HST 202 Module #3

Contents May Have Shifted (1899 CE - 1914 CE)

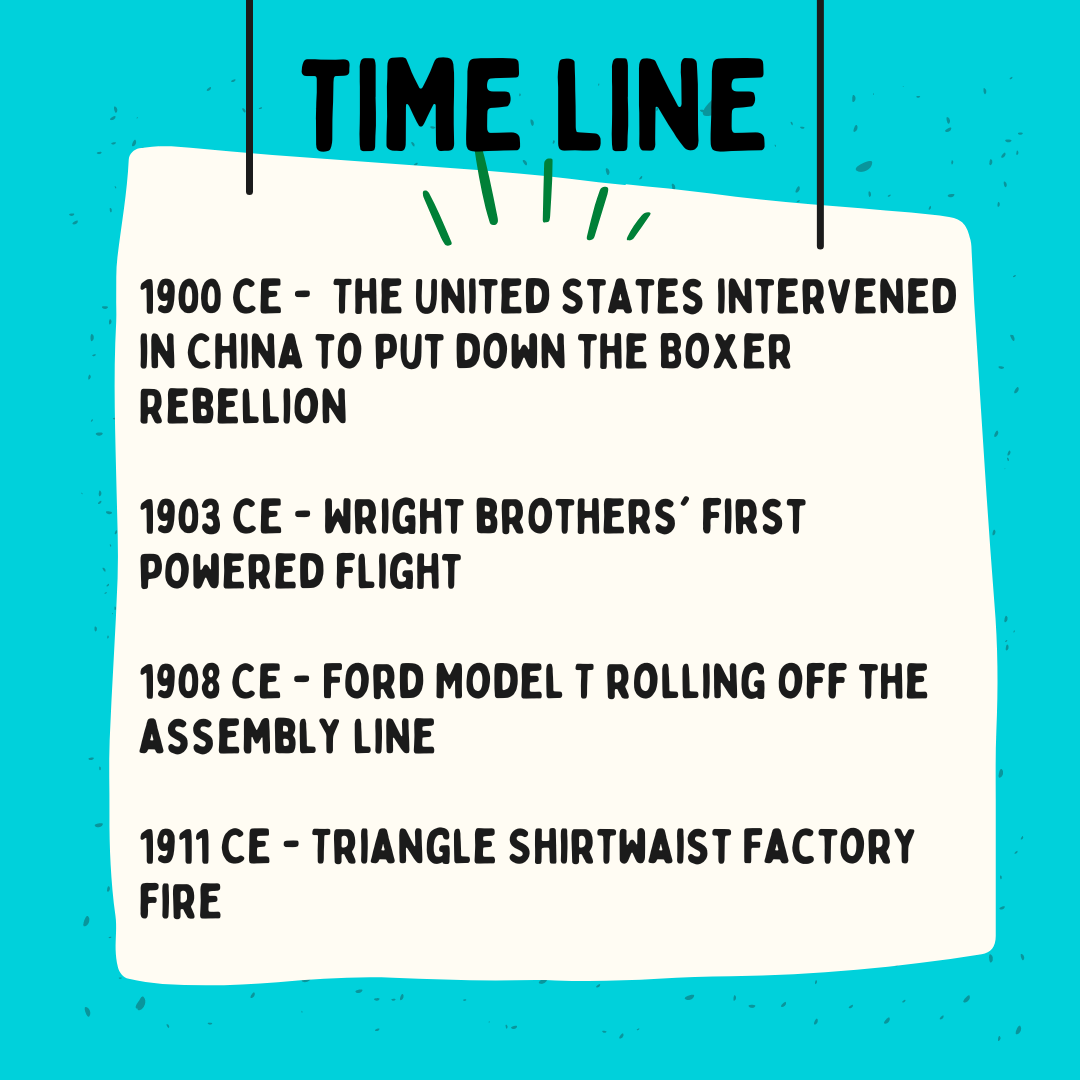

The early 20th century was when the nation underwent substantial growth, akin to a teenager experiencing a growth spurt. The Industrial Revolution marked the era as a transformative time as if America collectively transitioned through adolescence, acquired a car, and simultaneously uncovered the wonders of rock 'n' roll. Consider it a maturation saga, with abundant industrial progress and a conspicuous absence of teenage melodrama.

I just wanted to clarify: the advantages of industrial and urban expansion were evident. The shift from horse-drawn carriages to assembly lines was swifter than one could fathom. The economy flourished, job opportunities mushroomed, and innovation took center stage. The assembly line streamlined production, morphing factories into the predecessors of fast-food establishments—except the offerings were constructed from steel, not edible items.

However, this surge came at a cost. The laborers in those factories endured conditions harsher than a sitcom character trapped in a relentless laugh track. Prolonged working hours, meager wages, and perilous workplaces would trigger an OSHA frenzy if it existed then. Urbanization presented its challenges – envision overcrowded slums and sanitation so deplorable that a hazmat suit would be a prerequisite for a casual stroll.

Let's not overlook the widening chasm between the affluent and the impoverished. It resembled a dance craze where the class struggle took center stage, captivating everyone's attention. Social tensions skyrocketed, akin to a hipster's blood pressure at a mainstream coffee shop.

Enter the Progressive Movement—the champions of social reform. Led by Teddy Roosevelt, these individuals aspired to rectify the chaos faster than a parent stumbling upon a teenager's concealed stash of questionable materials. They implemented regulations and established agencies like the FDA because, apparently, ingesting arsenic wasn't as enjoyable as it sounded.

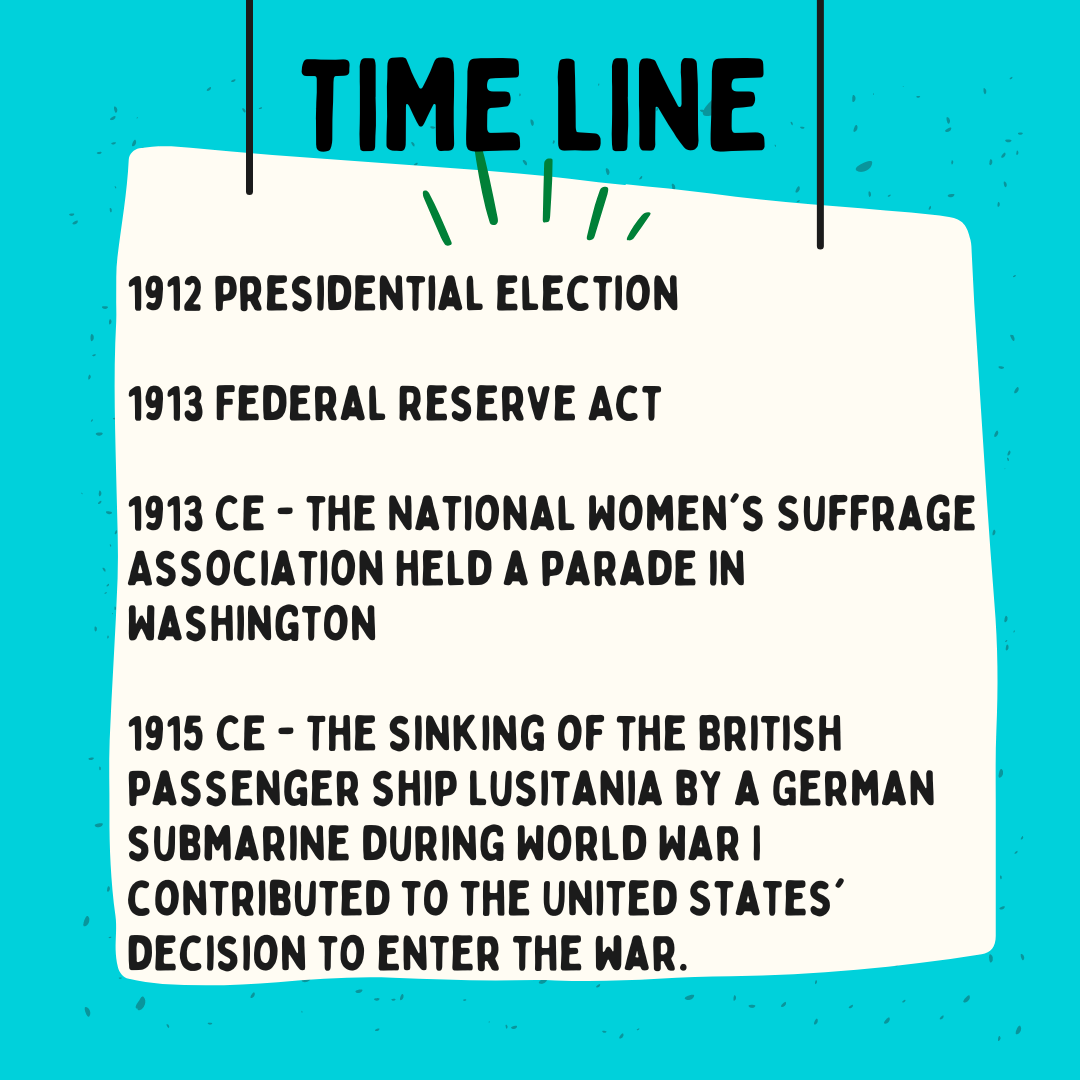

Then, there was the suffrage movement, where women fought tenaciously for the right to vote. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton played the roles of Thelma and Louise in the democracy narrative. The 19th Amendment served as their grand finale, compelling the political boys' club to make room for the ladies.

Simultaneously, the African American civil rights movement gained momentum, and the Great Migration transformed urban hubs into hubs of culture and ideas during the Harlem Renaissance. It resembled a cultural explosion, making the Roaring Twenties seem like a mere kitten's meow.

World War I? It's a plot twist no one anticipated. America eventually joined the war, akin to that friend swearing they'll stay in but showing up at the party anyway. The aftermath elevated the U.S. to a global player, only for the Senate to abruptly abandon the League of Nations, treating it like a regrettable Tinder date.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911? That stood as the tragic climax of our unfolding narrative. The loss of 146 lives in the flames cast a glaring light on the dark side of industrial growth. Nevertheless, every compelling story requires a catalyst for change, right? Reforms in labor and workplace safety ensued, underscoring that, sometimes, a fire is imperative to ignite progress. In this case, quite literally.

So, why does this saga from the early 20th century matter? It's akin to perusing old yearbook photos—cringe-worthy yet illuminating. The struggles and triumphs of that era served as the awkward teenage years that molded modern America. Valuable lessons were absorbed, and mistakes were made, providing us with a roadmap to navigate the complexities of our current predicament. Because, let's be honest, as much as things evolve, they also maintain a captivating degree of chaos, wonder, and absurdity.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The early 20th century was when the nation underwent substantial growth, akin to a teenager experiencing a growth spurt. The Industrial Revolution marked the era as a transformative time as if America collectively transitioned through adolescence, acquired a car, and simultaneously uncovered the wonders of rock 'n' roll. Consider it a maturation saga, with abundant industrial progress and a conspicuous absence of teenage melodrama.

I just wanted to clarify: the advantages of industrial and urban expansion were evident. The shift from horse-drawn carriages to assembly lines was swifter than one could fathom. The economy flourished, job opportunities mushroomed, and innovation took center stage. The assembly line streamlined production, morphing factories into the predecessors of fast-food establishments—except the offerings were constructed from steel, not edible items.

However, this surge came at a cost. The laborers in those factories endured conditions harsher than a sitcom character trapped in a relentless laugh track. Prolonged working hours, meager wages, and perilous workplaces would trigger an OSHA frenzy if it existed then. Urbanization presented its challenges – envision overcrowded slums and sanitation so deplorable that a hazmat suit would be a prerequisite for a casual stroll.

Let's not overlook the widening chasm between the affluent and the impoverished. It resembled a dance craze where the class struggle took center stage, captivating everyone's attention. Social tensions skyrocketed, akin to a hipster's blood pressure at a mainstream coffee shop.

Enter the Progressive Movement—the champions of social reform. Led by Teddy Roosevelt, these individuals aspired to rectify the chaos faster than a parent stumbling upon a teenager's concealed stash of questionable materials. They implemented regulations and established agencies like the FDA because, apparently, ingesting arsenic wasn't as enjoyable as it sounded.

Then, there was the suffrage movement, where women fought tenaciously for the right to vote. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton played the roles of Thelma and Louise in the democracy narrative. The 19th Amendment served as their grand finale, compelling the political boys' club to make room for the ladies.

Simultaneously, the African American civil rights movement gained momentum, and the Great Migration transformed urban hubs into hubs of culture and ideas during the Harlem Renaissance. It resembled a cultural explosion, making the Roaring Twenties seem like a mere kitten's meow.

World War I? It's a plot twist no one anticipated. America eventually joined the war, akin to that friend swearing they'll stay in but showing up at the party anyway. The aftermath elevated the U.S. to a global player, only for the Senate to abruptly abandon the League of Nations, treating it like a regrettable Tinder date.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911? That stood as the tragic climax of our unfolding narrative. The loss of 146 lives in the flames cast a glaring light on the dark side of industrial growth. Nevertheless, every compelling story requires a catalyst for change, right? Reforms in labor and workplace safety ensued, underscoring that, sometimes, a fire is imperative to ignite progress. In this case, quite literally.

So, why does this saga from the early 20th century matter? It's akin to perusing old yearbook photos—cringe-worthy yet illuminating. The struggles and triumphs of that era served as the awkward teenage years that molded modern America. Valuable lessons were absorbed, and mistakes were made, providing us with a roadmap to navigate the complexities of our current predicament. Because, let's be honest, as much as things evolve, they also maintain a captivating degree of chaos, wonder, and absurdity.

THE RUNDOWN

- Early 20th century: U.S. undergoes unprecedented industrial and urban growth. Economic prosperity, technological advancements, and urbanization redefine the nation.

- Deplorable working conditions, urban issues, and a widening wealth gap pose challenges. Progressive Movement emerges, advocating for political and social reforms.

- Suffrage movement secures women's right to vote with the 19th Amendment. African American civil rights gain momentum, fostering cultural and intellectual movements.

- U.S. enters the war, contributes to Allied victory, and emerges as a global power. Woodrow Wilson's vision shapes foreign policy but faces challenges in the Senate.

- Early 20th-century challenges offer insights into contemporary issues. Examining American values and global roles informs discussions on present-day challenges.

- Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire (1911) exposes hazardous working conditions. Public outcry leads to labor and workplace safety reforms, showcasing the power of tragic events.

QUESTIONS

- Explore the role of the Progressive Movement, led by Teddy Roosevelt, in addressing social issues and implementing reforms. How did regulations and agencies like the FDA contribute to positive change?

- Could you examine the suffrage movement and the fight for women's right to vote? How did individuals like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton contribute to this movement, and how did the 19th Amendment impact American democracy?

- Discuss the African American civil rights movement during the early 20th century and the transformative effects of the Great Migration on urban hubs, particularly during the Harlem Renaissance.

#3 Credit is Important

History is woven with the intricate threads of triumphs and tragedies, acts of heroism and unspeakable horrors, and the occasional individual who stumbled unwittingly into greatness while pursuing mundane objectives like locating misplaced car keys. It constitutes a tumultuous journey through the annals of time, where participants either secure their names in the eternal record or, more frequently, fade into obscurity, akin to the hazy memories of regrettable choices from the previous night. Let's delve into the imperative principle of ascribing due recognition. It mirrors the ethos of history – treating others' contributions with the same respect one would desire for their own. History often resembles a tabloid column composed by a discerning neighbor privy to everyone's affairs yet prone to misrepresenting the finer details.

Consider the Civil Rights Movement, an illustration of Martin Luther King Jr. basking in the spotlight like a Broadway diva. However, behind the scenes, an ensemble cast of predominantly female unsung heroes toiled tirelessly for justice. It's reminiscent of an Oscars ceremony, where everyone anticipates their moment, but the industry consistently neglects distributing well-deserved accolades. Then there's the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, an unsettling narrative of individuals, assuming they were enrolling in a health spa, unwittingly becoming subjects of an unethical experiment. If only their involuntary sacrifice garnered the acknowledgment it warranted, perhaps they would have preferred a spa day.

Now, let's scrutinize the convoluted DNA storyline. James Watson and Francis Crick bask in the glory of the Nobel Prize for unraveling the DNA structure. Yet, the vital contribution of Rosalind Franklin remains obscured in the background, akin to an unsung hero in a rock band, diligently executing laborious tasks while the leads hog the limelight. The failure to accord proper credit transcends mere historical oversights; it represents a broader societal lapse. It's akin to the moment you forget a friend's birthday, but on a global scale, with ramifications far weightier and fewer cake remnants.

Beyond the aversion to replicating the missteps of our historical forebears, it is high time we acknowledged the diversity inherent in the attribution of credit. It is time to peruse the closing credits and encounter a roster as diverse as a music festival lineup. Granting due credit is not solely a historical imperative but an ethical one. It involves recognizing that everyone played a role in this intricate, convoluted narrative, even those relegated to the sidelines without a single line.

In conclusion, let us refrain from emulating the individuals who chronicle history as if crafting a high school yearbook, selectively highlighting only the famous figures. Instead, let us accord credit where it rightfully belongs, glean lessons from the epic failures of the past, and forge a future that transcends the trappings of a historical blooper reel, aspiring to be an opulent masterpiece worthy of acclaim.

Notes:

History is woven with the intricate threads of triumphs and tragedies, acts of heroism and unspeakable horrors, and the occasional individual who stumbled unwittingly into greatness while pursuing mundane objectives like locating misplaced car keys. It constitutes a tumultuous journey through the annals of time, where participants either secure their names in the eternal record or, more frequently, fade into obscurity, akin to the hazy memories of regrettable choices from the previous night. Let's delve into the imperative principle of ascribing due recognition. It mirrors the ethos of history – treating others' contributions with the same respect one would desire for their own. History often resembles a tabloid column composed by a discerning neighbor privy to everyone's affairs yet prone to misrepresenting the finer details.

Consider the Civil Rights Movement, an illustration of Martin Luther King Jr. basking in the spotlight like a Broadway diva. However, behind the scenes, an ensemble cast of predominantly female unsung heroes toiled tirelessly for justice. It's reminiscent of an Oscars ceremony, where everyone anticipates their moment, but the industry consistently neglects distributing well-deserved accolades. Then there's the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, an unsettling narrative of individuals, assuming they were enrolling in a health spa, unwittingly becoming subjects of an unethical experiment. If only their involuntary sacrifice garnered the acknowledgment it warranted, perhaps they would have preferred a spa day.

Now, let's scrutinize the convoluted DNA storyline. James Watson and Francis Crick bask in the glory of the Nobel Prize for unraveling the DNA structure. Yet, the vital contribution of Rosalind Franklin remains obscured in the background, akin to an unsung hero in a rock band, diligently executing laborious tasks while the leads hog the limelight. The failure to accord proper credit transcends mere historical oversights; it represents a broader societal lapse. It's akin to the moment you forget a friend's birthday, but on a global scale, with ramifications far weightier and fewer cake remnants.

Beyond the aversion to replicating the missteps of our historical forebears, it is high time we acknowledged the diversity inherent in the attribution of credit. It is time to peruse the closing credits and encounter a roster as diverse as a music festival lineup. Granting due credit is not solely a historical imperative but an ethical one. It involves recognizing that everyone played a role in this intricate, convoluted narrative, even those relegated to the sidelines without a single line.

In conclusion, let us refrain from emulating the individuals who chronicle history as if crafting a high school yearbook, selectively highlighting only the famous figures. Instead, let us accord credit where it rightfully belongs, glean lessons from the epic failures of the past, and forge a future that transcends the trappings of a historical blooper reel, aspiring to be an opulent masterpiece worthy of acclaim.

Notes:

- Proper credit in history is crucial for presenting accurate events, acknowledging contributions, and preventing distorted historical narratives.

- Recognizing diverse contributions, such as those in the Civil Rights Movement, ensures a more inclusive view of the past beyond prominent figures.

- Failure to give proper credit can perpetuate historical inaccuracies and marginalize certain groups, as seen in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

- Rosalind Franklin's case in the discovery of DNA structure underscores the importance of crediting all contributors for a comprehensive understanding.

- Studying the subject today promotes ethical considerations, encouraging acknowledgment of the impact of individuals and groups in historical research.

- Understanding the consequences of historical misattribution shapes efforts to create a more just and inclusive future, emphasizing fairness and equity in recording and sharing history.

STATE OF THE UNION

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- COMING SOON

READING

Carnes, Chapter 21: The Age of Reform

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Carnes, Chapter 21: The Age of Reform

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... Unionization was growing. Shortly after the turn of the century there were 2 million members of labor unions (one in fourteen workers), 80 percent of them in the American Federation of Labor. The AFL was an exclusive union-almost all male, almost all white, almost all skilled workers. Although the number of women workers kept growing-it doubled from 4 million in 1890 to 8 million in 1910, and women were one-fifth of the labor force-only one in a hundred belonged to a union.

Black workers in 1910 made one-third of the earnings of white workers. Although Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL, would make speeches about its belief in equal opportunity, the Negro was excluded from most AFL unions. Gompers kept saying he did not want to interfere with the 'internal affairs' of the South; 'I regard the race problem as one with which you people of the Southland will have to deal; without the interference, too, of meddlers from the outside.'..."

"... Unionization was growing. Shortly after the turn of the century there were 2 million members of labor unions (one in fourteen workers), 80 percent of them in the American Federation of Labor. The AFL was an exclusive union-almost all male, almost all white, almost all skilled workers. Although the number of women workers kept growing-it doubled from 4 million in 1890 to 8 million in 1910, and women were one-fifth of the labor force-only one in a hundred belonged to a union.

Black workers in 1910 made one-third of the earnings of white workers. Although Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL, would make speeches about its belief in equal opportunity, the Negro was excluded from most AFL unions. Gompers kept saying he did not want to interfere with the 'internal affairs' of the South; 'I regard the race problem as one with which you people of the Southland will have to deal; without the interference, too, of meddlers from the outside.'..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... A popular 1901 magazine, Current Literature, collated available census data about American males at the turn of the century. It reported that the typical American man was British by ancestry, with traces of German; was five feet nine inches tall (or about two inches taller than average European males); and had three living children and one who had died in infancy. A Protestant, the average American male was a Republican, subscribed to a newspaper, and lived in a two-story, seven-room house. His estate was valued at about $5,000, of which $750 was in a bank account or other equities. He drank more than seven gallons of liquor a year, consumed seventy-five gallons of beer, and smoked twenty pounds of tobacco. City males earned about $750 a year, farmers about $550, and they paid only 3 percent of their income in taxes. Compared to their European counterparts, Americans were vastly better off, leading the world with a per capita income of $227 as opposed to the British male’s $181 and a Frenchman’s $161—partially because of lower taxes (British men paid 9 percent of their income, and the French, 12 percent).

Standard income for industrial workers averaged $559 per year; gas and electricity workers earned $543 per year; and even lower-skilled labor was receiving $484 a year. Of course, people in unusual or exceptional jobs could make a lot more money. Actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1906 earned $1 million for her movies, and heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson took home a purse of $5,000 when he won the Heavyweight Boxing Championship of 1908. Even more 'normal' (yet still specialized) jobs brought high earnings. The manager of a farm-implement department could command $2,000 per year in 1905 or an actuary familiar with western insurance could make up to $12,000 annually, according to ads in the New York Times.

What did that buy? An American in 1900 spent $30 a year on clothes, $82 for food, $4 for doctors and dentists, and gave $9 to religion and welfare. A statistic that might horrify modern readers, however, shows that tobacco expenditures averaged more than $6, or more than personal care and furniture put together! A quart of milk went for 6 cents, a pound of pork for nearly 17 cents, and a pound of rice for 8 cents; for entertainment, a good wrestling match in South Carolina cost 25 cents, and a New York opera ticket to Die Meistersinger cost $1.50. A working woman earned about $365 a year, and she spent $55 on clothes, $78 on food, and $208 on room and board.4 Consider the example of Mary Kennealy, an unmarried Irish American clerk in Boston, who made $7 a week (plus commissions) and shared a bedroom with one of the children in the family she boarded with. (The family of seven, headed by a loom repairman, earned just over $1,000 a year, and had a five-room house with no electricity or running water.) At work Kennealy was not permitted to sit; she put in twelve to sixteen hours a day during a holiday season. Although more than 80 percent of the clerks were women, they were managed by men, who trusted them implicitly. One executive said, 'We never had but four dishonest girls, and we’ve had to discharge over 40 boys in the same time.' 'Boys smoke and lose at cards,' the manager dourly noted."

"... A popular 1901 magazine, Current Literature, collated available census data about American males at the turn of the century. It reported that the typical American man was British by ancestry, with traces of German; was five feet nine inches tall (or about two inches taller than average European males); and had three living children and one who had died in infancy. A Protestant, the average American male was a Republican, subscribed to a newspaper, and lived in a two-story, seven-room house. His estate was valued at about $5,000, of which $750 was in a bank account or other equities. He drank more than seven gallons of liquor a year, consumed seventy-five gallons of beer, and smoked twenty pounds of tobacco. City males earned about $750 a year, farmers about $550, and they paid only 3 percent of their income in taxes. Compared to their European counterparts, Americans were vastly better off, leading the world with a per capita income of $227 as opposed to the British male’s $181 and a Frenchman’s $161—partially because of lower taxes (British men paid 9 percent of their income, and the French, 12 percent).

Standard income for industrial workers averaged $559 per year; gas and electricity workers earned $543 per year; and even lower-skilled labor was receiving $484 a year. Of course, people in unusual or exceptional jobs could make a lot more money. Actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1906 earned $1 million for her movies, and heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson took home a purse of $5,000 when he won the Heavyweight Boxing Championship of 1908. Even more 'normal' (yet still specialized) jobs brought high earnings. The manager of a farm-implement department could command $2,000 per year in 1905 or an actuary familiar with western insurance could make up to $12,000 annually, according to ads in the New York Times.

What did that buy? An American in 1900 spent $30 a year on clothes, $82 for food, $4 for doctors and dentists, and gave $9 to religion and welfare. A statistic that might horrify modern readers, however, shows that tobacco expenditures averaged more than $6, or more than personal care and furniture put together! A quart of milk went for 6 cents, a pound of pork for nearly 17 cents, and a pound of rice for 8 cents; for entertainment, a good wrestling match in South Carolina cost 25 cents, and a New York opera ticket to Die Meistersinger cost $1.50. A working woman earned about $365 a year, and she spent $55 on clothes, $78 on food, and $208 on room and board.4 Consider the example of Mary Kennealy, an unmarried Irish American clerk in Boston, who made $7 a week (plus commissions) and shared a bedroom with one of the children in the family she boarded with. (The family of seven, headed by a loom repairman, earned just over $1,000 a year, and had a five-room house with no electricity or running water.) At work Kennealy was not permitted to sit; she put in twelve to sixteen hours a day during a holiday season. Although more than 80 percent of the clerks were women, they were managed by men, who trusted them implicitly. One executive said, 'We never had but four dishonest girls, and we’ve had to discharge over 40 boys in the same time.' 'Boys smoke and lose at cards,' the manager dourly noted."

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"... Ordinary Americans who preferred leisure over work had no spokesmen. All the major American labor organizations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were as deeply committed to the work ethic as were the first Puritan settlers. In 1866 William H. Sylvis founded the National Labor Union, the first federation of trade unions in the United States, not only to protect the economic interests of its members but also to 'elevate the moral, social, and intellectual condition' of all workers. This meant, above all, instructing them that to labor was to 'carry out God's wise purposes.' The Knights of Labor replaced the National Labor Union as the major national labor organization in the 1870s and 1880s but carried forward the commitment to work over leisure. In 1879, when Terrence Powderly, a Pennsylvania machinist, took over the Knights, he opened its ranks to women, blacks, immigrants, and unskilled workers. This was a radical step in a period when most craft unions would admit none of them. But Powderly's intention was to spread a conservative message to the uninitiated. All new members of the organization were required to recite a 'Ritual of Initiation' that declared, 'In the beginning, God ordained that man should labor, not as a curse, but as a blessing.' The purpose of the organization was 'to glorify God in [labor's] exercise.' Powderly and the Knights advocated reducing the number of labor hours but only because they believed excessive work undermined the work ethic-men became machines unable to appreciate the glory of labor..."

"... Ordinary Americans who preferred leisure over work had no spokesmen. All the major American labor organizations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were as deeply committed to the work ethic as were the first Puritan settlers. In 1866 William H. Sylvis founded the National Labor Union, the first federation of trade unions in the United States, not only to protect the economic interests of its members but also to 'elevate the moral, social, and intellectual condition' of all workers. This meant, above all, instructing them that to labor was to 'carry out God's wise purposes.' The Knights of Labor replaced the National Labor Union as the major national labor organization in the 1870s and 1880s but carried forward the commitment to work over leisure. In 1879, when Terrence Powderly, a Pennsylvania machinist, took over the Knights, he opened its ranks to women, blacks, immigrants, and unskilled workers. This was a radical step in a period when most craft unions would admit none of them. But Powderly's intention was to spread a conservative message to the uninitiated. All new members of the organization were required to recite a 'Ritual of Initiation' that declared, 'In the beginning, God ordained that man should labor, not as a curse, but as a blessing.' The purpose of the organization was 'to glorify God in [labor's] exercise.' Powderly and the Knights advocated reducing the number of labor hours but only because they believed excessive work undermined the work ethic-men became machines unable to appreciate the glory of labor..."

What Does Professor Lancaster Think?Behold the captivating narrative of the labor movement, that daring chronicle of workers uniting against the malevolence of tyrannical employers and corporations. It resembles a cinematic superhero epic, albeit with fewer capes and a surplus of picket signs. Envision a diverse ensemble of factory workers, miners, and occasionally disgruntled baristas joining forces to pursue equitable wages and reasonable breaks. Behind the scenes, it unfolded more like a political intrigue akin to Game of Thrones than the harmonious collaboration of the Avengers. The American Federation of Labor possessed the not-so-superpower of exclusivity, resembling an invite-only affair at an exclusive nightclub. Apologies, women and minorities, you weren't on the guest list.

In yesteryears, unions resembled the high school cliques portrayed in '80s movies – the jocks, the nerds, and the drama geeks. The AFL constituted the cool kids' table, leaving others relegated to less favorable lunch spots. If you happened to be black, your earnings fell short of a fair-skinned counterpart, and joining a union was as improbable as encountering a unicorn in a Walmart parking lot.

Enter the Great Migration, a massive migration of black individuals from the rural South to urban areas. One might assume this presented an ideal opportunity for unions to embrace diversity, yet they adhered to exclusionary practices, stating, "Apologies, we're at capacity. Try the next union down the street." Unions, in their purported wisdom, hopped on the xenophobia train, endorsing immigration laws that sidelined Latin American and Asian immigrants, all under the guise of job protection.

And the revelations persist. Some unions, in their progressive thinking, viewed women as a watered-down version of male workers – less productive, less capable, and certainly not deserving of equal pay. One wonders why they didn't propose separate water fountains for women. Religious leaders, the moral compasses of society, also offered their insights. "Submit to your employers," they proclaimed as if insinuating that Jesus would have endorsed unpaid overtime. The labor movement exhibited more divisions than a breakup album, with Catholics and Protestants quarreling like siblings vying for the last slice of pizza.

Now, onto the Knights of Labor, the early trailblazers of the labor movement. They championed inclusivity, embracing women, blacks, immigrants, and even the eccentric stamp collector. However, their commitment to challenging the status quo proved as resilient as my dedication to a New Year's resolution. They spoke the rhetoric but sidestepped real issues like a cat avoiding a bath. Indeed, the labor movement notched some victories, persuading employers that subjecting a 10-year-old to a 16-hour workday was excessive. However, let's not romanticize it. The movement was as imperfect as a Hollywood reboot of a classic film.

Could you revisit this tumultuous history? Because, my acquaintances, comprehending our origins constitutes the initial stride toward deciphering our future. It serves as a cautionary narrative, a reminder that even the most virtuous causes can stumble. In the grand spectacle of life, we're akin to tightrope walkers without a safety net. Nevertheless, we can reflect, chuckle at the absurdity, and glean a lesson. If history imparts anything, the quest for justice and equality is a protracted journey, not a fleeting sprint. So, please fasten those sneakers and continue marching because the spectacle must be there. The spectacle must endure.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

In yesteryears, unions resembled the high school cliques portrayed in '80s movies – the jocks, the nerds, and the drama geeks. The AFL constituted the cool kids' table, leaving others relegated to less favorable lunch spots. If you happened to be black, your earnings fell short of a fair-skinned counterpart, and joining a union was as improbable as encountering a unicorn in a Walmart parking lot.

Enter the Great Migration, a massive migration of black individuals from the rural South to urban areas. One might assume this presented an ideal opportunity for unions to embrace diversity, yet they adhered to exclusionary practices, stating, "Apologies, we're at capacity. Try the next union down the street." Unions, in their purported wisdom, hopped on the xenophobia train, endorsing immigration laws that sidelined Latin American and Asian immigrants, all under the guise of job protection.

And the revelations persist. Some unions, in their progressive thinking, viewed women as a watered-down version of male workers – less productive, less capable, and certainly not deserving of equal pay. One wonders why they didn't propose separate water fountains for women. Religious leaders, the moral compasses of society, also offered their insights. "Submit to your employers," they proclaimed as if insinuating that Jesus would have endorsed unpaid overtime. The labor movement exhibited more divisions than a breakup album, with Catholics and Protestants quarreling like siblings vying for the last slice of pizza.

Now, onto the Knights of Labor, the early trailblazers of the labor movement. They championed inclusivity, embracing women, blacks, immigrants, and even the eccentric stamp collector. However, their commitment to challenging the status quo proved as resilient as my dedication to a New Year's resolution. They spoke the rhetoric but sidestepped real issues like a cat avoiding a bath. Indeed, the labor movement notched some victories, persuading employers that subjecting a 10-year-old to a 16-hour workday was excessive. However, let's not romanticize it. The movement was as imperfect as a Hollywood reboot of a classic film.

Could you revisit this tumultuous history? Because, my acquaintances, comprehending our origins constitutes the initial stride toward deciphering our future. It serves as a cautionary narrative, a reminder that even the most virtuous causes can stumble. In the grand spectacle of life, we're akin to tightrope walkers without a safety net. Nevertheless, we can reflect, chuckle at the absurdity, and glean a lesson. If history imparts anything, the quest for justice and equality is a protracted journey, not a fleeting sprint. So, please fasten those sneakers and continue marching because the spectacle must be there. The spectacle must endure.

THE RUNDOWN

- The U.S. labor movement's history is a tapestry of struggles, achievements, and setbacks.

- Early unions, like the AFL, were exclusive, primarily representing white, skilled male workers.

- Racial divisions were pronounced, with Black workers facing exclusion and earning significantly less.

- Some unions supported divisive policies, such as restrictive immigration laws and gender-based employment restrictions.

- The Knights of Labor initially embraced inclusivity but struggled to challenge existing power structures.

- Understanding historical exclusions helps address current workplace inequalities and fosters inclusivity in the modern labor movement.

QUESTIONS

- What were some exclusionary practices endorsed by unions, and how did they affect Latin American, Asian, and black individuals?

- In what ways did some unions perpetuate gender stereotypes and discriminatory views towards women, as mentioned in the passage?

- What insights did religious leaders provide during the labor movement, and how did their statements contribute to the divisions within the movement?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

WATCH

The Century: America's Time - The Beginning: Seeds of Change (1999)

WATCH

The Century: America's Time - The Beginning: Seeds of Change (1999)

THE RUNDOWN

Step into the tumultuous saga of 20th-century America, where the echoes of history are captured in analog recordings, composing a soundtrack that mirrors the rollercoaster of unfolding events. From the unexpected shockwaves of Pearl Harbor to the discordant tones of Kennedy's assassination, this century unfolds like a cosmic jest, with tragedy as its poignant punchline. Across the societal spectrum, from shifts in education to the dynamics of race and the intricate dance with advancing technology, a tableau emerges where structures stand as stoic witnesses to transformative shifts, nostalgically whispering about times gone by. Immigrants pursuing the elusive American Dream find themselves in a crucible of hope and disenchantment. In a documentary eloquently narrated by the seasoned Peter Jennings, sweatshops give birth to fashion; reform movements clash with persistent inequality, and technological strides carve the path for an era that blends awe and absurdity. Welcome to the 20th century, where the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire is a mere misstep in fashion, leading up to a grand finale that sets the stage for the turbulent sequel—World War I. It's an unpredictable journey, and the historical gramophone continues its unending spin.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY KERMS

KEY KERMS

- Teller Amendment

- Open Door Policy

- Ragtime

- 1900s Fashion

- Casey Jones

- Washington, Carver & Du Bois

- Galveston Hurricane

- Puerto Rico

- Wrestling

- Breakup of Northern Securities

- Little Nemo

- First radio program

- Brownsville raid

- Upton Sinclair

- "Gentlemen's Agreement"

- 1907 Eugenic Sterilization Law for People with Disabilities

- 1910s Fashion

- Jazz Music

- White-Slave Traffic Act

- Triangle Shirtwaist factory

- Paul Dudley White

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity #1: Gallery Walk

Activity #1: Gallery Walk

Activity #2: Exploring the Progressive Era

- Objective: Your goal is to collaboratively research and present a specific aspect of the Progressive Era to deepen your understanding of the key events, social movements, and political changes in the United States from 1899 to 1914.

Instructions:- Group Formation: Form small groups of 3-5 students.

- Each group will be assigned a unique aspect of the Progressive Era to research and present. Your options include topics like Women's Suffrage Movement, Labor Movement and Strikes, Political Reforms, Progressive Presidents, or Social and Environmental Reforms.

- Dive into your assigned topic using a mix of primary and secondary sources. Explore causes, key figures, events, and the impact of your chosen aspect on the Progressive Era.

- Prepare a 15-minute presentation covering:

- Brief overview of your topic.

- Historical context, including events leading to the Progressive Era.

- Significant events or milestones during the Progressive Era.

- Impact of your topic on society and subsequent historical developments.

- Use visual aids (slides, images, documents) to enhance understanding.

- Each group will present their findings to the class.

- After each presentation, be ready to answer questions from your classmates. This is an opportunity for everyone to engage in discussions and gain a comprehensive understanding of the Progressive Era.

- Evaluate your classmates' presentations using a provided form. Consider aspects like content accuracy, clarity, engagement, and effective use of visuals.

- Wrap up the activity with a class discussion. Reflect on common themes, connections between different topics, and the overall significance of the Progressive Era

- Remember, this activity is designed to enhance your research, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication skills. Have fun exploring the Progressive Era together!

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

The early 20th century witnessed significant developments in industrialization, urbanization, and the emergence of a wealth chasm vast enough to accommodate a procession of Gatsby's automobiles. Envision the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911—a place that renders Dante's Inferno a reprieve in comparison. Working conditions were deplorable, suggesting a deliberate pursuit of the record for "Most Violations of Human Rights in a Single Shift." However, out of this tragedy, a call for reform sprang forth, as if to acknowledge the inadvertent ignition of workers merited corrective action.

Enter the Progressive Movement, akin to historical champions draped in metaphorical capes woven from labor safeguards, food safety mandates, and child labor statutes. Their heroic feats, reminiscent of the Avengers, involved battling not intergalactic threats but advocating for a 40-hour workweek and safer sustenance. And, of course, the suffrage movement, championing gender equality by granting women the right to vote—an acknowledgment that women possessed intellectual prowess, a revelation that might have seemed astonishing to some.

Amidst this cacophony, the Harlem Renaissance burgeoned, where black leaders and intellectuals made strides despite confronting discrimination rivaling that faced by a black cat on Friday the 13th. Do you know if the lesson is here? Even in a world that relegated them to second-class citizenship, these individuals forged art, music, and literature reverberating through time's corridors. Take that, Jim Crow. Skipping ahead to post-World War I, the U.S. asserted its global influence. Woodrow Wilson aspired to be a hero through the League of Nations, yet the Senate demurred. A classic collision between idealism and the pragmatic realities of politics—a reminder that idealism, much like herding cats, is conceptually appealing but fraught with challenges.

Consider the Tuskegee Syphilis Study—an ethically dubious experiment that raises questions about the moral compass of its architects. Neglecting due credit and ethical considerations in historical research is akin to constructing a house of cards in a wind tunnel—a precarious endeavor destined to collapse unsightly. Lastly, the U.S. labor movement emerges as unsung workplace heroes, advocating for fair wages and reasonable hours. However, their exclusivity mirrored a downtown nightclub, admitting only the elite and leaving others cold. A valuable lesson surfaces: If championing workers' rights, ensure it's a celebration open to all.

In the early 20th century, intricate tapestry, tragedy, triumph, and occasional absurdity were woven together. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the suffrage movement, and geopolitical power play form chapters in an unputdownable historical narrative. Let's draw inspiration from history, accord due credit, and heed the lessons of our forebears' errors. Failing to do so condemns us to a repetitive cycle. And who among us desires a revisit of syphilis studies or exclusive labor unions? Certainly not us. Here's to a future where history is an inclusive celebration accessible to all.

Or, in other words:

The early 20th century witnessed significant developments in industrialization, urbanization, and the emergence of a wealth chasm vast enough to accommodate a procession of Gatsby's automobiles. Envision the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911—a place that renders Dante's Inferno a reprieve in comparison. Working conditions were deplorable, suggesting a deliberate pursuit of the record for "Most Violations of Human Rights in a Single Shift." However, out of this tragedy, a call for reform sprang forth, as if to acknowledge the inadvertent ignition of workers merited corrective action.

Enter the Progressive Movement, akin to historical champions draped in metaphorical capes woven from labor safeguards, food safety mandates, and child labor statutes. Their heroic feats, reminiscent of the Avengers, involved battling not intergalactic threats but advocating for a 40-hour workweek and safer sustenance. And, of course, the suffrage movement, championing gender equality by granting women the right to vote—an acknowledgment that women possessed intellectual prowess, a revelation that might have seemed astonishing to some.

Amidst this cacophony, the Harlem Renaissance burgeoned, where black leaders and intellectuals made strides despite confronting discrimination rivaling that faced by a black cat on Friday the 13th. Do you know if the lesson is here? Even in a world that relegated them to second-class citizenship, these individuals forged art, music, and literature reverberating through time's corridors. Take that, Jim Crow. Skipping ahead to post-World War I, the U.S. asserted its global influence. Woodrow Wilson aspired to be a hero through the League of Nations, yet the Senate demurred. A classic collision between idealism and the pragmatic realities of politics—a reminder that idealism, much like herding cats, is conceptually appealing but fraught with challenges.

Consider the Tuskegee Syphilis Study—an ethically dubious experiment that raises questions about the moral compass of its architects. Neglecting due credit and ethical considerations in historical research is akin to constructing a house of cards in a wind tunnel—a precarious endeavor destined to collapse unsightly. Lastly, the U.S. labor movement emerges as unsung workplace heroes, advocating for fair wages and reasonable hours. However, their exclusivity mirrored a downtown nightclub, admitting only the elite and leaving others cold. A valuable lesson surfaces: If championing workers' rights, ensure it's a celebration open to all.

In the early 20th century, intricate tapestry, tragedy, triumph, and occasional absurdity were woven together. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the suffrage movement, and geopolitical power play form chapters in an unputdownable historical narrative. Let's draw inspiration from history, accord due credit, and heed the lessons of our forebears' errors. Failing to do so condemns us to a repetitive cycle. And who among us desires a revisit of syphilis studies or exclusive labor unions? Certainly not us. Here's to a future where history is an inclusive celebration accessible to all.

Or, in other words:

- Early 20th-century U.S.: Unprecedented growth, reshaping the nation. Prosperity, technology, urbanization, but challenges emerge: deplorable working conditions, urban issues, wealth gap.

- Response to challenges: Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire catalyzes reforms. Public awareness drives labor and workplace safety changes.

- Progressive Movement leads to reforms: labor protections, food safety, child labor laws. Culminates in the 19th Amendment securing women's right to vote.

- Despite discrimination, civil rights momentum fosters cultural movements. Harlem Renaissance showcases significant Black contributions.

- U.S. emerges as a global power after World War I. Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations faces challenges, revealing tensions between visions and realities.

- Consequences of historical oversights, like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Understanding labor movement exclusions is vital for addressing present workplace inequalities.

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #4

Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle, a novel published in 1906, to highlight the difficult and oppressed lives of immigrants in industrialized cities in the United States, such as Chicago. The book focused on the meat industry and its poor working conditions as a way to promote socialism in the country. However, readers were more shocked by the depiction of health violations and unsanitary practices in the meat packing industry, which sparked public outrage and led to significant reforms, including the Meat Inspection Act. Sinclair later remarked that he had intended to appeal to readers' emotions, but ended up affecting them through their stomachs instead.

Watch this short clip (or read the Jungle in its entirety; whatever floats your boat!) and answer the following:

- Forum Discussion #4

Forum Discussion #4

Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle, a novel published in 1906, to highlight the difficult and oppressed lives of immigrants in industrialized cities in the United States, such as Chicago. The book focused on the meat industry and its poor working conditions as a way to promote socialism in the country. However, readers were more shocked by the depiction of health violations and unsanitary practices in the meat packing industry, which sparked public outrage and led to significant reforms, including the Meat Inspection Act. Sinclair later remarked that he had intended to appeal to readers' emotions, but ended up affecting them through their stomachs instead.

Watch this short clip (or read the Jungle in its entirety; whatever floats your boat!) and answer the following:

What role does the concept of the free market play in Upton Sinclair's The Jungle and how does the novel critique or challenge this idea?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

In the era of industrial upheaval, the shift from agrarian tools to mechanized assembly lines and the exchange of fresh air for the pungent scent of labor exploitation marked a period of societal advancement. Envisioned as a utopian future fueled by steam-powered innovations, it instead unfolded as a dystopian realm resembling a capitalist-designed amusement park. The promise of an improved urban life mirrored the hollow apologies of politicians. Upton Sinclair, an investigative journalism maestro, pulled back the curtain on the obscured reality of the distorted industrial landscape with "The Jungle," offering a stark portrayal of human suffering amidst Chicago's nightmarish meatpacking industry. Sinclair immersed himself among the authentic protagonists—the underpaid, overburdened laborers caught in the gears of progress—eschewing refined literary gatherings for gritty reality. Jurgis Rudkus, the reluctant protagonist, wasn't a caped hero but a cog lubricated by the toil of the working class. Going beyond mere narration, Sinclair forcefully presented the horrors of the meatpacking sector. The resultant Meat Inspection Act alleviated concerns about surprise elements in sausages. Still, genuine change emerged from laborers declaring "No more" and administering medicine to the affluent elite. Sinclair's aspiration to be the voice for the muted was a prologue; the actual headline act was the growing discontent among the working class—a collective defiance against reigning powers. So, when you savor a hamburger, thank Upton Sinclair for sparing you dubious meat and salute the unsung heroes—the laborers who opted out of being processed as lunch. "The Jungle" wasn't just a literary work; it embodied a resounding battle cry.

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

In the era of industrial upheaval, the shift from agrarian tools to mechanized assembly lines and the exchange of fresh air for the pungent scent of labor exploitation marked a period of societal advancement. Envisioned as a utopian future fueled by steam-powered innovations, it instead unfolded as a dystopian realm resembling a capitalist-designed amusement park. The promise of an improved urban life mirrored the hollow apologies of politicians. Upton Sinclair, an investigative journalism maestro, pulled back the curtain on the obscured reality of the distorted industrial landscape with "The Jungle," offering a stark portrayal of human suffering amidst Chicago's nightmarish meatpacking industry. Sinclair immersed himself among the authentic protagonists—the underpaid, overburdened laborers caught in the gears of progress—eschewing refined literary gatherings for gritty reality. Jurgis Rudkus, the reluctant protagonist, wasn't a caped hero but a cog lubricated by the toil of the working class. Going beyond mere narration, Sinclair forcefully presented the horrors of the meatpacking sector. The resultant Meat Inspection Act alleviated concerns about surprise elements in sausages. Still, genuine change emerged from laborers declaring "No more" and administering medicine to the affluent elite. Sinclair's aspiration to be the voice for the muted was a prologue; the actual headline act was the growing discontent among the working class—a collective defiance against reigning powers. So, when you savor a hamburger, thank Upton Sinclair for sparing you dubious meat and salute the unsung heroes—the laborers who opted out of being processed as lunch. "The Jungle" wasn't just a literary work; it embodied a resounding battle cry.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.