HST 202 Module #7

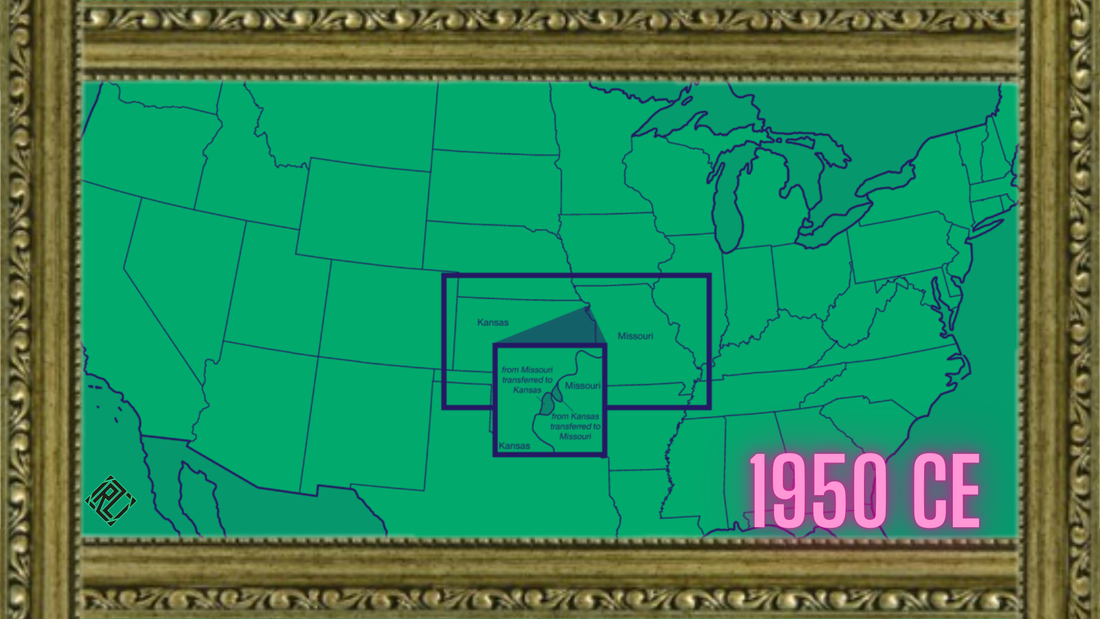

Week 7: Teenage Wasteland (1939 CE - 1950 CE)

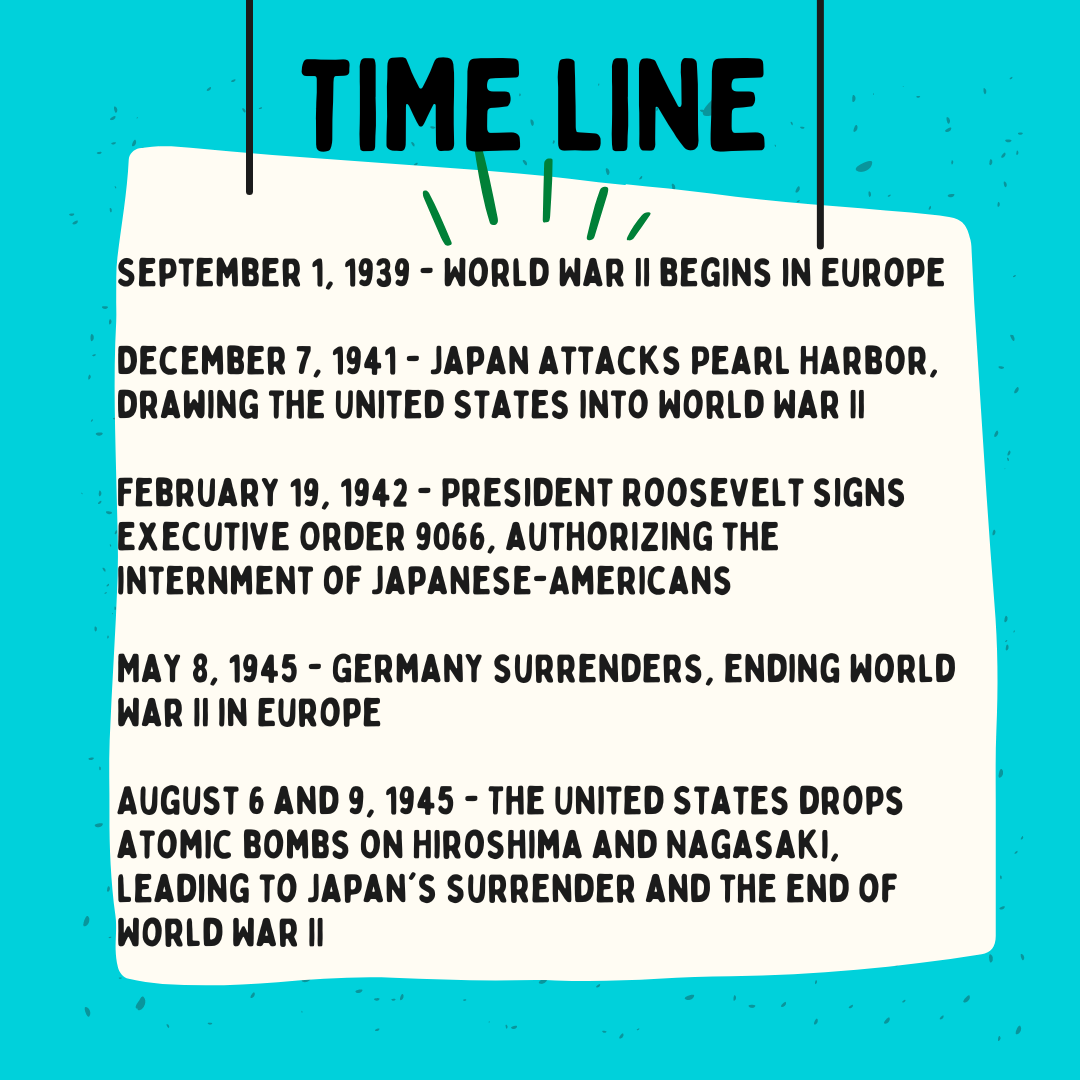

The tumultuous era from 1939 to 1950 in the United States was one where triumphs mingled with tragedies akin to old acquaintances at a reunion. It's a narrative woven with the complexities of human endeavor and error, resembling a quilt stitched by a temperamental artisan with inclinations toward brilliance and disaster. Imagine this: Uncle Sam, the emblematic superhero draped in red, white, and blue, emerging to thwart the Axis powers during World War II. The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor catalyzes a nationwide mobilization, with Rosie the Riveter churning out warplanes with the efficiency of a modern coffee chain's pumpkin spice latte production.

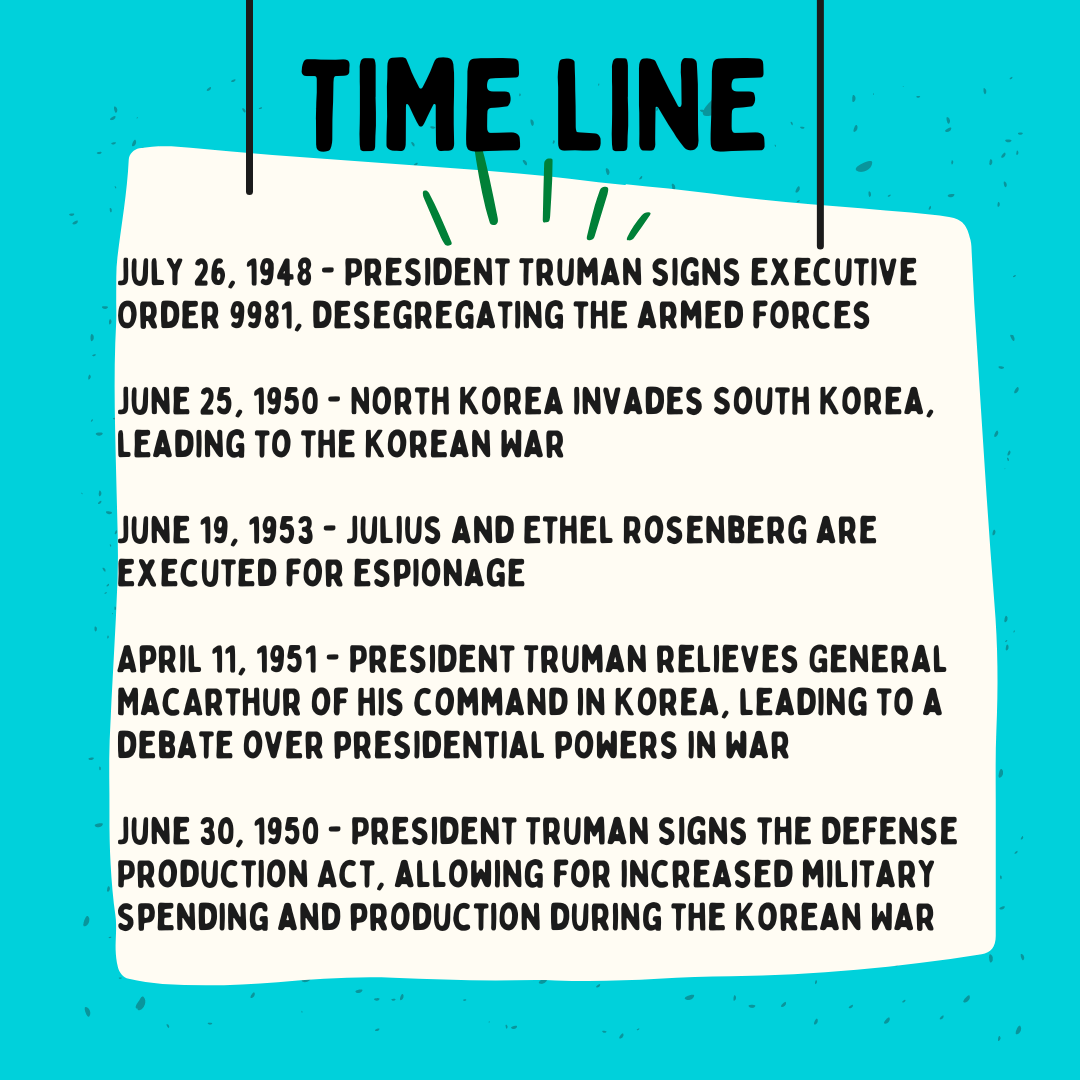

Simultaneously, Truman, unexpectedly thrust into the presidency following FDR's passing, initiated efforts to desegregate the military. It's as though the nation is awakening to the realization that segregation is as antiquated as a polio outbreak in a swimming pool. But hold your breath, for not all moments are marked by victory parades and celebrations. We confront the dark chapters of Japanese-American internment camps, where individuals with even a trace of Japanese heritage were confined behind barbed wire fences, challenging the notion of America as the land of freedom.

Then comes the Red Scare, led by McCarthy and his cohorts, reminiscent of a witch hunt eclipsing even Salem's infamy. Suspicions of communist sympathies run rampant, leading to blocklisting at the mere hint of leftist leanings. Yet amidst these shadows, the United Nations emerges as a beacon of international cooperation, akin to diplomatic Avengers, fostering collaboration in the intricate realm of global politics.

Fast forward to the present, and echoes of the past reverberate. We grapple with persistent specters of racism, inequality, and political apprehension, akin to an outspoken relative at a holiday feast fixated on a contentious family recipe. So, what lessons emerge from this whirlwind journey through history? Perhaps it's the recognition of our nation's paradoxes, stumbling forward with uncertainties yet united in our collective journey. Through humor and reflection on our missteps, there's hope that we may stumble towards a brighter tomorrow, or at least one less obscured by shadows.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The tumultuous era from 1939 to 1950 in the United States was one where triumphs mingled with tragedies akin to old acquaintances at a reunion. It's a narrative woven with the complexities of human endeavor and error, resembling a quilt stitched by a temperamental artisan with inclinations toward brilliance and disaster. Imagine this: Uncle Sam, the emblematic superhero draped in red, white, and blue, emerging to thwart the Axis powers during World War II. The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor catalyzes a nationwide mobilization, with Rosie the Riveter churning out warplanes with the efficiency of a modern coffee chain's pumpkin spice latte production.

Simultaneously, Truman, unexpectedly thrust into the presidency following FDR's passing, initiated efforts to desegregate the military. It's as though the nation is awakening to the realization that segregation is as antiquated as a polio outbreak in a swimming pool. But hold your breath, for not all moments are marked by victory parades and celebrations. We confront the dark chapters of Japanese-American internment camps, where individuals with even a trace of Japanese heritage were confined behind barbed wire fences, challenging the notion of America as the land of freedom.

Then comes the Red Scare, led by McCarthy and his cohorts, reminiscent of a witch hunt eclipsing even Salem's infamy. Suspicions of communist sympathies run rampant, leading to blocklisting at the mere hint of leftist leanings. Yet amidst these shadows, the United Nations emerges as a beacon of international cooperation, akin to diplomatic Avengers, fostering collaboration in the intricate realm of global politics.

Fast forward to the present, and echoes of the past reverberate. We grapple with persistent specters of racism, inequality, and political apprehension, akin to an outspoken relative at a holiday feast fixated on a contentious family recipe. So, what lessons emerge from this whirlwind journey through history? Perhaps it's the recognition of our nation's paradoxes, stumbling forward with uncertainties yet united in our collective journey. Through humor and reflection on our missteps, there's hope that we may stumble towards a brighter tomorrow, or at least one less obscured by shadows.

THE RUNDOWN

- Between 1939 and 1950, America faced both triumphs and tragedies, like a rollercoaster ride of ups and downs.

- Uncle Sam, like a superhero, stepped in during World War II, but there were also dark times, like Japanese-American internment camps.

- President Truman tried to end segregation in the military, showing progress, but there was also fear of communism during the Red Scare.

- Despite challenges, the United Nations brought countries together, acting like a team of superheroes for diplomacy.

- Today, America still deals with issues like racism and political tension, but there's hope for a better future if we learn from the past.

- So, while America has its flaws, by working together and learning from mistakes, we can make progress toward a brighter tomorrow.

QUESTIONS

- Consider the role of humor and reflection in navigating difficult moments in history. How can a balanced approach to acknowledging past missteps contribute to a more hopeful future?

- Reflect on the idea of a "brighter tomorrow" amidst uncertainties and shadows in today's world. What steps can individuals and communities take to move towards a more inclusive and equitable future?

- Explore the notion of collective responsibility in shaping the trajectory of history. How can understanding the interconnectedness of past, present, and future inform our actions in the present moment?

#7 Historiography is Important and is Never Stagnant.

In the intricate tapestry of human chronicles, historiography emerges as the voyeuristic aperture through which we peer into antiquity, albeit clouded by the biases and distortions inherent in subjective interpretation. It resembles deciphering hieroglyphs through the haze of intoxication; while the essence may be discerned, the finer details remain obscured.

Imagine this: Herodotus, the original chronicler, striding through ancient Greece with an air of ownership, weaving narratives of deities, monsters, and drama rivaling the climax of "Keeping Up with the Spartans." Skip ahead a few millennia, and Howard Zinn detonates truth bombs like confetti at a rebellion-themed soirée, unsettling historical narratives akin to a bartender vigorously shaking a cocktail.

Yet, let's delve into revisionism, shall we? It's akin to hitting the "undo" button on history's greatest hits compilation. Consider Native American history: once relegated to footnotes by those viewing Columbus as merely a geographically befuddled Italian, it now basks in the limelight. Thanks to movements like the American Indian Movement and voices like Vine Deloria Jr., a fresh perspective emerges that refuses to gloss over centuries of oppression akin to a poor Tinder profile.

Historiography is not merely about stirring the pot but infusing zest into an otherwise bland concoction. Think of it as a culinary experiment gone deliciously awry, with historians tossing in new ingredients akin to contestants on "Chopped: Ancient Civilizations Edition." Case in point: the Dead Sea Scrolls. Forget Indiana Jones; these artifacts are true treasures, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the lives of ancient Essenes and igniting debates fiercer than a chili-eating contest.

However, let's not deceive ourselves; historiography harbors biases like street vendors peddling counterfeit wares. Recall the Cold War-era scholars who perceived communists lurking behind every corner. It turns out that impartiality wasn't their forte. And the Nazi propaganda machine? It churned out historical narratives akin to Goebbels-approved bedtime tales.

In today's era of misinformation and alternative truths, historiography assumes unprecedented significance. It is the antidote to historical forgetfulness, the shield against cognitive lethargy. By acknowledging our biases and scrutinizing the narratives we ingest, we inch closer to an honest comprehension of the past—one that confronts human existence's messy, intricate reality. So here's to historiography, the unsung hero of the annals. Without it, we'd flounder in a sea of half-truths and falsehoods, destined to replay the errors of yesteryears like a broken record. Here's to reshaping history, one revision at a time.

THE RUNDOWN

In the intricate tapestry of human chronicles, historiography emerges as the voyeuristic aperture through which we peer into antiquity, albeit clouded by the biases and distortions inherent in subjective interpretation. It resembles deciphering hieroglyphs through the haze of intoxication; while the essence may be discerned, the finer details remain obscured.

Imagine this: Herodotus, the original chronicler, striding through ancient Greece with an air of ownership, weaving narratives of deities, monsters, and drama rivaling the climax of "Keeping Up with the Spartans." Skip ahead a few millennia, and Howard Zinn detonates truth bombs like confetti at a rebellion-themed soirée, unsettling historical narratives akin to a bartender vigorously shaking a cocktail.

Yet, let's delve into revisionism, shall we? It's akin to hitting the "undo" button on history's greatest hits compilation. Consider Native American history: once relegated to footnotes by those viewing Columbus as merely a geographically befuddled Italian, it now basks in the limelight. Thanks to movements like the American Indian Movement and voices like Vine Deloria Jr., a fresh perspective emerges that refuses to gloss over centuries of oppression akin to a poor Tinder profile.

Historiography is not merely about stirring the pot but infusing zest into an otherwise bland concoction. Think of it as a culinary experiment gone deliciously awry, with historians tossing in new ingredients akin to contestants on "Chopped: Ancient Civilizations Edition." Case in point: the Dead Sea Scrolls. Forget Indiana Jones; these artifacts are true treasures, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the lives of ancient Essenes and igniting debates fiercer than a chili-eating contest.

However, let's not deceive ourselves; historiography harbors biases like street vendors peddling counterfeit wares. Recall the Cold War-era scholars who perceived communists lurking behind every corner. It turns out that impartiality wasn't their forte. And the Nazi propaganda machine? It churned out historical narratives akin to Goebbels-approved bedtime tales.

In today's era of misinformation and alternative truths, historiography assumes unprecedented significance. It is the antidote to historical forgetfulness, the shield against cognitive lethargy. By acknowledging our biases and scrutinizing the narratives we ingest, we inch closer to an honest comprehension of the past—one that confronts human existence's messy, intricate reality. So here's to historiography, the unsung hero of the annals. Without it, we'd flounder in a sea of half-truths and falsehoods, destined to replay the errors of yesteryears like a broken record. Here's to reshaping history, one revision at a time.

THE RUNDOWN

- Historiography, the study of history, helps us understand past mysteries.

- Like history, historiography changes over time, shaping how we see the past.

- Ancient and modern historians offer different perspectives on historical events.

- The internet changed how we research history, making information easier to find.

- "Revisionist" approaches challenge biased views, like rethinking Native American history.

- Historians uncover hidden treasures, like the enlightening Dead Sea Scrolls.

STATE OF THE UNION

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- COMING SOON

READING

Carnes, Chapter 25: From “Normalcy” to Economic Collapse: 1921-1933

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

Carnes, Chapter 25: From “Normalcy” to Economic Collapse: 1921-1933

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... These German bombings were very small compared with the British and American bombings of German cities. In January 1943 the Allies met at Casablanca and agreed on large-scale air attacks to achieve 'the destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and

economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to the point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.' And so, the saturation bombing of German cities began-with thousand -plane raids on Cologne, Essen, Frankfurt, Hamburg. The English flew at night with no pretense of aiming at 'military' targets; the Americans flew in the daytime and pretended precision, but bombing from high altitudes made that impossible. The climax of this terror bombing was the bombing of Dresden in early 1945, in which the tremendous heat generated by the bombs created a vacuum into which fire leaped swiftly in a great firestorm through the city. More than 100,000 died in Dresden. (Winston Churchill, in his wartime memoirs, confined himself to this account of the incident: 'We made a heavy raid in the latter month on Dresden, then a center of communication of Germany's Eastern Front') The bombing of Japanese cities continued the strategy of saturation bombing to destroy civilian morale; one nighttime fire-bombing of Tokyo took 80,000 lives. And then, on August 6, 1945, came the lone American plane in the sky over Hiroshima, dropping the first atomic bomb, leaving perhaps 100,000 Japanese dead, and tens of thousands more slowly dying from radiation poisoning. Twelve U.S. navy fliers in the Hiroshima city jail were killed in the bombing, a fact that the U.S. government has never officially acknowledged, according to historian Martin Sherwin (A World Destroyed). Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, with perhaps 50,000 killed. The justification for these atrocities was that this would end the war quickly, making unnecessary an invasion of Japan. Such an invasion would cost a huge number of lives, the government said-a million, according to Secretary of State Byrnes; half a million, Truman claimed was the figure given him by General George Marshall. (When the papers of the Manhattan Project-the project to build the atom bomb- were released years later, they showed that Marshall urged a warning to the Japanese about the bomb, so people could be removed and only military targets hit.) These estimates of invasion losses were not realistic, and seem to have been pulled out of the air to justify bombings which, as their effects became known, horrified more and more people. Japan, by August 1945, was in desperate shape and ready to surrender..."

"... These German bombings were very small compared with the British and American bombings of German cities. In January 1943 the Allies met at Casablanca and agreed on large-scale air attacks to achieve 'the destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and

economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to the point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.' And so, the saturation bombing of German cities began-with thousand -plane raids on Cologne, Essen, Frankfurt, Hamburg. The English flew at night with no pretense of aiming at 'military' targets; the Americans flew in the daytime and pretended precision, but bombing from high altitudes made that impossible. The climax of this terror bombing was the bombing of Dresden in early 1945, in which the tremendous heat generated by the bombs created a vacuum into which fire leaped swiftly in a great firestorm through the city. More than 100,000 died in Dresden. (Winston Churchill, in his wartime memoirs, confined himself to this account of the incident: 'We made a heavy raid in the latter month on Dresden, then a center of communication of Germany's Eastern Front') The bombing of Japanese cities continued the strategy of saturation bombing to destroy civilian morale; one nighttime fire-bombing of Tokyo took 80,000 lives. And then, on August 6, 1945, came the lone American plane in the sky over Hiroshima, dropping the first atomic bomb, leaving perhaps 100,000 Japanese dead, and tens of thousands more slowly dying from radiation poisoning. Twelve U.S. navy fliers in the Hiroshima city jail were killed in the bombing, a fact that the U.S. government has never officially acknowledged, according to historian Martin Sherwin (A World Destroyed). Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, with perhaps 50,000 killed. The justification for these atrocities was that this would end the war quickly, making unnecessary an invasion of Japan. Such an invasion would cost a huge number of lives, the government said-a million, according to Secretary of State Byrnes; half a million, Truman claimed was the figure given him by General George Marshall. (When the papers of the Manhattan Project-the project to build the atom bomb- were released years later, they showed that Marshall urged a warning to the Japanese about the bomb, so people could be removed and only military targets hit.) These estimates of invasion losses were not realistic, and seem to have been pulled out of the air to justify bombings which, as their effects became known, horrified more and more people. Japan, by August 1945, was in desperate shape and ready to surrender..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... Experiments with splitting the atom had taken place in England in 1932, and by the time Hitler invaded Poland, most of the world’s scientists understood that a man-made atomic explosion could be accomplished. How long before the actual fabrication of such a device could occur, however, no one knew. Roosevelt had already received a letter from one of the world’s leading pacifists, Albert Einstein, urging him to build a uranium bomb before the Nazis did. FDR set up a Uranium Committee in October 1939, which gained momentum less than a year later when British scientists, fearing their island might fall to the Nazis, arrived in America with a black box containing British atomic secrets. After mid-1941, when it was established, the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), headed by Vannevar Bush, was investigating the bomb’s feasibility.

Kept out of the loop by Bush, who feared he was a security risk, Einstein used his influence to nudge FDR toward the bomb project. Recent evidence suggests Einstein’s role in bringing the problem to Roosevelt’s attention was even greater than previously thought. Ironically, as Einstein’s biographer has pointed out, without the genius’s support, the bombs would have been built anyway, but not in time for use against Japan. Instead, with civilian and military authorities insufficiently aware of the vast destructiveness of such weapons in real situations, they may well have been used in Korea, at a time when the Soviet Union would have had its own bombs for counterattack, thus offering the terrifying possibility of a nuclear conflict over Korea. By wielding his considerable influence in 1939 and 1940, Einstein may have saved innumerable lives, beyond those of the Americans and Japanese who would have clashed in Operation Olympic, the invasion of the Japanese home islands.

No one knew the status of Hitler’s bomb project—only that there was one. As late as 1944, American intelligence was still seeking to assassinate Walter Heisenberg (head of the Nazi bomb project), among others, unaware at the time that the German bomb was all but kaput. In total secrecy, then, the Manhattan Project, placed under the U.S. Army’s Corps of Engineers and begun in the Borough of Manhattan, was directed by a general, Leslie Groves, a man with an appreciation for the fruits of capitalism. He scarcely blinked at the incredible demands for material, requiring thousands of tons of silver for wiring, only to be told, 'In the Treasury [Department] we do not speak of tons of silver. Our unit is the troy ounce.' Yet Groves got his silver and everything else he required. Roosevelt made sure the Manhattan Project lacked for nothing, although Roosevelt himself died before seeing the terrible fruition of the Manhattan Project’s deadly labors..."

"... Experiments with splitting the atom had taken place in England in 1932, and by the time Hitler invaded Poland, most of the world’s scientists understood that a man-made atomic explosion could be accomplished. How long before the actual fabrication of such a device could occur, however, no one knew. Roosevelt had already received a letter from one of the world’s leading pacifists, Albert Einstein, urging him to build a uranium bomb before the Nazis did. FDR set up a Uranium Committee in October 1939, which gained momentum less than a year later when British scientists, fearing their island might fall to the Nazis, arrived in America with a black box containing British atomic secrets. After mid-1941, when it was established, the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), headed by Vannevar Bush, was investigating the bomb’s feasibility.

Kept out of the loop by Bush, who feared he was a security risk, Einstein used his influence to nudge FDR toward the bomb project. Recent evidence suggests Einstein’s role in bringing the problem to Roosevelt’s attention was even greater than previously thought. Ironically, as Einstein’s biographer has pointed out, without the genius’s support, the bombs would have been built anyway, but not in time for use against Japan. Instead, with civilian and military authorities insufficiently aware of the vast destructiveness of such weapons in real situations, they may well have been used in Korea, at a time when the Soviet Union would have had its own bombs for counterattack, thus offering the terrifying possibility of a nuclear conflict over Korea. By wielding his considerable influence in 1939 and 1940, Einstein may have saved innumerable lives, beyond those of the Americans and Japanese who would have clashed in Operation Olympic, the invasion of the Japanese home islands.

No one knew the status of Hitler’s bomb project—only that there was one. As late as 1944, American intelligence was still seeking to assassinate Walter Heisenberg (head of the Nazi bomb project), among others, unaware at the time that the German bomb was all but kaput. In total secrecy, then, the Manhattan Project, placed under the U.S. Army’s Corps of Engineers and begun in the Borough of Manhattan, was directed by a general, Leslie Groves, a man with an appreciation for the fruits of capitalism. He scarcely blinked at the incredible demands for material, requiring thousands of tons of silver for wiring, only to be told, 'In the Treasury [Department] we do not speak of tons of silver. Our unit is the troy ounce.' Yet Groves got his silver and everything else he required. Roosevelt made sure the Manhattan Project lacked for nothing, although Roosevelt himself died before seeing the terrible fruition of the Manhattan Project’s deadly labors..."

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"... In 1957 East German authorities responded to the youth rebellion with justified despair for the future of Communism. Alfred Kurella, head of the new Commission for Culture in the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party (the ruling, Soviet-controlled party in the GDR), warned of the “danger of growing decadent influences” that were spurring the 'animalistic element' in East German youth. Kurella announced that it was time for good Communists to 'save the cultural and social life of the … nation from this destruction' and to preserve 'the true national culture.' The party’s Culture Conference in October 1957 declared that in recent years 'damaging influences of the Western capitalist nonculture' had 'penetrated' the GDR. By the following year, rock-and-roll had replaced jazz as the most dangerous of Western cultural products. In a 1958 announcement on rock, General Secretary Walter Ulbricht condemned 'its noise' as an 'expression of impetuosity' that characterized the “anarchism of capitalist society.' Defense Minister Willi Stoph distributed a warning, published in East German newspapers, that 'rock ’n’ roll was a means of seduction to make the youth ripe for atomic war.' Stoph singled out Bill Haley and the Comets, who had toured West Germany in 1958. 'It was Haley’s mission,' Stoph said, 'to engender fanatical, hysterical enthusiasm among German youth and lead them into a mass grave with rock & roll.' State-run newspapers broadcast these warnings. Neues Deutschland called Elvis Presley a 'Cold War Weapon,' and Junge Welt counseled its young readers, 'Those persons plotting an atomic war are making a fuss about Presley because they know youths dumb enough to become Presley fans are dumb enough to fight in the war.'..."

"... In 1957 East German authorities responded to the youth rebellion with justified despair for the future of Communism. Alfred Kurella, head of the new Commission for Culture in the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party (the ruling, Soviet-controlled party in the GDR), warned of the “danger of growing decadent influences” that were spurring the 'animalistic element' in East German youth. Kurella announced that it was time for good Communists to 'save the cultural and social life of the … nation from this destruction' and to preserve 'the true national culture.' The party’s Culture Conference in October 1957 declared that in recent years 'damaging influences of the Western capitalist nonculture' had 'penetrated' the GDR. By the following year, rock-and-roll had replaced jazz as the most dangerous of Western cultural products. In a 1958 announcement on rock, General Secretary Walter Ulbricht condemned 'its noise' as an 'expression of impetuosity' that characterized the “anarchism of capitalist society.' Defense Minister Willi Stoph distributed a warning, published in East German newspapers, that 'rock ’n’ roll was a means of seduction to make the youth ripe for atomic war.' Stoph singled out Bill Haley and the Comets, who had toured West Germany in 1958. 'It was Haley’s mission,' Stoph said, 'to engender fanatical, hysterical enthusiasm among German youth and lead them into a mass grave with rock & roll.' State-run newspapers broadcast these warnings. Neues Deutschland called Elvis Presley a 'Cold War Weapon,' and Junge Welt counseled its young readers, 'Those persons plotting an atomic war are making a fuss about Presley because they know youths dumb enough to become Presley fans are dumb enough to fight in the war.'..."

What Does Professor Lancaster Think?

The atomic bomb. The Pandora's box of modern conflict unleashed with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer blow. It prompts one to question if humanity's collective intelligence is but a hair's breadth from single digits. Imagine the scene: 1939. Albert Einstein, the iconic figure of genius with a perpetual case of bedhead, dispatches a letter to President Roosevelt akin to a celestial courier service. Instead of a parcel, it bears a grave warning about Nazi Germany delving into atomic endeavors. Thus, the Manhattan Project commences, veiled in secrecy rivaling the enigma of Area 51's extraterrestrial recipes.

Fast forward to August 1945. Like a child brandishing a new plaything, Uncle Sam opts to flaunt his gleaming innovation to Japan. What better display of military might than raining atomic devastation upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Cue the mushroom clouds, the fallout of radiation, and an overwhelming sense of existential dread. The discourse persists like a broken record caught in a loop. On one side, proponents cheer, citing the nuking of Japan as a savior of Allied lives and an expediter of World War II's conclusion. Yet, on the opposing end, critics wag fingers, aghast at the bombings as monumental war crimes.

Let's not overlook Dresden, the forgotten tragedy sandwiched between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, like the uneasy middle child at a dysfunctional family gathering. The Allies, in a particularly trigger-happy state, opted to incinerate the German city in 1945, leaving behind a desolate landscape and a hefty invoice for PTSD treatment. What's the lesson amidst this grim narrative? Primarily, it's an immersion in the convoluted morality of warfare. It appears that when confronted with the specter of mushroom clouds, moral compasses spin wildly, akin to a GPS in a blackout.

Nevertheless, amid the wreckage and radioactive fallout, a glimmer of hope persists—a testament to humanity's resilience amidst its darkest hours. Here's to the survivors, the overlooked heroes of history's bleakest chapters, and the defiant rebels who refuse to let tyrants silence their rhythm. Ultimately, the atomic bomb is not solely a cautionary tale; it's a reflection of humanity's capacity for both annihilation and redemption. Whether embraced or rejected, it remains a narrative, one mushroom cloud at a time. So, fasten your seatbelts, for the journey ahead promises turbulence.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The atomic bomb. The Pandora's box of modern conflict unleashed with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer blow. It prompts one to question if humanity's collective intelligence is but a hair's breadth from single digits. Imagine the scene: 1939. Albert Einstein, the iconic figure of genius with a perpetual case of bedhead, dispatches a letter to President Roosevelt akin to a celestial courier service. Instead of a parcel, it bears a grave warning about Nazi Germany delving into atomic endeavors. Thus, the Manhattan Project commences, veiled in secrecy rivaling the enigma of Area 51's extraterrestrial recipes.

Fast forward to August 1945. Like a child brandishing a new plaything, Uncle Sam opts to flaunt his gleaming innovation to Japan. What better display of military might than raining atomic devastation upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Cue the mushroom clouds, the fallout of radiation, and an overwhelming sense of existential dread. The discourse persists like a broken record caught in a loop. On one side, proponents cheer, citing the nuking of Japan as a savior of Allied lives and an expediter of World War II's conclusion. Yet, on the opposing end, critics wag fingers, aghast at the bombings as monumental war crimes.

Let's not overlook Dresden, the forgotten tragedy sandwiched between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, like the uneasy middle child at a dysfunctional family gathering. The Allies, in a particularly trigger-happy state, opted to incinerate the German city in 1945, leaving behind a desolate landscape and a hefty invoice for PTSD treatment. What's the lesson amidst this grim narrative? Primarily, it's an immersion in the convoluted morality of warfare. It appears that when confronted with the specter of mushroom clouds, moral compasses spin wildly, akin to a GPS in a blackout.

Nevertheless, amid the wreckage and radioactive fallout, a glimmer of hope persists—a testament to humanity's resilience amidst its darkest hours. Here's to the survivors, the overlooked heroes of history's bleakest chapters, and the defiant rebels who refuse to let tyrants silence their rhythm. Ultimately, the atomic bomb is not solely a cautionary tale; it's a reflection of humanity's capacity for both annihilation and redemption. Whether embraced or rejected, it remains a narrative, one mushroom cloud at a time. So, fasten your seatbelts, for the journey ahead promises turbulence.

THE RUNDOWN

- The atomic bomb, like a Pandora's box, was a huge, dangerous discovery during war.

- In 1939, Einstein warned America about Nazi Germany's atomic plans, leading to the secret Manhattan Project.

- In 1945, America used the bomb on Japan, causing massive destruction and fear.

- Some people think it saved lives and ended the war, while others call it a horrible crime.

- Dresden, a city in Germany, was also destroyed by Allied bombs in 1945.

- The atomic bomb shows how war can make people do terrible things, but it also shows human strength and hope.

QUESTIONS

- What were the key factors that prompted the development of the atomic bomb during World War II? How did the Manhattan Project play a role in this development?

- Discuss the ethical considerations surrounding the decision to use atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Do you believe the bombings were justified? Why or why not?

- What impact did the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have on subsequent international relations and conflicts? How did it shape the world's perception of nuclear weapons?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

Amidst the vibrant glow of post-war America, pulsating with promises of prosperity and tinged with the scent of anxiety, a delicate balance hung between hope and apprehension. It was an era of chain-smoking men in suits and women whose aspirations were as meticulously groomed as their hairdos. Yet, beneath the surface of suburban tranquility, the world teetered on the brink of chaos. The West, towering confidently like a skyscraper, intoxicated by recent triumphs, and the East, a brooding giant draped in the fervor of revolution, eyes ablaze with ideological zeal.

Let us not overlook the forgotten souls etched into the fractured streets of Berlin, overshadowed by narratives of triumph. Behind the Iron Curtain, countless individuals suffered under Soviet oppression, their dreams crushed in the name of equality, their only freedom, the right to vanish. Then came the bomb—the climax of humanity's dark comedy. Its blinding flash and devastating impact ushered in the atomic age, blurring the lines between friend and foe. Amidst the uncertainty, a strange unity emerged—a recognition that we were all players in life's absurd theater regardless of affiliation.

Amidst the vibrant glow of post-war America, pulsating with promises of prosperity and tinged with the scent of anxiety, a delicate balance hung between hope and apprehension. It was an era of chain-smoking men in suits and women whose aspirations were as meticulously groomed as their hairdos. Yet, beneath the surface of suburban tranquility, the world teetered on the brink of chaos. The West, towering confidently like a skyscraper, intoxicated by recent triumphs, and the East, a brooding giant draped in the fervor of revolution, eyes ablaze with ideological zeal.

Let us not overlook the forgotten souls etched into the fractured streets of Berlin, overshadowed by narratives of triumph. Behind the Iron Curtain, countless individuals suffered under Soviet oppression, their dreams crushed in the name of equality, their only freedom, the right to vanish. Then came the bomb—the climax of humanity's dark comedy. Its blinding flash and devastating impact ushered in the atomic age, blurring the lines between friend and foe. Amidst the uncertainty, a strange unity emerged—a recognition that we were all players in life's absurd theater regardless of affiliation.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- 1941 Japanese planes attack Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. United States enters World War II.

- 1942 Order 9066

- 1942 The Manhattan Project / Atomic Bomb

- 1944 Fort Ontario

- The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- 1939 Apple Pie

- 1939 Technicolor

- 1940- Fashion

- 1940 R & B Music

- 1942 Bracero Program

- 1943 Zoot Suit Riots

- 1943 Nachos

- 1943 Pizza

- 1945 Operation Paperclip

- 1945: Television is born

- 1947 Jackie Robinson

- 1948 President Truman Orders Racial Equality in the Military

- 1948 Sexual Behavior in the Human Male

- Perez v. Sharp

- 1949 George Orwell

- 1949 The Fairness Doctrine

- 1950-53 Korean War

- 1950- Fashion

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity: Debate on America's Role in World War II and its Aftermath

Objective: Participate in a structured debate to explore and understand different viewpoints on America's involvement in World War II and its impact from 1939 to 1950.

Instructions:

Classroom: "Gallery Walk"

Select Themes:

Introduction (5 minutes):

Google Doc Creation (20-30 minutes):

Virtual Museum Tour (20-30 minutes):

Discussion and Analysis (20-30 minutes):

Reflection (5 minutes):

Additional Tips:

Activity: Debate on America's Role in World War II and its Aftermath

Objective: Participate in a structured debate to explore and understand different viewpoints on America's involvement in World War II and its impact from 1939 to 1950.

Instructions:

- Divide the class into two groups: "Proponents" and "Opponents."

- Assign roles within your group, such as historians, policymakers, soldiers, civilians, etc.

- Research and prepare arguments supporting or opposing America's involvement in World War II and its aftermath.

- Present your group's opening arguments, clearly stating your position on America's role in World War II and its consequences.

- Use evidence to support your points.

- Challenge the arguments presented by the opposing group.

- Engage in cross-examination to probe deeper into their points.

- Participate in a moderated discussion with members from both groups.

- Listen actively and respond thoughtfully to the points raised.

- Ask questions to the debaters from the audience (non-participating students).

- Make sure your questions are insightful and relevant.

- Deliver your group's closing statements, summarizing your position and emphasizing key arguments.

- Keep your conclusions clear and persuasive.

- This debate activity offers you a chance to explore diverse perspectives on America's involvement in World War II and its impact. By participating actively and engaging with historical viewpoints, you'll develop critical thinking skills and gain a deeper insight into this pivotal period in US history.

Classroom: "Gallery Walk"

Select Themes:

- Identify key themes or topics relevant to US history between 1939 and 1950. This could include World War II, the Great Depression, social changes, technological advancements, etc.

- Instead of physical materials, gather digital resources such as primary source documents, photographs, political cartoons, newspaper articles, excerpts from speeches, and other relevant materials. Utilize reputable online archives, museum websites, digital libraries, and educational platforms.

- Assign each theme or topic to a group of students. Instruct each group to compile relevant online resources into a shared Google Doc. They should organize the materials in an organized manner within the document.

Introduction (5 minutes):

- Begin the activity by providing a brief overview of the time period and explaining the purpose of creating a virtual museum. Emphasize the importance of analyzing primary sources to gain insight into historical events.

Google Doc Creation (20-30 minutes):

- Divide the class into small groups, with each group responsible for a specific theme or topic.

- Instruct each group to create a Google Doc and share it with all group members.

- Assign tasks within each group, such as researching, summarizing, and organizing the online resources into the Google Doc.

- Encourage students to collaborate effectively and ensure that the document is well-structured and visually appealing.

Virtual Museum Tour (20-30 minutes):

- Once the Google Docs are completed, provide time for each group to present their virtual museum to the class.

- Instruct students to navigate through the shared Google Docs, exploring the online resources compiled by their peers.

- Encourage students to engage with the content, ask questions, and provide feedback to their classmates.

Discussion and Analysis (20-30 minutes):

- Reconvene the class in a virtual meeting room or discussion board.

- Facilitate a whole-group discussion to reflect on the virtual museum tour.

- Encourage students to share their observations, insights, and questions about the online resources presented by their peers.

- Guide the discussion to help students make connections between the different themes and events of the time period.

Reflection (5 minutes):

- Conclude the activity by asking students to reflect individually or in small groups on what they learned from creating and exploring the virtual museums.

- Have students consider how the online primary sources provided a deeper understanding of US history during the specified time frame.

Additional Tips:

- Provide guidelines and templates for the Google Docs to ensure consistency and clarity across the virtual museums.

- Encourage students to include multimedia elements such as images, videos, and hyperlinks within their Google Docs to enhance the presentation.

- Facilitate peer review sessions where students can provide constructive feedback on each other's virtual museums before the presentation.

- Follow up the activity with a related online assignment or discussion forum to reinforce key concepts and allow for further exploration of the time period.

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

The tangled web we weave when history decides to play dice with fate. Between the chaotic dance of triumph and the somber dirge of tragedy, America stumbled through the years like a drunken sailor on a stormy sea, unsure whether to toast victory or drown sorrows in cheap bourbon.

Uncle Sam, clad in his star-spangled attire, descends onto the global stage resembling an amplified Captain America, poised to vanquish the forces of Nazism and etch his name in heroic annals. World War II unfolds as America's cinematic spectacle, replete with detonations, valorous sacrifices, and an anthem of liberty reverberating through the atmosphere. However, just as the nation appeared adorned in the gleaming armor of righteousness, it stumbled, detaining swathes of innocents merely for their resemblance to the Japanese. Could you call the abrupt stop?

The internment camps, where the sanctity of constitutional rights languished in a gradual and agonizing demise. Families sundered, aspirations shattered—all under the guise of national security. For what better signifies "freedom" than corralling one's populace and subjecting them to the treatment befitting foes?

Nevertheless, amidst the shadows, Truman, in a gesture of commendable sincerity, deemed segregation within the military as antiquated as a mullet at a modernist gathering, thus affixing his signature to its cessation. Progress, albeit belated! It took society a while to embrace the notion of egalitarian treatment irrespective of skin hue, yet tardy better than never, correct?

Yet, just as the tendrils of optimism began to coil around societal progress, McCarthy barged in like an inebriated reveler on a rampage. Suddenly, everyone metamorphosed into a communist threat, and the mere sniffle in the direction of Marx's manifesto warranted exile to Siberia. It resembled the Salem witch trials, albeit with less sorcery and more crimson hysteria.

But lo, amidst this maelstrom of madness, the United Nations emerged—a flicker of hope amid the chaos. For what exudes harmony more than nations convening to reconcile differences sans recourse to nuclear obliteration? It parallels a discordant familial gathering, yet with diplomats in lieu of passive-aggressive remarks concerning Aunt Mildred's culinary creations.

And regarding nuclear Armageddon, let us not forsake the perennial ethical quandary: the atomic bomb. Indeed, it concluded the conflict with a resounding crescendo, yet at what moral expense? The towering plumes over Hiroshima and Nagasaki cast a lingering pall upon our ethical fabric, compelling us to grapple with the ramifications of playing deity with geopolitical destinies.

Thus, we find ourselves ensnared amid triumphs and tribulations, strides forward and retrogressions. It's an exhilarating odyssey, albeit fraught with peril. Nevertheless, we persevere. Let us raise a glass to yesteryears, salute to tomorrow, and aspire to that perchance. Just perchance, we unravel this enigma as we court our demise. Salutations, America. Here's to the pandemonium.

Or in other words:

The tangled web we weave when history decides to play dice with fate. Between the chaotic dance of triumph and the somber dirge of tragedy, America stumbled through the years like a drunken sailor on a stormy sea, unsure whether to toast victory or drown sorrows in cheap bourbon.

Uncle Sam, clad in his star-spangled attire, descends onto the global stage resembling an amplified Captain America, poised to vanquish the forces of Nazism and etch his name in heroic annals. World War II unfolds as America's cinematic spectacle, replete with detonations, valorous sacrifices, and an anthem of liberty reverberating through the atmosphere. However, just as the nation appeared adorned in the gleaming armor of righteousness, it stumbled, detaining swathes of innocents merely for their resemblance to the Japanese. Could you call the abrupt stop?

The internment camps, where the sanctity of constitutional rights languished in a gradual and agonizing demise. Families sundered, aspirations shattered—all under the guise of national security. For what better signifies "freedom" than corralling one's populace and subjecting them to the treatment befitting foes?

Nevertheless, amidst the shadows, Truman, in a gesture of commendable sincerity, deemed segregation within the military as antiquated as a mullet at a modernist gathering, thus affixing his signature to its cessation. Progress, albeit belated! It took society a while to embrace the notion of egalitarian treatment irrespective of skin hue, yet tardy better than never, correct?

Yet, just as the tendrils of optimism began to coil around societal progress, McCarthy barged in like an inebriated reveler on a rampage. Suddenly, everyone metamorphosed into a communist threat, and the mere sniffle in the direction of Marx's manifesto warranted exile to Siberia. It resembled the Salem witch trials, albeit with less sorcery and more crimson hysteria.

But lo, amidst this maelstrom of madness, the United Nations emerged—a flicker of hope amid the chaos. For what exudes harmony more than nations convening to reconcile differences sans recourse to nuclear obliteration? It parallels a discordant familial gathering, yet with diplomats in lieu of passive-aggressive remarks concerning Aunt Mildred's culinary creations.

And regarding nuclear Armageddon, let us not forsake the perennial ethical quandary: the atomic bomb. Indeed, it concluded the conflict with a resounding crescendo, yet at what moral expense? The towering plumes over Hiroshima and Nagasaki cast a lingering pall upon our ethical fabric, compelling us to grapple with the ramifications of playing deity with geopolitical destinies.

Thus, we find ourselves ensnared amid triumphs and tribulations, strides forward and retrogressions. It's an exhilarating odyssey, albeit fraught with peril. Nevertheless, we persevere. Let us raise a glass to yesteryears, salute to tomorrow, and aspire to that perchance. Just perchance, we unravel this enigma as we court our demise. Salutations, America. Here's to the pandemonium.

Or in other words:

- America treads uncertain waters between triumph and tragedy, celebrating victories and drowning sorrows.

- World War II paints America as a heroic figure, yet the internment of innocent Japanese-Americans tarnishes this image.

- Truman's abolition of military segregation marks progress, albeit overdue, in the fight for equality.

- McCarthyism casts a shadow of fear, turning Americans against each other in a frenzy of communist paranoia.

- The birth of the United Nations offers a glimmer of hope amid global chaos, promoting diplomacy over destruction.

- The moral quandary of the atomic bomb leaves a haunting legacy, reminding us of the consequences of playing with fate.

ASSIGNMENTS

Need help with the Final Thesis? Click HERE for the rundown!

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #8

Wisecrack is a US-American film, and video production company founded in 2014 and produces various web series and podcasts such as Thug Notes, Earthling Cinema, and 8-Bit Philosophy. The group focuses on analyzing anime, film, literature, and video games, drawing out philosophy, sociology, psychology, and other meanings that we can interpret from media. Watch this short video on fascism and answer the following questions:

- Forum Discussion #8

- FINAL THESIS

Need help with the Final Thesis? Click HERE for the rundown!

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #8

Wisecrack is a US-American film, and video production company founded in 2014 and produces various web series and podcasts such as Thug Notes, Earthling Cinema, and 8-Bit Philosophy. The group focuses on analyzing anime, film, literature, and video games, drawing out philosophy, sociology, psychology, and other meanings that we can interpret from media. Watch this short video on fascism and answer the following questions:

Would you consider former President Trump a fascist, in the vein of Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini? Why or why not? Use real-world examples from World War II in your response.

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

In a society where the term "fascist" is tossed around as casually as ordering a frappuccino at Starbucks, it's crucial to pause and truly understand its weight. While it's tempting to label anyone with disagreeable politics as such, fascism's roots are deep, stretching back to ancient Rome's "fasces," symbolizing strength through unity. Umberto Eco, the Italian writer, characterized fascism not as a monolithic evil but as a dysfunctional family dynamic, outlining fourteen traits, including hyper-nationalism and disdain for human rights. Yet, by overusing "fascist," we risk diminishing its significance, akin to falsely crying wolf in a world of imitation fascists. We must safeguard the term for genuine threats, as when actual fascism emerges, we can't afford to be unprepared. So, before hastily applying the label, let's reflect: are they genuinely advancing towards totalitarianism or just a nuisance? In a world where words hold power, fascism isn't just a buzzword—it's a chilling reality that requires clear-eyed confrontation.

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

In a society where the term "fascist" is tossed around as casually as ordering a frappuccino at Starbucks, it's crucial to pause and truly understand its weight. While it's tempting to label anyone with disagreeable politics as such, fascism's roots are deep, stretching back to ancient Rome's "fasces," symbolizing strength through unity. Umberto Eco, the Italian writer, characterized fascism not as a monolithic evil but as a dysfunctional family dynamic, outlining fourteen traits, including hyper-nationalism and disdain for human rights. Yet, by overusing "fascist," we risk diminishing its significance, akin to falsely crying wolf in a world of imitation fascists. We must safeguard the term for genuine threats, as when actual fascism emerges, we can't afford to be unprepared. So, before hastily applying the label, let's reflect: are they genuinely advancing towards totalitarianism or just a nuisance? In a world where words hold power, fascism isn't just a buzzword—it's a chilling reality that requires clear-eyed confrontation.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.