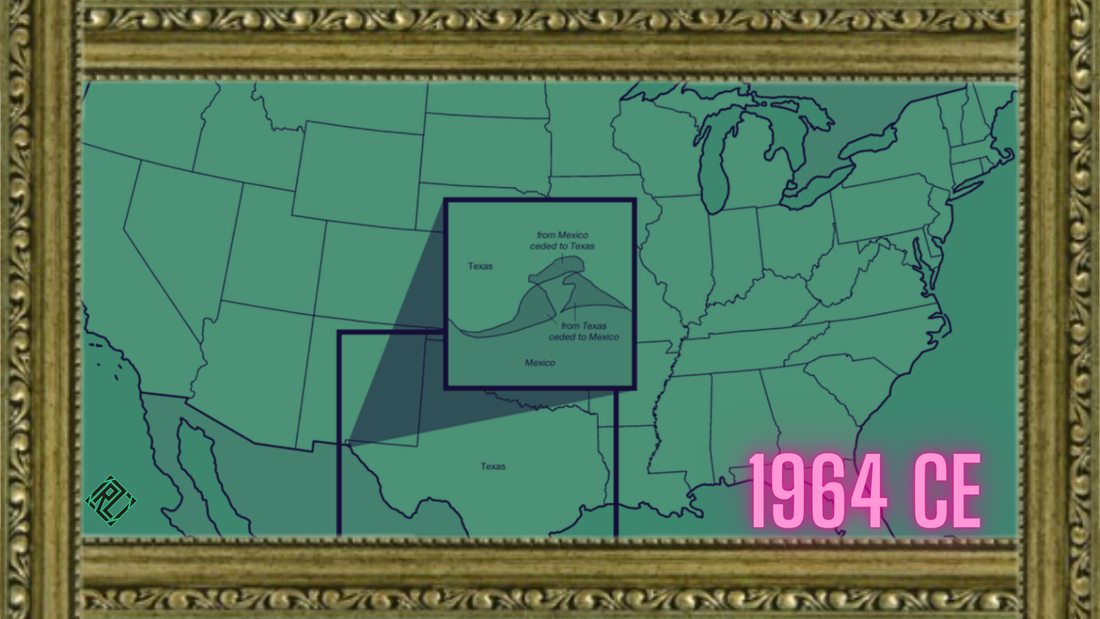

All Along the Watchtower (1964 CE - 1971 CE)

The swinging sixties and the groovy seventies were a time when America was like a mixed bag of social chaos, political pandemonium, and enough cultural upheaval to make your head spin faster than a DJ scratching a record. It was a period when the nation went through more identity crises than a high schooler trying to find themselves at an open mic poetry night.

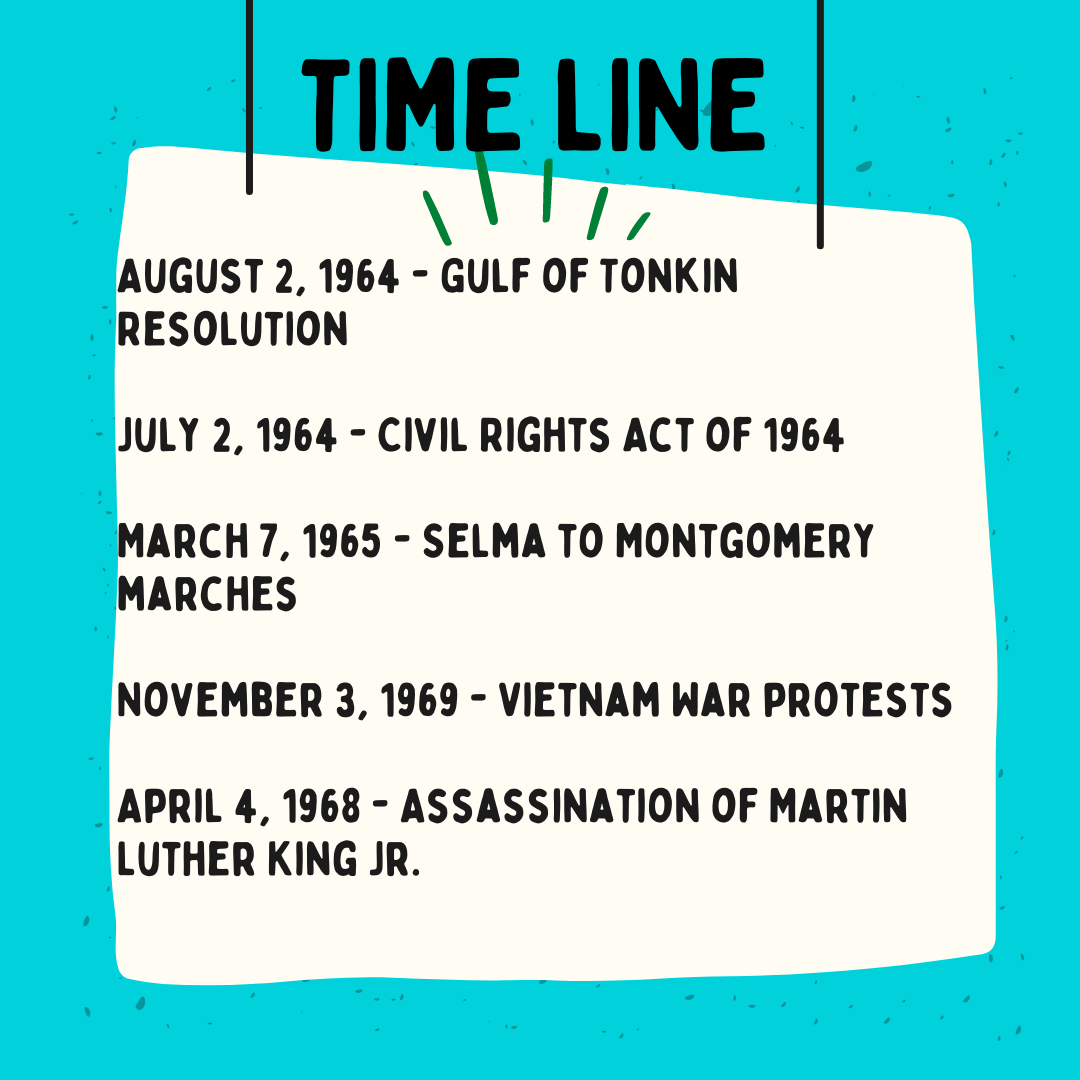

Let's start with the Civil Rights Act of '64, the legislation that was supposed to be the knight in shining armor riding in to slay the dragons of discrimination. Outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin—it was like saying, "Hey, let's try being decent human beings for a change." But oh boy, if only it were that simple. It tthat You can't just toss a law on the table and expect everyone to break out into a chorus of "Kumbaya suddenly." It was like trying to put out a wildfire with a squirt gun; you might make a little dent, but you'll still get singed.

Then, there was LBJ's War on Poverty, a noble effort to tackle economic inequality head-on. Medicare, Medicaid, and Head Start sound like a smorgasbord of social programs, right? Well, it was more like slapping Band-Aids on a sinking ship. Sure, it helped a bunch of folks, but poverty wasn't precisely packing its bags and waving goodbye. It was more like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic and crossing your fingers.

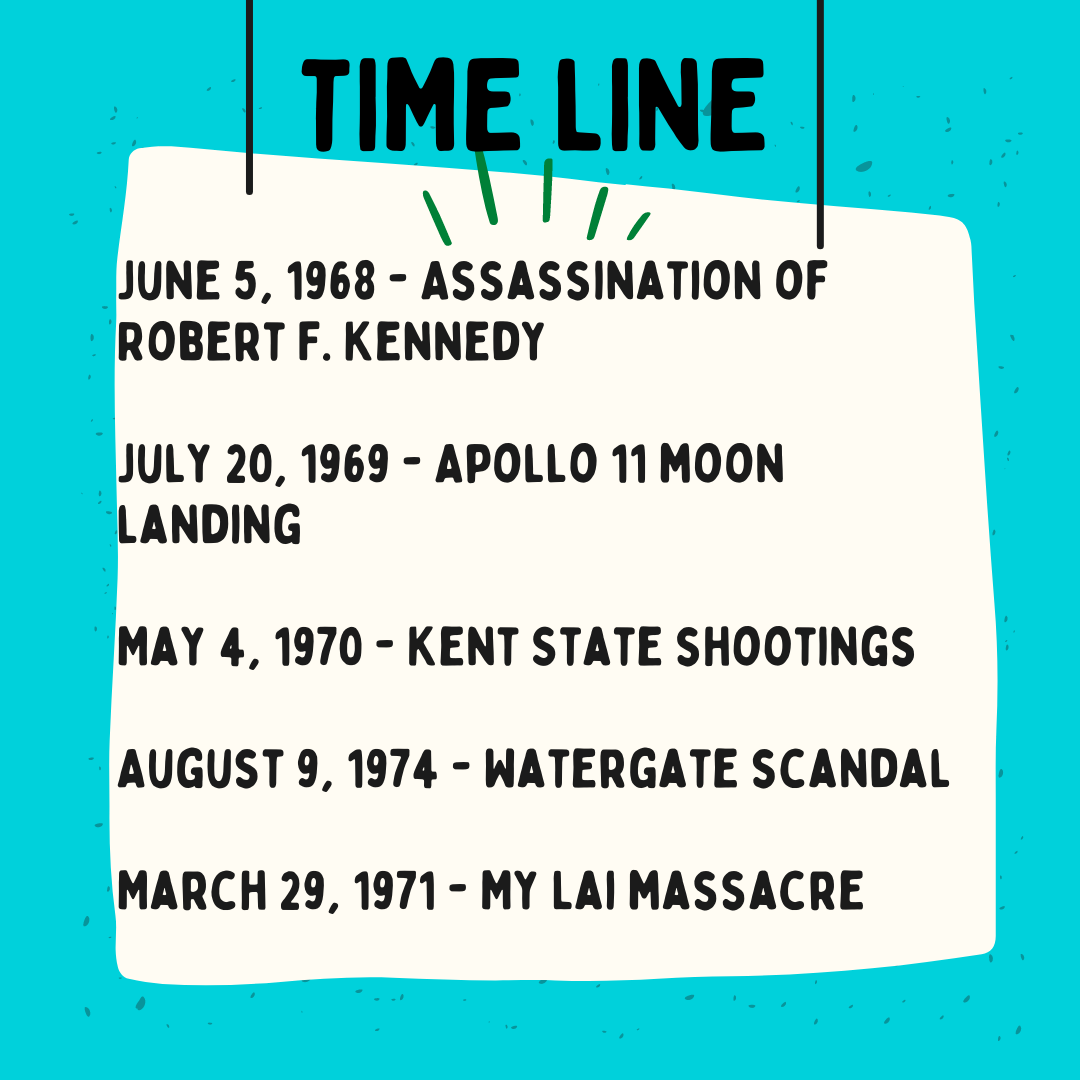

Now, we can talk about Vietnam. Ah yes, the war that felt like it dragged on longer than a "Brady Bunch" marathon. It was a quagmire of epic proportions, sucking in lives and resources faster than a black hole at a buffet. And the Tet Offensive of '68? That was like the universe giving America a cosmic wake-up call, a reminder that sticking your nose where it doesn't belong isn't the brightest idea.

And who could forget Watergate? The scandal made every other political scandal look like amateur hour at the local theater. Nixon and his crew pulled off stunts that would make Machiavelli blush. The break-in, the cover-up, the resignation was like watching a soap opera where the villains get away with it, at least for a little while.

It wasn't all doom and gloom. The '60s and '70s also gave us some genuine pearls of wisdom. The Civil Rights Movement showed us the power of standing up for what's right, even when the odds are stacked against you. The anti-war protests taught us that sometimes the loudest voice in the room is the one saying, "Hell no, we won't go!" And Watergate? Well, it showed us that even the big shots aren't immune to the long arm of the law, no matter how hard they try to wriggle out of it.

So, as we leaf through the dusty pages of history, let's not just dwell on the highs and lows but glean some lessons from them. Remember that change isn't always a walk in the park, but it's worth rolling up your sleeves for. And who knows, maybe we'll look back on these chaotic times and say, "Hey, we survived that. And we're all the wiser for it." Or maybe we'll pour ourselves another drink and raise a toast to the absurdity of it all.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The swinging sixties and the groovy seventies were a time when America was like a mixed bag of social chaos, political pandemonium, and enough cultural upheaval to make your head spin faster than a DJ scratching a record. It was a period when the nation went through more identity crises than a high schooler trying to find themselves at an open mic poetry night.

Let's start with the Civil Rights Act of '64, the legislation that was supposed to be the knight in shining armor riding in to slay the dragons of discrimination. Outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin—it was like saying, "Hey, let's try being decent human beings for a change." But oh boy, if only it were that simple. It tthat You can't just toss a law on the table and expect everyone to break out into a chorus of "Kumbaya suddenly." It was like trying to put out a wildfire with a squirt gun; you might make a little dent, but you'll still get singed.

Then, there was LBJ's War on Poverty, a noble effort to tackle economic inequality head-on. Medicare, Medicaid, and Head Start sound like a smorgasbord of social programs, right? Well, it was more like slapping Band-Aids on a sinking ship. Sure, it helped a bunch of folks, but poverty wasn't precisely packing its bags and waving goodbye. It was more like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic and crossing your fingers.

Now, we can talk about Vietnam. Ah yes, the war that felt like it dragged on longer than a "Brady Bunch" marathon. It was a quagmire of epic proportions, sucking in lives and resources faster than a black hole at a buffet. And the Tet Offensive of '68? That was like the universe giving America a cosmic wake-up call, a reminder that sticking your nose where it doesn't belong isn't the brightest idea.

And who could forget Watergate? The scandal made every other political scandal look like amateur hour at the local theater. Nixon and his crew pulled off stunts that would make Machiavelli blush. The break-in, the cover-up, the resignation was like watching a soap opera where the villains get away with it, at least for a little while.

It wasn't all doom and gloom. The '60s and '70s also gave us some genuine pearls of wisdom. The Civil Rights Movement showed us the power of standing up for what's right, even when the odds are stacked against you. The anti-war protests taught us that sometimes the loudest voice in the room is the one saying, "Hell no, we won't go!" And Watergate? Well, it showed us that even the big shots aren't immune to the long arm of the law, no matter how hard they try to wriggle out of it.

So, as we leaf through the dusty pages of history, let's not just dwell on the highs and lows but glean some lessons from them. Remember that change isn't always a walk in the park, but it's worth rolling up your sleeves for. And who knows, maybe we'll look back on these chaotic times and say, "Hey, we survived that. And we're all the wiser for it." Or maybe we'll pour ourselves another drink and raise a toast to the absurdity of it all.

THE RUNDOWN

- The years between 1964 and 1971 were marked by significant events that shaped America's political, social, and economic landscape, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which aimed to end discrimination based on race, religion, sex, and national origin, paving the way for equality in employment and education.

- President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty introduced programs like Medicare and Medicaid, providing healthcare and education opportunities to millions of Americans, illustrating positive efforts to combat poverty.

- However, the Vietnam War, which lasted from 1964 to 1975, divided the nation and resulted in the loss of over 58,000 American lives, demonstrating the devastating impact of war on society.

- The Watergate scandal in the early 1970s, involving a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters and subsequent cover-up by President Richard Nixon's administration, highlighted the dangers of unchecked government power and eroded public trust in the government.

- Despite the challenges and controversies of this era, studying it remains crucial today as it offers lessons on the importance of accountability, transparency, and the pursuit of justice in a democracy.

- By understanding the complexities of this period, we can work towards creating a more just and equitable future, drawing from both the successes, such as advancements in civil rights and poverty alleviation, and the failures, like the Vietnam War and Watergate scandal, as historical examples to guide us forward.

QUESTIONS

- What were some of the programs introduced during President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty? How did these programs aim to address poverty in America?

- Why was the Vietnam War so divisive among Americans? How did it affect the country socially and politically?

- What was the Watergate scandal, and why was it significant in American history? How did it affect people's trust in the government?

#10 Remove the Term Un-American from Your Vocabulary

In the vast saga of American history, few threads are as tangled and unraveled as the notion of being "Un-American." It's akin to receiving that infamous ugly sweater from Aunt Edna—scratchy, awkwardly sized, and definitely not something you'd want to flaunt in public. But alas, here we are, grappling with the knotty conundrum of what it truly means to be labeled as "un-American." It's the 1950s, and McCarthyism is running amok. Senator Joseph McCarthy is charging about like a bull in a china shop, brandishing his "Un-American" stamp as if it were a mark of distinction. Sneeze the wrong way, and you'd find yourself adorned with that scarlet letter quicker than you could say "democracy." Lives were upended, and careers torpedoed, all in the pursuit of sniffing out supposed commies as if they were hiding in every mom-and-pop store.

But let's rewind to the early 1900s and spare a thought for our immigrant pals from southern and eastern Europe. They were greeted with all the warmth of a skunk crashing a garden party, their customs and tongues deemed too exotic for the American taste buds. Suddenly, being "Un-American" meant having a surname with too many syllables or speaking a language that wasn't butchered English. Now, let's not overlook the silver lining amid this cloud of "Un-American" madness. Consider the civil rights movement – a bunch of folks boldly declaring, "Maybe segregating based on skin color isn't quite the American dream." Leaders like MLK Jr. were stirring the pot, challenging the norm like a rusty vending machine refusing to cough up change.

But here's the twist: we're still dancing to the same old tune in the 21st century. Just ask the LGBTQ community about being branded as "Un-American." It's like déjà vu but with a better fashion sense and a killer playlist. They're out there, fighting tooth and nail for the fundamental right to exist without being slapped with some outdated, discriminatory tag. So, what's the moral of this topsy-turvy tale? Well, it's time we stopped playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey with labels. Instead of fixating on our differences, it's time to celebrate the messy, glorious diversity that makes America a melting pot worth savoring. After all, nobody enjoys a burnt bottom, especially not in this grand tapestry we call home.

RUNDOWN

In the vast saga of American history, few threads are as tangled and unraveled as the notion of being "Un-American." It's akin to receiving that infamous ugly sweater from Aunt Edna—scratchy, awkwardly sized, and definitely not something you'd want to flaunt in public. But alas, here we are, grappling with the knotty conundrum of what it truly means to be labeled as "un-American." It's the 1950s, and McCarthyism is running amok. Senator Joseph McCarthy is charging about like a bull in a china shop, brandishing his "Un-American" stamp as if it were a mark of distinction. Sneeze the wrong way, and you'd find yourself adorned with that scarlet letter quicker than you could say "democracy." Lives were upended, and careers torpedoed, all in the pursuit of sniffing out supposed commies as if they were hiding in every mom-and-pop store.

But let's rewind to the early 1900s and spare a thought for our immigrant pals from southern and eastern Europe. They were greeted with all the warmth of a skunk crashing a garden party, their customs and tongues deemed too exotic for the American taste buds. Suddenly, being "Un-American" meant having a surname with too many syllables or speaking a language that wasn't butchered English. Now, let's not overlook the silver lining amid this cloud of "Un-American" madness. Consider the civil rights movement – a bunch of folks boldly declaring, "Maybe segregating based on skin color isn't quite the American dream." Leaders like MLK Jr. were stirring the pot, challenging the norm like a rusty vending machine refusing to cough up change.

But here's the twist: we're still dancing to the same old tune in the 21st century. Just ask the LGBTQ community about being branded as "Un-American." It's like déjà vu but with a better fashion sense and a killer playlist. They're out there, fighting tooth and nail for the fundamental right to exist without being slapped with some outdated, discriminatory tag. So, what's the moral of this topsy-turvy tale? Well, it's time we stopped playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey with labels. Instead of fixating on our differences, it's time to celebrate the messy, glorious diversity that makes America a melting pot worth savoring. After all, nobody enjoys a burnt bottom, especially not in this grand tapestry we call home.

RUNDOWN

- The historical concept of being "Un-American" is akin to an unsightly, ill-fitting garment, fraught with discomfort and social stigma.

- Throughout history, individuals and communities have been unfairly labeled as "Un-American," often leading to profound consequences such as ruined lives and shattered careers.

- Examples from McCarthyism in the 1950s to the discrimination faced by immigrants in the early 1900s highlight the pervasive nature of this label across different eras.

- However, movements like the civil rights struggle and advocacy for LGBTQ rights demonstrate resilience against such discriminatory categorizations.

- Despite progress, the 21st century still witnesses instances where individuals, particularly from marginalized groups, are unfairly branded as "Un-American."

- Embracing diversity and challenging the imposition of divisive labels can foster a more inclusive and equitable society.

STATE OF THE UNION

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- COMING SOON

READING

Carnes, Chapter 28: Collision Course, Abroad and at Home: 1946-1960

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

Carnes, Chapter 28: Collision Course, Abroad and at Home: 1946-1960

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... Before 1970, about a million abortions were done every year, of which only about ten thousand were legal. Perhaps a third of the women having illegal abortions- mostly poor people-had to be hospitalized for complications. How many thousands died as a result of these illegal abortions no one really knows. But the illegalization of abortion clearly worked against the poor, for the rich could manage either to have their baby or to have their abortion under safe conditions.

Court actions to do away with the laws against abortions were begun in over twenty states between 1968 and 1970, and public opinion grew stronger for the right of women to decide for themselves without government interference. In the book Sisterhood Is Powerful, an important collection of women's writing around 1970, an article by Lucinda Cisler, 'Unfinished Business: Birth Control,' said that 'abortion is a woman's right ... no one can veto her decision and compel her to bear a child against her will... .' In the spring of 1969 poll showed that 64 percent of those polled thought the decision on abortion was a private matter.

Finally, in early 1973, the Supreme Court decided (Roe v. Wade, Doe v. Eolton) that the state could prohibit abortions only in the last three months of pregnancy, that it could regulate abortion for health purposes during the second three months of pregnancy, and during the first three months, a woman and her doctor had the right to decide.

There was a push for child care centers, and although women did not succeed in getting much help from government, thousands of cooperative child care centers were set up..."

"... Before 1970, about a million abortions were done every year, of which only about ten thousand were legal. Perhaps a third of the women having illegal abortions- mostly poor people-had to be hospitalized for complications. How many thousands died as a result of these illegal abortions no one really knows. But the illegalization of abortion clearly worked against the poor, for the rich could manage either to have their baby or to have their abortion under safe conditions.

Court actions to do away with the laws against abortions were begun in over twenty states between 1968 and 1970, and public opinion grew stronger for the right of women to decide for themselves without government interference. In the book Sisterhood Is Powerful, an important collection of women's writing around 1970, an article by Lucinda Cisler, 'Unfinished Business: Birth Control,' said that 'abortion is a woman's right ... no one can veto her decision and compel her to bear a child against her will... .' In the spring of 1969 poll showed that 64 percent of those polled thought the decision on abortion was a private matter.

Finally, in early 1973, the Supreme Court decided (Roe v. Wade, Doe v. Eolton) that the state could prohibit abortions only in the last three months of pregnancy, that it could regulate abortion for health purposes during the second three months of pregnancy, and during the first three months, a woman and her doctor had the right to decide.

There was a push for child care centers, and although women did not succeed in getting much help from government, thousands of cooperative child care centers were set up..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court, hearing a pair of cases (generally referred to by the first case’s name, Roe v. Wade), concluded that Texas antiabortion laws violated a constitutional 'right to privacy.' Of course, no such phrase can be found in the Constitution. That, however, did not stop the Court from establishing—with no law’s ever being passed and no constitutional amendment’s ever being ratified—the premise that a woman had a constitutional right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. Later, sympathetic doctors would expand the context of health risk to the mother so broadly as to permit abortions almost on demand. Instantly the feminist movement leaped into action, portraying unborn babies as first, fetuses, then as 'blobs of tissue.' A battle with prolife forces led to an odd media acceptance of each side’s own terminology of itself: the labels that the media used were 'prochoice' (not 'proabortion') and 'prolife' not 'antichoice.' What was not so odd was the stunning explosion of abortions in the United States, which totaled at least 35

million over the first twenty-five years after Roe. Claims that without safe and legal abortions, women would die in abortion mills seemed to pale beside the stack of fetal bodies that resulted from the change in abortion laws.

For those who had championed the Pill as liberating women from the natural results of sex—babies—this proved nettlesome. More than 82 percent of the women who chose abortion in 1990 were unmarried. Had not the Pill protected them? Had it not liberated them to have sex without consequences? The bitter fact was that with the restraints of the church removed, the Pill and feminism had only exposed women to higher risks of pregnancy and, thus, 'eligibility' for an

abortion. It also exempted men almost totally from their role as fathers, leaving them the easy escape of pointing out to the female that abortion was an alternative to having an illegitimate child.

Fatherhood, and the role of men, was already under assault by feminist groups. By the 1970s, fathers had become a central target for the media, especially entertainment. Fathers were increasingly portrayed as buffoons, even as evil, on prime-time television. Comedies, according to one study of thirty years of network television, presented blue-collar or middle-class fathers as foolish, although less so than the portrayals of upper-class fathers..."

"... In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court, hearing a pair of cases (generally referred to by the first case’s name, Roe v. Wade), concluded that Texas antiabortion laws violated a constitutional 'right to privacy.' Of course, no such phrase can be found in the Constitution. That, however, did not stop the Court from establishing—with no law’s ever being passed and no constitutional amendment’s ever being ratified—the premise that a woman had a constitutional right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. Later, sympathetic doctors would expand the context of health risk to the mother so broadly as to permit abortions almost on demand. Instantly the feminist movement leaped into action, portraying unborn babies as first, fetuses, then as 'blobs of tissue.' A battle with prolife forces led to an odd media acceptance of each side’s own terminology of itself: the labels that the media used were 'prochoice' (not 'proabortion') and 'prolife' not 'antichoice.' What was not so odd was the stunning explosion of abortions in the United States, which totaled at least 35

million over the first twenty-five years after Roe. Claims that without safe and legal abortions, women would die in abortion mills seemed to pale beside the stack of fetal bodies that resulted from the change in abortion laws.

For those who had championed the Pill as liberating women from the natural results of sex—babies—this proved nettlesome. More than 82 percent of the women who chose abortion in 1990 were unmarried. Had not the Pill protected them? Had it not liberated them to have sex without consequences? The bitter fact was that with the restraints of the church removed, the Pill and feminism had only exposed women to higher risks of pregnancy and, thus, 'eligibility' for an

abortion. It also exempted men almost totally from their role as fathers, leaving them the easy escape of pointing out to the female that abortion was an alternative to having an illegitimate child.

Fatherhood, and the role of men, was already under assault by feminist groups. By the 1970s, fathers had become a central target for the media, especially entertainment. Fathers were increasingly portrayed as buffoons, even as evil, on prime-time television. Comedies, according to one study of thirty years of network television, presented blue-collar or middle-class fathers as foolish, although less so than the portrayals of upper-class fathers..."

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"... Prostitutes undermined virtually every sexual taboo that limited the freedom of women. The birth control devices that had circulated among the rabble of early American cities came under attack by the middle of the nineteenth century, when contraceptives were used widely and shamelessly. A visitor to Boston noted in 1872 that there was “hardly a newspaper that does not contain their open and printed advertisements, or a drug store whose shelves are not crowded with nostrums publicly and unblushingly displayed.” The production and distribution of devices that made sex purely recreational was, according to the historian Andrea Tone, 'a robust and increasingly visible commerce in illicit products and pleasures that seemed to encourage sexual license by freeing sex from marriage and childbearing.' The growing numbers of prostitutes in the mid-nineteenth century greatly supported this market, then kept it alive when moral reformers threatened to kill it. In the 1860s and 1870s, several books with titles such as Serpents in the Doves’ Nest and Satan in Society condemned birth control as a violation of 'the laws of heaven,' 'the invention of hell,' and a 'hydra-headed monster' bent on killing the American family. These complaints became law in 1873 with the passage by the U.S. Congress of an Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use, commonly called the Comstock Law. The law, named after the anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock, made it illegal to distribute through the U.S. Postal Service any 'obscene, lewd, or lascivious' materials 'or any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or producing of abortion...'"

"... Prostitutes undermined virtually every sexual taboo that limited the freedom of women. The birth control devices that had circulated among the rabble of early American cities came under attack by the middle of the nineteenth century, when contraceptives were used widely and shamelessly. A visitor to Boston noted in 1872 that there was “hardly a newspaper that does not contain their open and printed advertisements, or a drug store whose shelves are not crowded with nostrums publicly and unblushingly displayed.” The production and distribution of devices that made sex purely recreational was, according to the historian Andrea Tone, 'a robust and increasingly visible commerce in illicit products and pleasures that seemed to encourage sexual license by freeing sex from marriage and childbearing.' The growing numbers of prostitutes in the mid-nineteenth century greatly supported this market, then kept it alive when moral reformers threatened to kill it. In the 1860s and 1870s, several books with titles such as Serpents in the Doves’ Nest and Satan in Society condemned birth control as a violation of 'the laws of heaven,' 'the invention of hell,' and a 'hydra-headed monster' bent on killing the American family. These complaints became law in 1873 with the passage by the U.S. Congress of an Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use, commonly called the Comstock Law. The law, named after the anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock, made it illegal to distribute through the U.S. Postal Service any 'obscene, lewd, or lascivious' materials 'or any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or producing of abortion...'"

What Does Professor Lancaster Think?

Back in the 1800s, when corsets were cinched tighter than a miser's purse strings and societal rules were stricter than a Victorian governess, women were like, "Uh, no thanks!" Fed up with being treated like walking baby factories, they decided to shake things up. Cue the suffragettes, the OG squad of feminists, ready to kick patriarchy where it hurts most—right in the voting booth.

Imagine Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the Thelma and Louise of women's rights, causing a ruckus in their hoop skirts like two rebels with a cause. They weren't just demanding the vote; they were demanding control over their bodies. For them, birth control wasn't just about dodging pregnancies; it was about saying, "Sorry, not tonight, I have a headache... for the next 18 years." Condoms and pills weren't just tools; they were the golden tickets to sexual liberation.

But then along came the Comstock Law, raining on everyone's parade like a real Debbie Downer. Named after the ultimate party pooper, Anthony Comstock, this law didn't just ruin your Saturday night; it criminalized everything from rubbers to pamphlets about abortion. Because who needs women making decisions when you can legislate them into submission, right? And let's not forget the resistance to change. Men clinging to their patriarchal privileges like they were going out of style (spoiler alert: they were). Media pushing stereotypes of clueless dads and helpless homemakers, as if changing diapers required a Ph.D. in rocket science.

But amid that repression, badass feminists emerged, ready to shake things up. The Seneca Falls Convention wasn't just a meeting; it was Woodstock for feminists, minus the drugs and Jimi Hendrix. And then there's Margaret Sanger, the rebel with a cause, sticking it to the man by opening the first birth control clinic in the US. Legal threats? Bring them on. Conservative backlash? She laughed in its face. Sanger wasn't just fighting for reproductive rights; she was fighting for the right to live life on her terms.

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and we're still fighting for equality and reproductive freedom. The battles of our foremothers weren't just stories; they were calls to arms for a future where everyone controls their bodies. And if that's not worth raising a glass—or a middle finger—to, then I don't know what is.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

Back in the 1800s, when corsets were cinched tighter than a miser's purse strings and societal rules were stricter than a Victorian governess, women were like, "Uh, no thanks!" Fed up with being treated like walking baby factories, they decided to shake things up. Cue the suffragettes, the OG squad of feminists, ready to kick patriarchy where it hurts most—right in the voting booth.

Imagine Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the Thelma and Louise of women's rights, causing a ruckus in their hoop skirts like two rebels with a cause. They weren't just demanding the vote; they were demanding control over their bodies. For them, birth control wasn't just about dodging pregnancies; it was about saying, "Sorry, not tonight, I have a headache... for the next 18 years." Condoms and pills weren't just tools; they were the golden tickets to sexual liberation.

But then along came the Comstock Law, raining on everyone's parade like a real Debbie Downer. Named after the ultimate party pooper, Anthony Comstock, this law didn't just ruin your Saturday night; it criminalized everything from rubbers to pamphlets about abortion. Because who needs women making decisions when you can legislate them into submission, right? And let's not forget the resistance to change. Men clinging to their patriarchal privileges like they were going out of style (spoiler alert: they were). Media pushing stereotypes of clueless dads and helpless homemakers, as if changing diapers required a Ph.D. in rocket science.

But amid that repression, badass feminists emerged, ready to shake things up. The Seneca Falls Convention wasn't just a meeting; it was Woodstock for feminists, minus the drugs and Jimi Hendrix. And then there's Margaret Sanger, the rebel with a cause, sticking it to the man by opening the first birth control clinic in the US. Legal threats? Bring them on. Conservative backlash? She laughed in its face. Sanger wasn't just fighting for reproductive rights; she was fighting for the right to live life on her terms.

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and we're still fighting for equality and reproductive freedom. The battles of our foremothers weren't just stories; they were calls to arms for a future where everyone controls their bodies. And if that's not worth raising a glass—or a middle finger—to, then I don't know what is.

THE RUNDOWN

- In the 1800s, women in America wanted more control over their lives and bodies, but laws like the Comstock Law made it hard.

- The Comstock Law in 1873 stopped women from getting birth control, which made it difficult for them to plan families.

- Some people didn't like women challenging their traditional roles, and the media often showed fathers as better than mothers.

- Brave women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony fought for women's rights, including the right to vote.

- Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in 1916, even though it was against the law, to help women control their own bodies.

- Learning about these struggles helps us understand why fighting for gender equality and reproductive freedom is still important today.

QUESTIONS

- How did the passage of the Comstock Law in 1873 reflect broader societal attitudes towards women's autonomy and reproductive rights in 19th century America?

- In what ways did the dissemination of contraceptive devices challenge traditional gender roles and empower women to pursue sexual freedom and autonomy?

- What role did feminist activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony play in advocating for women's rights and challenging societal norms in the 1800s?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

In the shadows of history's forgotten corners, a rebellion brewed, not with guns and glory, but with lipstick and leather. The Stonewall uprising emerged from the depths of Greenwich Village, where the Stonewall Inn stood as a refuge for those who loved differently. Amidst the grime and chaos of New York City, within the walls of this rundown joint, society's castaways found sanctuary.Fueled by defiance and a desire for recognition, the patrons of Stonewall refused to be silenced any longer. With high heels and hair spray as their weapons, they took to the streets, declaring war on a world that denied their humanity. Despite facing tear gas and oppression, their persistence paid off, gradually garnering visibility and respect for the LGBTQ+ community.

In the shadows of history's forgotten corners, a rebellion brewed, not with guns and glory, but with lipstick and leather. The Stonewall uprising emerged from the depths of Greenwich Village, where the Stonewall Inn stood as a refuge for those who loved differently. Amidst the grime and chaos of New York City, within the walls of this rundown joint, society's castaways found sanctuary.Fueled by defiance and a desire for recognition, the patrons of Stonewall refused to be silenced any longer. With high heels and hair spray as their weapons, they took to the streets, declaring war on a world that denied their humanity. Despite facing tear gas and oppression, their persistence paid off, gradually garnering visibility and respect for the LGBTQ+ community.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- 1964 Civil Rights Act of 1964

- 1964 Ella Baker Makes a Plea for Black Lives

- 1964 Gulf of Tonkin

- 1964 'Mississippi Burning' Murders

- 1965 Malcolm X Shot to Death

- 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration and Nationality Act

- 1966 Cesar Chavez

- 1967 The Tierra Amarilla Courthouse Is Raided

- 1967 The Odyssey

- 1968 Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

- 1968 My Lai massacre

- 1968 Special Olympics

- 1969: Attacks on the Black Panther Party’s breakfast program

- 1969 Stonewall Inn

- 1969 The moon landing

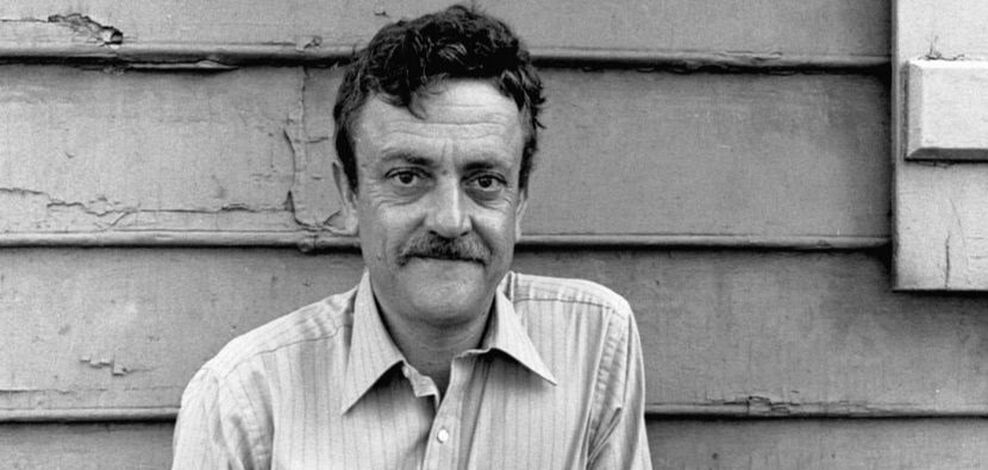

- 1969 Kurt Vonnegut

- 1969 Fred Hampton

- 1969 Jimi Hendrix Plays the Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock

- 1969 Johnny Cash Walk the Line

- 1970- Fashion

- 1970- Birth of Rap Music

- 1971 Hunter S. Thompson

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

ACTIVITY: "Mapping Activity: US History (1964 CE - 1971 CE)"

Objective: Your task is to create a visual representation of the important events, people, and themes in US history from 1964 to 1971.

Materials Needed:

ACTIVITY: Role Reversal Activity: "Voices of the 1960s"

Objective:

Note: Approach your role with sensitivity and empathy, recognizing the complexities of individuals' experiences during this period. Respectfully engage with your classmates and explore differing viewpoints to deepen your understanding of the era.

Role Examples:

ACTIVITY: "Mapping Activity: US History (1964 CE - 1971 CE)"

Objective: Your task is to create a visual representation of the important events, people, and themes in US history from 1964 to 1971.

Materials Needed:

- Large whiteboard or poster paper

- Markers or colored pens

- Sticky notes or index cards (optional)

- Introduction to the Time Period: Start by understanding the historical context of the years 1964 to 1971. Learn about major events like the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the counterculture.

- Think about and write down important events, individuals, and themes from this period. Use sticky notes or index cards for each item.

- For example, consider events like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, protests against the Vietnam War, cultural movements like Woodstock, and significant achievements like the Apollo 11 moon landing.

- Place a central concept, "US History (1964-1971)," in the middle of your whiteboard or poster.

- Organize your sticky notes or index cards around this central concept, grouping related events and themes together.

- Use markers or colored pens to draw lines or arrows connecting related concepts. Show how events are linked in terms of cause and effect, chronology, or themes.

- Write brief descriptions or explanations for each concept on your concept map to provide context and clarity.

- Step back and review your concept map. Make sure it accurately reflects the important events and themes of the period.

- Look for any missing connections or events that should be included. Make adjustments as needed.

- Take a moment to think about the significance of the events and themes you've depicted. Consider how they continue to impact society and politics today.

ACTIVITY: Role Reversal Activity: "Voices of the 1960s"

Objective:

- Gain insight into the diverse perspectives, motivations, and experiences of individuals during the turbulent period of US history from 1964 to 1971.

- Prepare:You will be assigned a specific role to research and embody during the activity. Your role could represent various perspectives such as activists, politicians, soldiers, protesters, or civilians.

- Use provided resources to research your assigned role thoroughly. Consider the individual's background, beliefs, and actions during the 1960s.

- Take time to gather information about your assigned role. Look into their historical context, beliefs, and experiences during the 1960s.

- Come to class prepared to embody your assigned role.

- Engage in a structured discussion or debate with your classmates, staying in character. Express your viewpoints, motivations, and experiences from the perspective of your assigned role.

- Ask questions and respond authentically based on your research.

- After the activity, reflect on your experience portraying your assigned role.

- Consider how your understanding of the historical period and the perspectives of various individuals may have changed through the activity.

Note: Approach your role with sensitivity and empathy, recognizing the complexities of individuals' experiences during this period. Respectfully engage with your classmates and explore differing viewpoints to deepen your understanding of the era.

Role Examples:

- Civil Rights Activist (e.g., Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X)

- Anti-War Protester

- Vietnam War Veteran

- Civilian Observer

- Government Official (e.g., President Lyndon B. Johnson, President Richard Nixon)

- Feminist Activist

- Conservative Political Figure

- Student Activist (e.g., member of Students for a Democratic Society)

- Journalist or Reporter

- Average Citizen with varying political beliefs

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

The swinging sixties and the groovy seventies, when America mixed progress, chaos, and corruption like a tipsy bartender. Bell bottoms, flower power, and presidents with names straight out of a sitcom navigating a landscape as shaky as a margarita on a wobbly table.

Take a stroll down memory lane with me, starting with the Civil Rights Act of '64, when Uncle Sam decided discrimination wasn't his cup of tea. Lyndon B. Johnson, with a drawl thicker than molasses, signed that baby into law, aiming to give bigotry a swift kick where it hurts—the legislation. No more whites-only water fountains or "Sorry, we don't serve your kind here" nonsense. It was like America finally found the rhythm to its dance, albeit with a few folks still tripping over their feet.

But buckle up because while LBJ was playing the hero, he was also gearing up for a different kind of drama: Vietnam. The war that devoured lives like Pac-Man on a power trip. It started innocently enough with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a presidential permission slip for mischief signed in '64. Fast forward a bit, and suddenly, America found itself knee-deep in the rice paddies of Southeast Asia, scratching its head, wondering how it got there. Protesters hit the streets with signs screaming, "Make love, not napalm," and "Hell no, we won't go!" Vietnam crashed America's party like an unwanted guest, turning flower children into draft dodgers faster than you could say, "Give peace a chance."

Meanwhile, Nixon was busy playing political poker, and boy, he had a few tricks up his sleeve. Watergate, the scandal to end all scandals, left the nation feeling like the universe had punked it. It started with a break-in, a handful of sneaky burglars trying to score some campaign dirt. But like any good crime flick, things escalated faster than you could say, "I am not a crook." Suddenly, tapes went missing, fingers were pointed, and the White House was sweating bullets. Nixon tried to dodge and weave his way out of trouble, but in the end, truth crashed down like a chandelier in a bar brawl. Adios, Tricky Dick, and hello to a nation wondering if anyone in D.C. could be trusted.

And let's not forget the War on Poverty, a noble endeavor that was about as effective as using a band-aid on a gunshot wound. Medicare and Medicaid were supposed to swoop in and save the day for America's downtrodden, but bureaucracy had other plans. Sure, there were a few success stories, but for every family lifted out of poverty, there were a dozen more stuck in the same old rut. It was like trying to bail out the Titanic with a teacup—a valiant effort but ultimately destined to sink.

So, what's the takeaway from this topsy-turvy tale? Perhaps it's that history has a knack for slapstick comedy, or maybe it's a cautionary tale about power and its ability to turn you into a national punchline. Either way, the '60s and '70s were a rollercoaster ride through the soul of America, a time when the nation was trying to find itself amid the madness. And hey, if nothing else, it gave us some killer tunes and unforgettable fashion statements.

Or, in other words:

The swinging sixties and the groovy seventies, when America mixed progress, chaos, and corruption like a tipsy bartender. Bell bottoms, flower power, and presidents with names straight out of a sitcom navigating a landscape as shaky as a margarita on a wobbly table.

Take a stroll down memory lane with me, starting with the Civil Rights Act of '64, when Uncle Sam decided discrimination wasn't his cup of tea. Lyndon B. Johnson, with a drawl thicker than molasses, signed that baby into law, aiming to give bigotry a swift kick where it hurts—the legislation. No more whites-only water fountains or "Sorry, we don't serve your kind here" nonsense. It was like America finally found the rhythm to its dance, albeit with a few folks still tripping over their feet.

But buckle up because while LBJ was playing the hero, he was also gearing up for a different kind of drama: Vietnam. The war that devoured lives like Pac-Man on a power trip. It started innocently enough with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a presidential permission slip for mischief signed in '64. Fast forward a bit, and suddenly, America found itself knee-deep in the rice paddies of Southeast Asia, scratching its head, wondering how it got there. Protesters hit the streets with signs screaming, "Make love, not napalm," and "Hell no, we won't go!" Vietnam crashed America's party like an unwanted guest, turning flower children into draft dodgers faster than you could say, "Give peace a chance."

Meanwhile, Nixon was busy playing political poker, and boy, he had a few tricks up his sleeve. Watergate, the scandal to end all scandals, left the nation feeling like the universe had punked it. It started with a break-in, a handful of sneaky burglars trying to score some campaign dirt. But like any good crime flick, things escalated faster than you could say, "I am not a crook." Suddenly, tapes went missing, fingers were pointed, and the White House was sweating bullets. Nixon tried to dodge and weave his way out of trouble, but in the end, truth crashed down like a chandelier in a bar brawl. Adios, Tricky Dick, and hello to a nation wondering if anyone in D.C. could be trusted.

And let's not forget the War on Poverty, a noble endeavor that was about as effective as using a band-aid on a gunshot wound. Medicare and Medicaid were supposed to swoop in and save the day for America's downtrodden, but bureaucracy had other plans. Sure, there were a few success stories, but for every family lifted out of poverty, there were a dozen more stuck in the same old rut. It was like trying to bail out the Titanic with a teacup—a valiant effort but ultimately destined to sink.

So, what's the takeaway from this topsy-turvy tale? Perhaps it's that history has a knack for slapstick comedy, or maybe it's a cautionary tale about power and its ability to turn you into a national punchline. Either way, the '60s and '70s were a rollercoaster ride through the soul of America, a time when the nation was trying to find itself amid the madness. And hey, if nothing else, it gave us some killer tunes and unforgettable fashion statements.

Or, in other words:

- 1964-1971: An era marked by profound shifts in American society!

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: A landmark legislation that banned discrimination based on race, religion, and other factors.

- President Johnson's War on Poverty: Implemented sweeping initiatives such as Medicare and Medicaid to provide assistance to the economically disadvantaged.

- Vietnam War: Provoked widespread dissent and anguish, claiming countless American lives and polarizing the nation.

- Watergate scandal: Uncovered corruption at the highest levels of government, leading to a crisis of confidence among the public.

- Studying this period underscores the imperative of holding leaders accountable and upholding principles of transparency and integrity in governance

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #11

Harrison Salisbury was a renowned American journalist who reported on major global events such as the Soviet Union, China, and the Vietnam War. He was known for his incisive reporting and ability to bring a human dimension to international conflicts. In his later years, he hosted a television interview series called "Behind the Lines," which featured discussions with notable journalists about their experiences covering war zones and other challenging assignments. The show was highly regarded for its in-depth and nuanced exploration of the ethical and practical considerations of reporting from dangerous locations. Watch this video interview and answer the following:

- Forum Discussion #11

Forum Discussion #11

Harrison Salisbury was a renowned American journalist who reported on major global events such as the Soviet Union, China, and the Vietnam War. He was known for his incisive reporting and ability to bring a human dimension to international conflicts. In his later years, he hosted a television interview series called "Behind the Lines," which featured discussions with notable journalists about their experiences covering war zones and other challenging assignments. The show was highly regarded for its in-depth and nuanced exploration of the ethical and practical considerations of reporting from dangerous locations. Watch this video interview and answer the following:

What is your opinion on the concept of gonzo journalism as described by Hunter S. Thompson? Do you think there is a place for this writing style in modern journalism, or do you believe it undermines the credibility of factual reporting? Additionally, should readers be responsible for discerning when a writer uses hyperbole or exaggeration for effect or is it the writer's responsibility to make it clear to their audience?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Hold onto your hats because we're plunging into the madcap world of literary legends with Hunter S. Thompson at the helm. Picture this: a man fueled by a cocktail of bourbon and righteous rage, careening through American culture with a typewriter in one hand and a mind buzzing with psychedelics in the other. That's our protagonist. Gonzo journalism isn't just reporting; it's a wild ride where truth, lies, and sheer lunacy collide. Thompson didn't just write stories; he orchestrated explosions of reality that left readers questioning everything. "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" wasn't merely a book; it was a psychedelic journey through the underbelly of the American Dream.

Thompson cut his teeth in the gritty world of journalism, prowling the streets like a whiskey-fueled detective in search of the next big scoop. He was a master of words, blending fact and fiction into intoxicating narratives. And while he occasionally veered into political cynicism, who could blame him in a world gone mad? Thompson's rebel spirit knew no bounds, even if it meant clashing with editorial constraints. Ultimately, whether hailed as a hero or dismissed as a madman, his legacy remains a testament to the unpredictable thrill of gonzo journalism.

What is your opinion on the concept of gonzo journalism as described by Hunter S. Thompson? Do you think there is a place for this writing style in modern journalism, or do you believe it undermines the credibility of factual reporting? Additionally, should readers be responsible for discerning when a writer uses hyperbole or exaggeration for effect or is it the writer's responsibility to make it clear to their audience?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Hold onto your hats because we're plunging into the madcap world of literary legends with Hunter S. Thompson at the helm. Picture this: a man fueled by a cocktail of bourbon and righteous rage, careening through American culture with a typewriter in one hand and a mind buzzing with psychedelics in the other. That's our protagonist. Gonzo journalism isn't just reporting; it's a wild ride where truth, lies, and sheer lunacy collide. Thompson didn't just write stories; he orchestrated explosions of reality that left readers questioning everything. "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" wasn't merely a book; it was a psychedelic journey through the underbelly of the American Dream.

Thompson cut his teeth in the gritty world of journalism, prowling the streets like a whiskey-fueled detective in search of the next big scoop. He was a master of words, blending fact and fiction into intoxicating narratives. And while he occasionally veered into political cynicism, who could blame him in a world gone mad? Thompson's rebel spirit knew no bounds, even if it meant clashing with editorial constraints. Ultimately, whether hailed as a hero or dismissed as a madman, his legacy remains a testament to the unpredictable thrill of gonzo journalism.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.