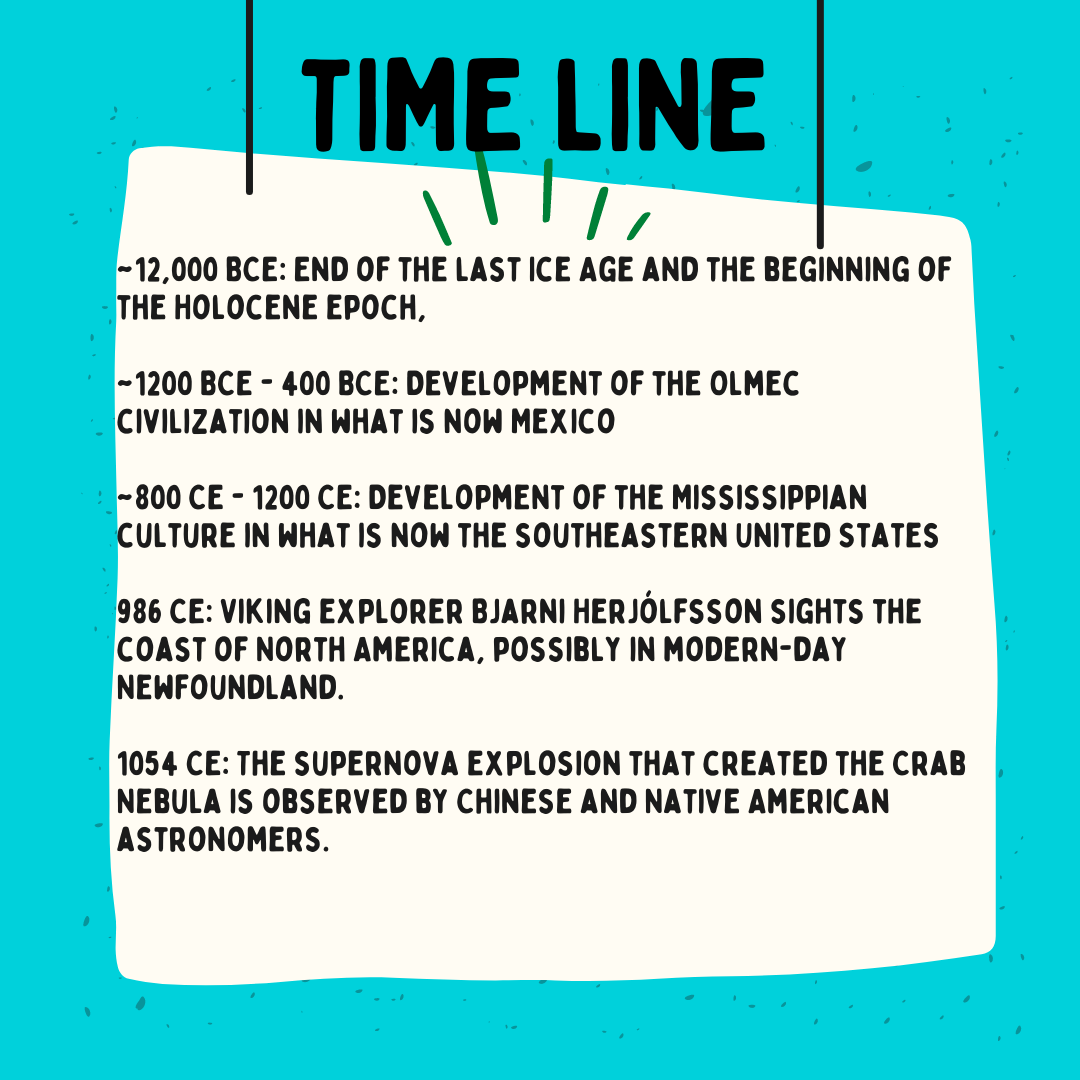

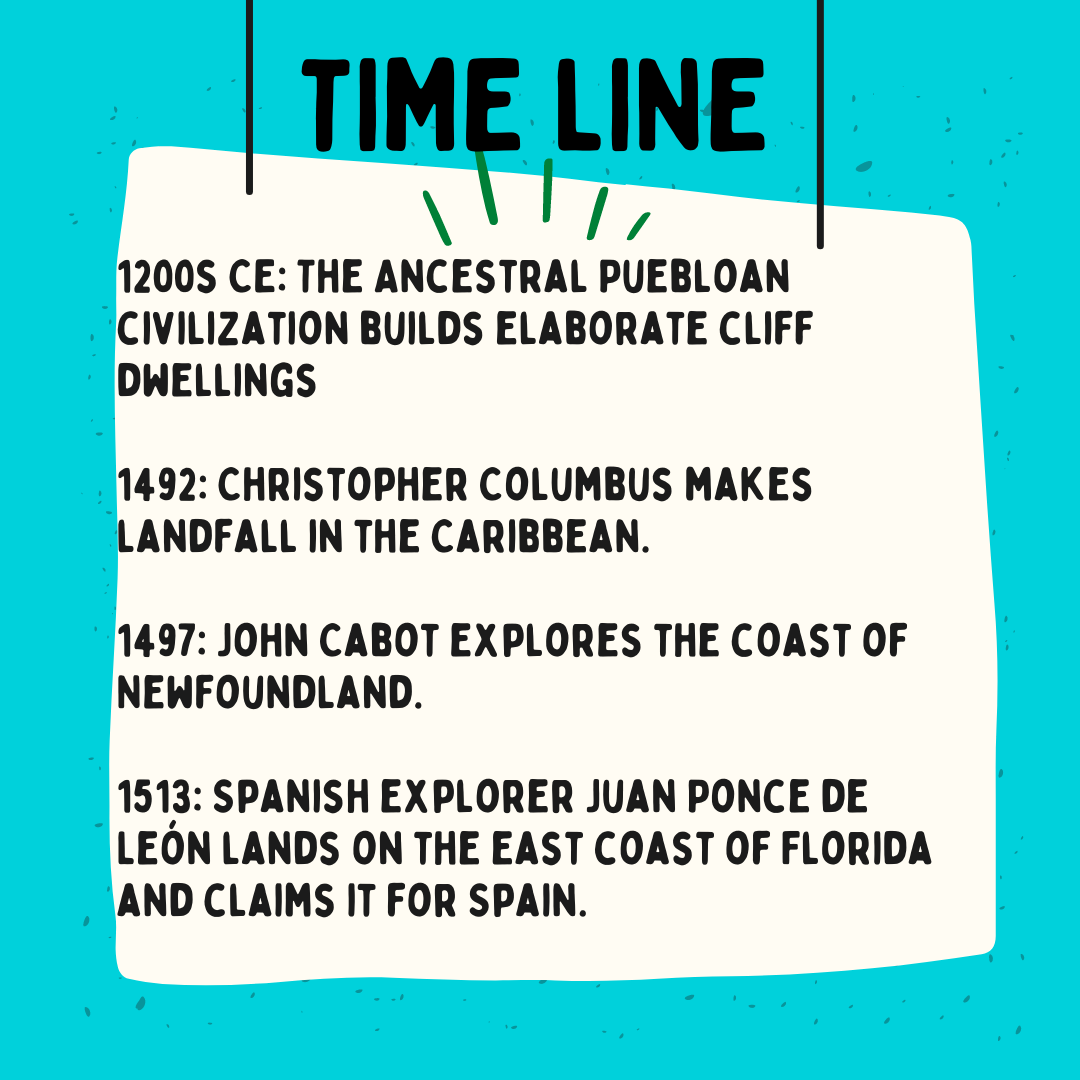

Module One: In the Beginning (4,600 Million BCE-1513 CE

Once upon a time, long before anyone could even fathom selfies or fast food, the Earth was brewing up its grand design. Over billions of years, the molten core bubbled and toiled, giving rise to continents and landmasses that would eventually host the United States. It's a geological saga that rivals any epic tale of conquest and intrigue.

In a remarkably swift geological timescale, roughly 15,000 years ago, an incredible transformation occurred as Native Americans emerged and indelibly influenced the world. With an unparalleled understanding of their surroundings, they chose their habitation wisely, showing a remarkable grasp of the landscape. This profound bond with the natural world permeated every aspect of their existence, shaping their language, culture, spirituality, and governance in ways that left an enduring impact on history. Their legacy is genuinely awe-inspiring.

But then, as luck would have it, European explorers entered the stage, all swagger and ambition. Led by Christopher Columbus, they sailed forth to claim their stake in the New World. And stake claims they did, establishing colonies that would later become the good old U.S.

Yet, like many grand tales of conquest, this one wasn't all sunshine and rainbows. The arrival of the Europeans spelled disaster for the Native American populations. Forced from their ancestral lands, plagued by disease and violence, their world turned upside down. It's a grim reminder that history's heroes and villains often intertwine.

But hold on tight because this story has its moments of brilliance too. The Declaration of Independence in 1776 marked a turning point, a daring declaration of freedom, equality, and a newfound pursuit of happiness. It was the blueprint for a nation, with the Constitution laying down the ground rules for limited government and individual rights.

And the nation's economic boom? Well, that was thanks to Mother Nature's generous gifts. From fertile farmlands to riches buried deep in the Earth, the United States struck it big. Industrialization and prosperity became the name of the game.

Alas, there's no escaping the shadows cast by the past. The enduring impact of colonization casts long shadows, leaving behind a haunting inheritance of suffering and disparity for both Native Americans and African Americans. The environmental consequences are equally distressing as exploitation exacts its toll, and its reckoning remains pending.

Yet, confronting these harsh realities, however unsettling, is imperative. We can forge a path toward a more promising future only by acknowledging our history. Drawing wisdom from the trials and victories of the past, embracing the richness of diversity, and tirelessly advocating for equality shall unlock the door to a brighter and more hopeful tomorrow.

So, let this tapestry of history serve as a guidepost. A reminder of the United States' journey from a geological marvel to a land of dreams and opportunities. As we embark on our journey forward, let us draw wisdom from our history, rectify our errors, and forge a harmonious alliance in the noble quest for justice, parity, and safeguarding our delicate abode. Together, hand in hand, we shall inscribe the forthcoming narrative infused with astuteness, sagacity, and empathy that emanates from the depths of our souls.

THE RUNDOWN

- 4.6 billion years ago, the Earth was formed, laying the groundwork for the development of life and human civilization.

- The geological history of the US includes ancient oceans, mountains, and volcanoes that shaped the country's landscape and natural resources.

- Native Americans arrived approximately 15,000 years ago, influencing the country's culture and traditions.

- Europeans arrived in the 16th century, leading to the displacement of Native American populations and the establishment of colonies that became the US.

- The US became a beacon of democracy, individual rights, and limited government, with vast natural resources contributing to economic success.

- However, the negative impacts of colonization include the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans, enslavement of Africans, and exploitation of natural resources, which still have lasting impacts today.

- Studying this timeline is crucial for understanding the forces that shaped the US and addressing current issues like social inequality and environmental degradation.

QUESTIONS

- Why is it important to study events that happened millions of years ago in order to understand the United States today?

- How have the cultures and traditions of Native Americans influenced the development of the United States?

- How have the negative impacts of colonization, such as the displacement of Native Americans and the exploitation of natural resources, continued to affect the United States today?

#1 Historians are Detective

In the intoxicating world of history, historians don the trench coat and fedora, becoming savvy detectives on a mission to unravel the enigmatic tales of our past. It's like being transported to a mysterious labyrinth, where they navigate through hidden truths and buried secrets to illuminate the triumphs and tragedies of human existence.

One of these history sleuths was Tom Reilly. He tackled the ambitious task of rehabilitating the controversial figure of Oliver Cromwell in Irish history. For a jaw-dropping three decades, he dedicated himself to cracking the code of historical records, driven by a burning desire to give Cromwell's reputation a makeover. Armed with primary sources and an insatiable thirst for the truth, Reilly dared to challenge the accepted narrative that painted Cromwell's troops as ruthless killers. Instead, he took a brave stand, insisting that the killings were confined to enemy combatants who'd thrown in the towel. Talk about being fearless in the face of historical hostility!

The meticulous work of historians like Reilly reveals that they aren't just archival keepers of the past but the guardians of truth. Through their relentless pursuit of accuracy, they unearth obscure stories and bring to light the complexities of our shared heritage. With their trusty magnifying glass, they meticulously evaluate sources, separating fact from fiction and leaving no historical stone unturned.

Think of the lessons we can learn from history's grand stage! It's like a dramatic performance from the past, and historians hold the script. They empower us to make informed choices for the present and future, as they remind us that the foundations of today rest on the triumphs and tribulations of yesteryears.

But this historical detective work is a collaborative endeavor. It's a delightful dance between historians and journalists, each bringing their unique skills. Just think of the notorious Watergate scandal; it's a classic tale of collaboration between historians and journalists, a thrilling performance that uncovered the dark secrets of political intrigue. Scholars of the past bring their specialized knowledge in deciphering historical events, whereas investigative journalists utilize their adeptness in finding hidden truths through the persistent pursuit of undisclosed informants and classified records.

Ultimately, these historians do not merely disentangle the enigmas of history; they intricately interlace the tapestry of our comprehension of the world. Their meticulous detective work gives us the tools to navigate the present and shape a brighter tomorrow. So let's raise a glass to the history sleuths, the custodians of truth, and the keepers of our shared heritage.

RUNDOWN

STATE OF THE UNION

One of these history sleuths was Tom Reilly. He tackled the ambitious task of rehabilitating the controversial figure of Oliver Cromwell in Irish history. For a jaw-dropping three decades, he dedicated himself to cracking the code of historical records, driven by a burning desire to give Cromwell's reputation a makeover. Armed with primary sources and an insatiable thirst for the truth, Reilly dared to challenge the accepted narrative that painted Cromwell's troops as ruthless killers. Instead, he took a brave stand, insisting that the killings were confined to enemy combatants who'd thrown in the towel. Talk about being fearless in the face of historical hostility!

The meticulous work of historians like Reilly reveals that they aren't just archival keepers of the past but the guardians of truth. Through their relentless pursuit of accuracy, they unearth obscure stories and bring to light the complexities of our shared heritage. With their trusty magnifying glass, they meticulously evaluate sources, separating fact from fiction and leaving no historical stone unturned.

Think of the lessons we can learn from history's grand stage! It's like a dramatic performance from the past, and historians hold the script. They empower us to make informed choices for the present and future, as they remind us that the foundations of today rest on the triumphs and tribulations of yesteryears.

But this historical detective work is a collaborative endeavor. It's a delightful dance between historians and journalists, each bringing their unique skills. Just think of the notorious Watergate scandal; it's a classic tale of collaboration between historians and journalists, a thrilling performance that uncovered the dark secrets of political intrigue. Scholars of the past bring their specialized knowledge in deciphering historical events, whereas investigative journalists utilize their adeptness in finding hidden truths through the persistent pursuit of undisclosed informants and classified records.

Ultimately, these historians do not merely disentangle the enigmas of history; they intricately interlace the tapestry of our comprehension of the world. Their meticulous detective work gives us the tools to navigate the present and shape a brighter tomorrow. So let's raise a glass to the history sleuths, the custodians of truth, and the keepers of our shared heritage.

RUNDOWN

- Historians are like detectives; they use clues to understand past events and interpret findings to determine what happened.

- Irish historian Tom Reilly spent 30 years trying to rehabilitate Oliver Cromwell, a controversial figure in Irish history, by reviewing primary sources and establishing his "authentic voice."

- Reilly claims that Irish history books wrongly suggest that Cromwell's troops killed civilians while they only killed enemy combatants who had yielded.

- Historians are essential because they excavate hidden stories and understand the complexities of human experience, helping us to shape the future by learning from the past.

- Historians and detectives gather evidence to build a case, and historians must evaluate sources to ensure they are credible and relevant.

- Historians and journalists worked together to uncover the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, using confidential sources, government documents, and witness testimony to piece together a twisted tale of political intrigue.

STATE OF THE UNION

As we delve into the Earth's past, let's imagine it as a lively toddler in the cosmic playground 550 million years ago, during the Ediacaran period. This was a time devoid of modern distractions, brimming with geological and biological potential. Landmasses, like scattered Tetris pieces, adorned an ocean-soaked globe, hinting at the future supercontinent Pangaea. The oceans, more than just tepid bathwater, flirted with continental margins, nurturing avant-garde marine life under a warm, ice-free climate. Oxygen levels, at 10-15%, were on the brink of heralding the rise of complex life forms while the marine world buzzed with soft-bodied sponges, cnidarians, and surreal creatures like Dickinsonia. Microbial mats and stromatolites, crafted by cyanobacteria, stood as bio-geological skyscrapers in shallow seas. Beneath the surface, the Earth's tectonic plates engaged in a slow dance of collisions and separations, shaping landmasses and marine basins, with volcanism setting the stage for future biological richness. This period, a precursor to the Cambrian Explosion, laid the meticulous groundwork for life's grand diversification, a serene yet dynamic dawn before the cosmic fireworks of evolutionary history.

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

The Reading section—a realm where our aspirations of enlightenment often clash with the harsh realities of procrastination and the desperate reliance on Google. We soldier on through dense texts, promised 'broadening perspectives' but often wrestling with existential dread and academic pressure. With a healthy dose of sarcasm and a strong cup of coffee, I'll be your guide on this wild journey from dusty tomes to the murky depths of postmodernism. In the midst of all the pretentious prose, there's a glimmer of insight: we're all in this together, united in our struggle to survive without losing our sanity.

READING

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

RUNDOWN

READING

- Carnes Chapter One: "Beginnings"

- “For Native Americans, Sex Didn’t Come with Guilt” by John Steckley

- “Hallucinogenic Drugs in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican Cultures” by F.J.Carod-Arta

- "War in the time of Neanderthals: How our species battled for supremacy for over 100,000 years

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

RUNDOWN

- Before Europeans arrived, North America was home to many different and advanced Native American cultures, like the Mississippian mound builders and Ancestral Puebloans.

- Europeans, led by explorers like Christopher Columbus, started coming to the Americas in search of new trade routes and wealth.

- When Europeans met Native Americans, it led to significant changes for both groups. They traded goods but also exchanged diseases that significantly affected native populations.

- Spain, France, and England began to set up colonies in the Americas. They faced many challenges as they tried to establish their new settlements.

- European colonization brought significant changes to the continent, affecting the demographics and cultures of Europeans and Native Americans.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the island's beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. He later wrote of this in his log:

'They ... brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks' bells. They willingly traded everything they owned... . They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features.... They do not bear

arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane... . They would make fine servants.... With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.'

...To emphasize the heroism of Columbus and his successors as navigators and discoverers, and to de-emphasize their genocide, is not a technical necessity but an ideological choice. It serves-unwittingly-to justify what was done.

My point is not that we must, in telling history, accuse, judge, condemn Columbus in absentia. It is too late for that; it would be a useless scholarly exercise in morality. But the easy acceptance of atrocities as a deplorable but necessary price to pay for progress (Hiroshima and Vietnam, to save Western civilization; Kronstadt and Hungary, to save socialism; nuclear proliferation, to save us all)-that is still with us. One reason these atrocities are still with us is that we have learned to bury them in a mass of other facts, as radioactive wastes are buried in containers in the earth. We have learned to give them exactly the same proportion of attention that teachers and writers often give them in the most respectable of classrooms and textbooks. This learned sense of moral proportion, coming from the apparent objectivity of the scholar, is accepted more easily than when it comes from politicians at press conferences. It is therefore more deadly."

"... Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the island's beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. He later wrote of this in his log:

'They ... brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks' bells. They willingly traded everything they owned... . They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features.... They do not bear

arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane... . They would make fine servants.... With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.'

...To emphasize the heroism of Columbus and his successors as navigators and discoverers, and to de-emphasize their genocide, is not a technical necessity but an ideological choice. It serves-unwittingly-to justify what was done.

My point is not that we must, in telling history, accuse, judge, condemn Columbus in absentia. It is too late for that; it would be a useless scholarly exercise in morality. But the easy acceptance of atrocities as a deplorable but necessary price to pay for progress (Hiroshima and Vietnam, to save Western civilization; Kronstadt and Hungary, to save socialism; nuclear proliferation, to save us all)-that is still with us. One reason these atrocities are still with us is that we have learned to bury them in a mass of other facts, as radioactive wastes are buried in containers in the earth. We have learned to give them exactly the same proportion of attention that teachers and writers often give them in the most respectable of classrooms and textbooks. This learned sense of moral proportion, coming from the apparent objectivity of the scholar, is accepted more easily than when it comes from politicians at press conferences. It is therefore more deadly."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"Did Columbus Kill Most of the Indians?

The five-hundred-year anniversary of Columbus’s discovery was marked by unusual and strident controversy. Rising up to challenge the intrepid voyager’s courage and vision—as well as the establishment of European civilization in the New World—was a crescendo of damnation, which posited that the Genoese navigator was a mass murderer akin to Adolf Hitler. Even the establishment of European outposts was, according to the revisionist critique, a regrettable development. Although this division of interpretations no doubt confused and dampened many a Columbian festival in 1992, it also elicited a most intriguing historical debate: did the esteemed Admiral of the Ocean Sea kill almost all the Indians? A number of recent scholarly studies have dispelled or at least substantially modified many of the numbers generated by the anti-Columbus groups, although other new research has actually increased them. Why the sharp inconsistencies? One recent scholar, examining the major assessments of numbers, points to at least nine different measurement methods, including the time-worn favorite, guesstimates.

1. Pre-Columbian native population numbers are much smaller than critics have maintained. For example, one author claims 'Approximately 56 million people died as a result of European exploration in the New World.' For that to have occurred, however, one must start with early estimates for the population of the Western Hemisphere at nearly 100 million. Recent research suggests that that number is vastly inflated, and that the most reliable figure is nearer 53 million, and even that estimate falls with each new publication. Since 1976 alone, experts have lowered their estimates by 4 million. Some scholars have even seen those figures as wildly inflated, and several studies put the native population of North America alone within a range of 8.5 million (the highest) to a low estimate of 1.8 million. If the latter number is true, it means that the 'holocaust' or 'depopulation' that occurred was one fiftieth of the original estimates, or 800,000 Indians who died from disease and firearms. Although that number is a universe away from the estimates of 50 to 60 million deaths that some researchers have trumpeted, it still represented a destruction of half the native population. Even then, the guesstimates involve such things as accounting for the effects of epidemics—which other researchers, using the same data, dispute ever occurred—or expanding

the sample area to all of North and Central America. However, estimating the number of people alive in a region five hundred years ago has proven difficult, and recently several researchers have called into question most early estimates. For example, one method many scholars have used to arrive at population numbers—extrapolating from early explorers’ estimates of populations they could count—has been challenged by archaeological studies of the Amazon basin, where dense settlements were once thought to exist. Work in the area by Betty Meggers concludes that the early explorers’ estimates were exaggerated and that no evidence of large populations in that region

exists. N. D. Cook’s demographic research on the Inca in Peru showed that the population could have been as high as 15 million or as low as 4 million, suggesting that the measurement mechanisms have a 'plus or minus reliability factor' of 400 percent! Such 'minor' exaggerations as the tendencies of some explorers to overestimate their opponents’ numbers, which, when factored throughout numerous villages, then into entire populations, had led to overestimates of millions.

2. Native populations had epidemics long before Europeans arrived. A recent study of more than 12,500 skeletons from sixty-five sites found that native health was on a 'downward trajectory long before Columbus arrived.' Some suggest that Indians may have had a nonvenereal form of syphilis, and almost all agree that a variety of infections were widespread. Tuberculosis existed in Central and North America long before the Spanish appeared, as did herpes, polio, tick-borne fevers, giardiasis, and amebic dysentery. One admittedly controversial study by Henry Dobyns in Current Anthropology in 1966 later fleshed out over the years into his book, argued that extensive epidemics swept North America before Europeans arrived. As one authority summed up the research, 'Though the Old World was to contribute to its diseases, the New World certainly was not the Garden of Eden some have depicted.' As one might expect, others challenged Dobyns and the 'early epidemic' school, but the point remains that experts are divided. Many now discount the notion that huge epidemics swept through Central and North America; smallpox, in particular, did not seem to spread as a pandemic.

3. There is little evidence available for estimating the numbers of people lost in warfare prior to the Europeans because in general natives did not keep written records. Later, when whites could document oral histories during the Indian wars on the western frontier, they found that different tribes exaggerated their accounts of battles in totally different ways, depending on tribal custom. Some, who preferred to emphasize bravery over brains, inflated casualty numbers. Others, viewing large body counts as a sign of weakness, deemphasized their losses. What is certain is that vast numbers of natives were killed by other natives, and that only technological backwardness—the absence of guns, for example—prevented the numbers of natives killed by other natives from growing even higher.

4. Large areas of Mexico and the Southwest were depopulated more than a hundred years before the arrival of Columbus. According to a recent source, 'The majority of Southwesternists…believe that many areas of the Greater Southwest were abandoned or largely depopulated over a century before Columbus’s fateful discovery, as a result of climatic shifts, warfare, resource mismanagement, and other causes.' Indeed, a new generation of scholars puts more credence in early Spanish explorers’ observations of widespread ruins and decaying “great houses” that they contended had been abandoned for years.

5. European scholars have long appreciated the dynamic of small-state diplomacy, such as was involved in the Italian or German small states in the nineteenth century. What has been missing from the discussions about native populations has been a recognition that in many ways the tribes resembled the small states in Europe: they concerned themselves more with traditional enemies (other tribes) than with new ones (whites)."

"Did Columbus Kill Most of the Indians?

The five-hundred-year anniversary of Columbus’s discovery was marked by unusual and strident controversy. Rising up to challenge the intrepid voyager’s courage and vision—as well as the establishment of European civilization in the New World—was a crescendo of damnation, which posited that the Genoese navigator was a mass murderer akin to Adolf Hitler. Even the establishment of European outposts was, according to the revisionist critique, a regrettable development. Although this division of interpretations no doubt confused and dampened many a Columbian festival in 1992, it also elicited a most intriguing historical debate: did the esteemed Admiral of the Ocean Sea kill almost all the Indians? A number of recent scholarly studies have dispelled or at least substantially modified many of the numbers generated by the anti-Columbus groups, although other new research has actually increased them. Why the sharp inconsistencies? One recent scholar, examining the major assessments of numbers, points to at least nine different measurement methods, including the time-worn favorite, guesstimates.

1. Pre-Columbian native population numbers are much smaller than critics have maintained. For example, one author claims 'Approximately 56 million people died as a result of European exploration in the New World.' For that to have occurred, however, one must start with early estimates for the population of the Western Hemisphere at nearly 100 million. Recent research suggests that that number is vastly inflated, and that the most reliable figure is nearer 53 million, and even that estimate falls with each new publication. Since 1976 alone, experts have lowered their estimates by 4 million. Some scholars have even seen those figures as wildly inflated, and several studies put the native population of North America alone within a range of 8.5 million (the highest) to a low estimate of 1.8 million. If the latter number is true, it means that the 'holocaust' or 'depopulation' that occurred was one fiftieth of the original estimates, or 800,000 Indians who died from disease and firearms. Although that number is a universe away from the estimates of 50 to 60 million deaths that some researchers have trumpeted, it still represented a destruction of half the native population. Even then, the guesstimates involve such things as accounting for the effects of epidemics—which other researchers, using the same data, dispute ever occurred—or expanding

the sample area to all of North and Central America. However, estimating the number of people alive in a region five hundred years ago has proven difficult, and recently several researchers have called into question most early estimates. For example, one method many scholars have used to arrive at population numbers—extrapolating from early explorers’ estimates of populations they could count—has been challenged by archaeological studies of the Amazon basin, where dense settlements were once thought to exist. Work in the area by Betty Meggers concludes that the early explorers’ estimates were exaggerated and that no evidence of large populations in that region

exists. N. D. Cook’s demographic research on the Inca in Peru showed that the population could have been as high as 15 million or as low as 4 million, suggesting that the measurement mechanisms have a 'plus or minus reliability factor' of 400 percent! Such 'minor' exaggerations as the tendencies of some explorers to overestimate their opponents’ numbers, which, when factored throughout numerous villages, then into entire populations, had led to overestimates of millions.

2. Native populations had epidemics long before Europeans arrived. A recent study of more than 12,500 skeletons from sixty-five sites found that native health was on a 'downward trajectory long before Columbus arrived.' Some suggest that Indians may have had a nonvenereal form of syphilis, and almost all agree that a variety of infections were widespread. Tuberculosis existed in Central and North America long before the Spanish appeared, as did herpes, polio, tick-borne fevers, giardiasis, and amebic dysentery. One admittedly controversial study by Henry Dobyns in Current Anthropology in 1966 later fleshed out over the years into his book, argued that extensive epidemics swept North America before Europeans arrived. As one authority summed up the research, 'Though the Old World was to contribute to its diseases, the New World certainly was not the Garden of Eden some have depicted.' As one might expect, others challenged Dobyns and the 'early epidemic' school, but the point remains that experts are divided. Many now discount the notion that huge epidemics swept through Central and North America; smallpox, in particular, did not seem to spread as a pandemic.

3. There is little evidence available for estimating the numbers of people lost in warfare prior to the Europeans because in general natives did not keep written records. Later, when whites could document oral histories during the Indian wars on the western frontier, they found that different tribes exaggerated their accounts of battles in totally different ways, depending on tribal custom. Some, who preferred to emphasize bravery over brains, inflated casualty numbers. Others, viewing large body counts as a sign of weakness, deemphasized their losses. What is certain is that vast numbers of natives were killed by other natives, and that only technological backwardness—the absence of guns, for example—prevented the numbers of natives killed by other natives from growing even higher.

4. Large areas of Mexico and the Southwest were depopulated more than a hundred years before the arrival of Columbus. According to a recent source, 'The majority of Southwesternists…believe that many areas of the Greater Southwest were abandoned or largely depopulated over a century before Columbus’s fateful discovery, as a result of climatic shifts, warfare, resource mismanagement, and other causes.' Indeed, a new generation of scholars puts more credence in early Spanish explorers’ observations of widespread ruins and decaying “great houses” that they contended had been abandoned for years.

5. European scholars have long appreciated the dynamic of small-state diplomacy, such as was involved in the Italian or German small states in the nineteenth century. What has been missing from the discussions about native populations has been a recognition that in many ways the tribes resembled the small states in Europe: they concerned themselves more with traditional enemies (other tribes) than with new ones (whites)."

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"When American history was first written, it featured and often celebrated politicians, military leaders, inventors, explorers, and other 'great men.' Textbooks in high school and college credited those goliaths with creating all the distinctive cultural and institutional characteristics of the United States. In this history from the top down, women, Indians, African Americans, immigrants, and ordinary workers—in other words, most Americans—seldom appeared. In the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of scholars began to place labor leaders, feminists, civil rights activists, and others who spoke on behalf of the people at the center of the story. This became known as history 'from the bottom up.' Yet more often than not, it seemed to me, the new stars of American history shared many of the cultural values and assumptions of the great men. They not only behaved like 'good' Americans but also worked to 'correct' the people they claimed to represent. They were not ordinary."

"When American history was first written, it featured and often celebrated politicians, military leaders, inventors, explorers, and other 'great men.' Textbooks in high school and college credited those goliaths with creating all the distinctive cultural and institutional characteristics of the United States. In this history from the top down, women, Indians, African Americans, immigrants, and ordinary workers—in other words, most Americans—seldom appeared. In the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of scholars began to place labor leaders, feminists, civil rights activists, and others who spoke on behalf of the people at the center of the story. This became known as history 'from the bottom up.' Yet more often than not, it seemed to me, the new stars of American history shared many of the cultural values and assumptions of the great men. They not only behaved like 'good' Americans but also worked to 'correct' the people they claimed to represent. They were not ordinary."

In 1492, a daring adventurer named Christopher Columbus set forth on a momentous expedition that unveiled the marvels of the Americas. This profound expedition brought about an extraordinary juncture in world history. The convergence of European explorers and the native inhabitants ignited a momentous collision of traditions, propelling lasting ramifications on societies and fundamentally shaping the fabric of civilizations.

The consequences of Columbus's arrival on the indigenous communities were undeniably significant and enduring. We're talking about violence, displacement, and utter cultural chaos. The Europeans brought along their fancy gadgets and brutal military tactics, and the natives found themselves facing an unfathomable force. The conflict became an unavoidable reality as the distribution of power was heavily skewed, resulting in the domination of numerous indigenous societies.

Yet, the tale did not culminate at that juncture. On the contrary, the European influence transcended mere territorial assertions; it forged ahead to displace the very roots of the indigenous communities. Coerced migration became the strategy, wresting away ancestral territories and time-honored customs, casting the native inhabitants into a state of profound ambiguity.

And let's not forget the insidious cultural invasion. The Europeans rolled in with their strange customs, incomprehensible languages, and newfangled religions, challenging the very essence of indigenous cultures. It was a full-on assault, and the consequences echoed through the generations.

We need to acknowledge the power of perspective to wrap our heads around the true extent of this historical mayhem. Traditional historical accounts have been shamelessly Eurocentric, sweeping the suffering and resilience of the indigenous folks under the proverbial rug. It's high time we break free from this biased narrative and start giving due credit to the perspectives of the marginalized.

To grasp the scope of indigenous losses, we must reckon with the devastating impact of diseases introduced by the Europeans. These viruses played a sick game of dominoes with indigenous populations, decimating their numbers and leaving a trail of destruction. We need to untangle this mess to see what was caused by the germs and what was fueled by the colonizers' nefarious ambitions.

Historians have often had a bad habit of glorifying "great men" while ignoring the struggles and contributions of the underdogs. the allure of history lies not solely in its prominent figures but also in the unsung heroes who play supporting roles. These obscured narratives harbor a trove of invaluable insights into the intricacies of American history, serving as poignant reminders that the superficial portrayals often leave much untold.

The saga of the Americas weaves a captivating tapestry of diverse experiences and interwoven histories, resembling a mosaic of intertwined tales that defy simplistic categorization. Appreciating this intricate web of stories demands a willingness to abandon rigid confines and embrace the boundless complexity inherent in the past.

Yet, as with any grand chronicle, challenges persist, posing barriers to unraveling the full extent of historical truth. We've got storytelling biases, conflicting viewpoints, and historical records that are anything but crystal clear. Some scholars argue against the idea of deliberate European genocide, highlighting the intricacies behind the decline of indigenous civilizations. We're swimming in a sea of misinformation, and it's up to historians to navigate these murky waters.

THE RUNDOWN

- In 1492, Christopher Columbus went on a big expedition to explore the Americas.

- This expedition brought together Europeans and native people, leading to clashes of cultures and societies.

- Columbus's arrival had significant and lasting consequences on the indigenous communities, including violence, displacement, and cultural chaos.

- The Europeans had advanced technology and military tactics, which led to domination over the native societies.

- European influence went beyond territorial claims; they displaced the roots of indigenous communities through forced migration.

- The Europeans also brought their customs, languages, and religions, challenging indigenous cultures.

- Traditional historical accounts have been Eurocentric, ignoring the suffering and resilience of indigenous people.

- Diseases introduced by the Europeans had a devastating impact on indigenous populations.

- It's important to acknowledge the perspectives of marginalized communities to understand the true extent of historical events.

- Historians should recognize the contributions of unsung heroes and not just focus on prominent figures.

- The history of the Americas is complex and diverse, with intertwined tales that defy simple categorization.

- There are challenges in understanding historical truth due to storytelling biases, conflicting viewpoints, and unclear records.

- Some scholars disagree with the idea of deliberate European genocide, emphasizing the complexities of the decline of indigenous civilizations.

- Historians must navigate through misinformation to uncover the past.

QUESTIONS

- How did the arrival of Christopher Columbus impact indigenous communities in the Americas, and why is it challenging to fully understand the repercussions?

- In what ways did the encounter between Europeans and indigenous peoples involve violence, displacement, and cultural turmoil? How did these factors contribute to the complexity of understanding the indigenous experience?

- Discuss the difficulties historians face in comprehending the loss and upheaval experienced by indigenous peoples. How do various perspectives and factors contribute to these challenges?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

In a captivating exploration of the elusive origins of the first Americans, the video navigates the turbulent waters of scholarly debate surrounding this ancient migration. Fueled by the groundbreaking discoveries in Folsom and Clovis, New Mexico, the Folsom and Clovis cultures emerged as early inhabitants of the Americas, thrusting the search into high gear. The video paints a vivid picture of the relentless pursuit of truth by unraveling the complex challenges of hunting mammoths and tracing the migration of our early ancestors from Siberia to Alaska. However, excavating the Monteverde archaeological site in Chile adds an unexpected twist to the narrative, subverting the prevailing Clovis-first theory. This enigmatic site presents a compelling case for humans settling in South America before the Clovis culture, shedding light on the fascinating culture and lifestyle of the Monteverde people. Wooden implements and sophisticated knowledge of herbal medicine unveil a tapestry of human ingenuity that defies conventional wisdom.

The profound implications of Monteverde's discovery reverberate through the annals of human history, prompting a reevaluation of the timing and routes of migration to the Americas. Genetic research lends credence to the notion of multiple migration events from Siberia. In contrast, the coastal migration theory gains momentum, tracing the intrepid footsteps of our ancestors along the western edges of North and South America. Meticulous archaeological work along the Alaskan and Canadian coasts corroborates this theory, and underwater studies in British Columbia solidify the presence of ancient humans along the northwest coast during the frigid embrace of the last ice age. As the video draws to a close, it becomes evident that the quest to unearth the origins of the first Americans continues to captivate and confound archaeologists. Each discovery shines a flickering light on ancient migration routes and the adaptive prowess of early humans. Perhaps, driven by the same insatiable curiosity that propels modern scientists, these brave pioneers embarked on their audacious odyssey to the new world, forever etching their story into the fabric of human history.

In a captivating exploration of the elusive origins of the first Americans, the video navigates the turbulent waters of scholarly debate surrounding this ancient migration. Fueled by the groundbreaking discoveries in Folsom and Clovis, New Mexico, the Folsom and Clovis cultures emerged as early inhabitants of the Americas, thrusting the search into high gear. The video paints a vivid picture of the relentless pursuit of truth by unraveling the complex challenges of hunting mammoths and tracing the migration of our early ancestors from Siberia to Alaska. However, excavating the Monteverde archaeological site in Chile adds an unexpected twist to the narrative, subverting the prevailing Clovis-first theory. This enigmatic site presents a compelling case for humans settling in South America before the Clovis culture, shedding light on the fascinating culture and lifestyle of the Monteverde people. Wooden implements and sophisticated knowledge of herbal medicine unveil a tapestry of human ingenuity that defies conventional wisdom.

The profound implications of Monteverde's discovery reverberate through the annals of human history, prompting a reevaluation of the timing and routes of migration to the Americas. Genetic research lends credence to the notion of multiple migration events from Siberia. In contrast, the coastal migration theory gains momentum, tracing the intrepid footsteps of our ancestors along the western edges of North and South America. Meticulous archaeological work along the Alaskan and Canadian coasts corroborates this theory, and underwater studies in British Columbia solidify the presence of ancient humans along the northwest coast during the frigid embrace of the last ice age. As the video draws to a close, it becomes evident that the quest to unearth the origins of the first Americans continues to captivate and confound archaeologists. Each discovery shines a flickering light on ancient migration routes and the adaptive prowess of early humans. Perhaps, driven by the same insatiable curiosity that propels modern scientists, these brave pioneers embarked on their audacious odyssey to the new world, forever etching their story into the fabric of human history.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- Precambian Era

- Palezoic Era

- Mesozoic Era

- Cenozoic Era

- Land Bridge

- The Archaic

- The Post-Archaic

- The White Myth

- Colonization of Hawaii

- Norse Colonization of North America

- Mississippian Culture

- The Hohokam Culture

- Iroquois Nation

- Birth of American Food

- The First Musicians

- Drugs and Mesoamerican Culture

- Sex and Mesoamerican Culture

- Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerican Culture

- Christopher Columbus

- The Columbia Exchange

- Ponce Deleon and Friends

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity: "Exploring Indigenous Communities in Pre-Columbian America"

Objective: The objective of this activity is to help students learn about the diverse indigenous communities that existed in pre-Columbian America and how they developed over time.

Activity:

Activity: Paleo-Indians Trading Activity

Objective: To simulate the trading practices and exchange of resources among the Paleo-Indians, and to understand the significance of trade in shaping the early history of North America.

Procedure:

Activity: "Exploring Indigenous Communities in Pre-Columbian America"

Objective: The objective of this activity is to help students learn about the diverse indigenous communities that existed in pre-Columbian America and how they developed over time.

Activity:

- Divide the class into small groups and assign each group a specific region of pre-Columbian America (e.g. the Great Plains, the Amazon, the Andes).

- Provide each group with a map of their assigned region and ask them to identify the indigenous communities that lived there during the time period covered in the course (4,600 Million BCE-1513 CE).

- Have each group research and present on one indigenous community that lived in their assigned region. The presentation should include information on the community's culture, economy, social organization, and interactions with other indigenous communities in the region.

- After each group has presented, ask the class to discuss the similarities and differences between the various indigenous communities in pre-Columbian America. Prompt the class to consider questions such as: How did the communities adapt to their environments? How did they trade and communicate with other communities? How did they form alliances and engage in conflicts with each other?

- Finally, have the class reflect on how their understanding of indigenous communities in pre-Columbian America differs from what they may have learned in the past. Ask students to consider how their knowledge of these communities can inform their understanding of US history more broadly.

Activity: Paleo-Indians Trading Activity

Objective: To simulate the trading practices and exchange of resources among the Paleo-Indians, and to understand the significance of trade in shaping the early history of North America.

Procedure:

- Divide the class into small groups of 4-5 students.

- Distribute the resources and index cards with descriptions of resources to each group.

- Explain that each group represents a different Paleo-Indian tribe, and that they are located in different regions of North America.

- Show the map of North America during the Paleo-Indian period, and explain that each group must trade with other tribes in order to obtain resources not available in their region.

- Allow the groups to interact and negotiate with each other to exchange resources. Encourage them to communicate using hand gestures and simple phrases, as this was likely how the Paleo-Indians communicated.

- After 10-15 minutes of trading, stop the activity and ask each group to share what resources they obtained and how they obtained them. Ask them to discuss how trade influenced their tribe's survival and way of life.

- Discuss as a class how the trading activity relates to the broader history of North America during the Paleo-Indian period. Ask students to reflect on how trade and exchange of resources shaped the development of societies during this time.

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

Earth's history is one hell of a wild ride, stretching back a jaw-dropping 4.6 billion years. We're talking ancient oceans, towering mountains, and volcanoes erupting with a vengeance, shaping this crazy planet over eons.

And then, like a thunderbolt from the blue, the Native Americans hit the stage, strutting their stuff on these lands for around 15,000 years. They left their mark. Culturally and spiritually, they had it going on. But the Europeans in the 16th century were ready to make their grand entrance. Colonies, democracy, individual rights— all of which sounds fancy. Sure, it brought some progress, but let's not forget the dark side. Mistreatment of Native Americans, the damn slavery of Africans, and resource exploitation that echoes through the annals of history.

History is a puzzle that'd give Sherlock Holmes a headache. We've got to play detective, sifting through ancient texts, collaborating with historians and journalists, and piecing together the scattered shards of the past. The Watergate scandal is a prime example of how collective efforts in investigative journalism can unveil the hidden truths and nail the bastards in power.

But let's get back to Columbus. He is frequently praised as a courageous adventurer, a trailblazer of the oceans. Nevertheless, this narrative has an untold depth akin to a labyrinth of unexpected intricacies. The encounter between Columbus and the indigenous folks was no walk in the park. It's not just about genocide; diseases brought over by the Europeans wreaked havoc on the native population. This was the price of exploration.

History tends to sideline the voices of those who weren't in the limelight. Throughout history, the voices of Native Americans and Africans have been obscured, and their narratives suppressed, all while the dominant storyline took precedence. The moment has arrived for a transformative shift. Let us take action to acknowledge and honor their rightful contributions and accomplishments.

Let us wholeheartedly embrace the intricacies that history unfolds. We must fearlessly plunge into its enigmatic abyss, confronting its glorious victories and heart-wrenching sorrows and encountering the extraordinary figures who have indelibly influenced our world. By grasping this grand tapestry's entirety, we gain wisdom from the errors of yesteryears, propelling us toward a radiant tomorrow. Together, we shall interweave our collective narrative, acknowledging imperfections and thus paving the way for a more enlightened and promising future.

Or, in other words:

- Earth is approximately 4.6 billion years old, with ancient oceans, mountains, and volcanoes shaping its landscape over time.

- Native Americans have inhabited the land for around 15,000 years, leaving a significant cultural impact.

- Europeans arrived in the 16th century, establishing colonies and introducing concepts like democracy, individual rights, and limited government.

- However, Europeans also engaged in the mistreatment of Native Americans, the enslavement of Africans, and resource exploitation, which still have lasting effects.

- Studying history requires detective-like investigation using primary sources and collaboration between historians and journalists.

- The Watergate scandal is an example of uncovering hidden truths through collective efforts.

- History is not a simple tale; the arrival of Columbus had complex consequences for indigenous communities, involving various perspectives and complexities beyond genocide.

- The diseases brought by Columbus had a profound impact on the indigenous population.

- It is essential to recognize the contributions of all individuals, including those often forgotten by mainstream history.

- Embracing the complexities of history promotes a more inclusive and accurate understanding of our shared past.

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #1

- Forum Discussion #1

- Forum Discussion #2

Forum Discussion #1

This first week I would like to take it easy, and get to know you better, please answer the following question with a one paragraph minimum:

What do you like about studying history? If you don't like history, what do you think the root cause is? Remember that you will be required to reply to at least two of your classmates.

Forum Discussion #2

The National Geographic YouTube channel is a digital platform that showcases captivating videos about the natural world, cultural diversity, scientific discoveries, and environmental issues. It provides a visually stunning and educational experience, allowing viewers to explore the wonders of our planet and gain a deeper understanding of the world around them. Watch the following video:

What do you like about studying history? If you don't like history, what do you think the root cause is? Remember that you will be required to reply to at least two of your classmates.

Forum Discussion #2

The National Geographic YouTube channel is a digital platform that showcases captivating videos about the natural world, cultural diversity, scientific discoveries, and environmental issues. It provides a visually stunning and educational experience, allowing viewers to explore the wonders of our planet and gain a deeper understanding of the world around them. Watch the following video:

Being a historian means you sometimes get to play detective. There are many mysteries yet to be solved, and maybe you are the person for the job! Please answer the following question:

What happened to the lost colony of Roanoke? Where did everyone go? Did they perish? What does "Croatoan" mean?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

The National Geographic video titled "What Happened to the Lost Colony at Roanoke?" takes on the enigmatic disappearance of the Roanoke colony in 1587. They were setting up shop on Roanoke Island, led by good ol' John White. But alas, facing their share of hurdles and squabbles, White hightailed it back to England in search of supplies, leaving behind about 115 settlers, including his kinfolk. After three long years, White returned to that forsaken isle, brimming with hope, only to find it utterly deserted. They vanished, poof! The video delves into the conjectures to untangle this riddle—did they tangle with the Native American tribes? Merge with their neighbors like milk in coffee? Or perhaps, beset by diseases, they succumbed to an untimely demise?

Ah, but fear not, my dear readers, for archaeologists and historians, the modern-day sleuths, enter the scene. They sniff around for clues; unearthing pottery fragments believed to be a Roanoke settler's handiwork. These findings shed some light on their intricate dance of coexistence and movement. But, alas, the puzzle persists. With a heavy sigh, the video concedes that the fog of uncertainty still shrouds the fate of the Roanoke colony. No resolute evidence, no smoking gun. And so, the brave researchers soldier on, exploring the island's nooks and crannies, parsing through ancient records, their determined hearts pulsating with the desire to peel back the layers of time and solve this lingering riddle, age-old and tantalizing.

What happened to the lost colony of Roanoke? Where did everyone go? Did they perish? What does "Croatoan" mean?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

The National Geographic video titled "What Happened to the Lost Colony at Roanoke?" takes on the enigmatic disappearance of the Roanoke colony in 1587. They were setting up shop on Roanoke Island, led by good ol' John White. But alas, facing their share of hurdles and squabbles, White hightailed it back to England in search of supplies, leaving behind about 115 settlers, including his kinfolk. After three long years, White returned to that forsaken isle, brimming with hope, only to find it utterly deserted. They vanished, poof! The video delves into the conjectures to untangle this riddle—did they tangle with the Native American tribes? Merge with their neighbors like milk in coffee? Or perhaps, beset by diseases, they succumbed to an untimely demise?

Ah, but fear not, my dear readers, for archaeologists and historians, the modern-day sleuths, enter the scene. They sniff around for clues; unearthing pottery fragments believed to be a Roanoke settler's handiwork. These findings shed some light on their intricate dance of coexistence and movement. But, alas, the puzzle persists. With a heavy sigh, the video concedes that the fog of uncertainty still shrouds the fate of the Roanoke colony. No resolute evidence, no smoking gun. And so, the brave researchers soldier on, exploring the island's nooks and crannies, parsing through ancient records, their determined hearts pulsating with the desire to peel back the layers of time and solve this lingering riddle, age-old and tantalizing.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- Anderson, Edward F. Peyote: The Divine Cactus. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996.

- Bakker, Robert T. The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. William Morrow & Co, 1986.

- Bauer, Susan Wise. The History of the Renaissance World: From the Rediscovery of Aristotle to the Conquest of Constantinople. W. W. Norton & Company, 2013.

- Barnosky, Anthony D. Heatstroke: Nature in an Age of Global Warming. Island Press, 2019.

- Bergreen, Laurence. Columbus: The Four Voyages. Penguin Books, 2011.

- Berrin, Kathleen, and Esther Pasztory, eds. Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods. Thames & Hudson, 1993.

- Brusatte, Stephen L. The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World. William Morrow, 2018.

- Carrasco, David. "City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization." Beacon Press, 2000.

- Condie, Kent C. "Plate Tectonics and Crustal Evolution." Elsevier, 2018.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1972.

- Crèvecoeur, J. Hector St. John. Travels in Upper Pennsylvania and the State of New York. 1801.

- Cronin, Thomas M. Paleoclimates: Understanding Climate Change Past and Present. Columbia University Press, 2010.

- Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.

- Dixon, E. James. Quest for the Origins of the First Americans. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

- Fenton, William N. The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

- Fitzhugh, William W., and Elisabeth I. Ward. Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000.

- Fowler, Melvin L. Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. University of Illinois Press, 1997.

- Grotzinger, John P., et al. Understanding Earth. 7th ed., W.H. Freeman and Company, 2019.

- Hatcher, John Bell, et al. The Ceratopsia. U.S. Geological Survey, 1907.

- Hoffman, Paul E. Florida's Frontiers. Indiana University Press, 2002.

- Justice, Noel D. Stone Age Spear and Arrow Points of the Midcontinental and Eastern United States: A Modern Survey and Reference. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

- Kehoe, Thomas F. America Before the European Invasions. Rutledge, 2016.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton. "On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact." University of California Press, 2000.

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. "Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants." Milkweed Editions, 2013.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson. "The Hawaiian Kingdom: Volume 1, Foundation and Transformation." University of Hawaii Press, 1938.

- Levin, Harold L. The Earth Through Time. 11th ed., Wiley, 2017.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. "They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School." University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- MacFadden, Bruce J. Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Mann, Charles C. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York: Vintage Books, 2012.

- Milanich, Jerald T. 1994. "Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida." University Press of Florida.

- Milner, George R. The Moundbuilders: Ancient Peoples of Eastern North America. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

- Mowat, Farley. Westviking: The Ancient Norse in Greenland and North America. McClelland and Stewart, 1965.

- Pálsson, Hermann, and Edwards, Paul. The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America. Penguin Classics, 1965.

- Pauketat, Timothy R. Cahokia: Ancient America's Great City on the Mississippi. Viking, 2009.

- Phillips, William D., Jr. Slavery from Roman Times to the Early Transatlantic Trade. University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

- Prothero, Donald R. The Eocene-Oligocene Transition: Paradise Lost. Columbia University Press, 1994.

- Raup, David M. "Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck?" W.W. Norton & Company, 1992.

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Richter, Daniel K. The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization. University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

- Sahlins, Marshall. "Islands of History." University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Sassaman, Kenneth E. 2004. "Complex Hunter-Gatherers in Evolution and History: A North American Perspective." Journal of Archaeological Research 12 (3): 227-280.

- Schultes, Richard Evans, and Albert Hofmann. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. Healing Arts Press, 1992.

- Smith, Andrew F. "Eating History: Thirty Turning Points in the Making of American Cuisine." Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Taube, Karl A. "Aztec and Maya Myths." University of Texas Press, 1993.

- Tannahill, Reay. "Food in History." Three Rivers Press, 1988.

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005.

- Mintz, Steven, and Susan Kellogg. Domestic Revolutions: A Social History of American Family Life. Free Press, 1988.

- Schwartz, Barry, and Howard Schuman. The American People and Their Education:

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.