HST 201 Module #5

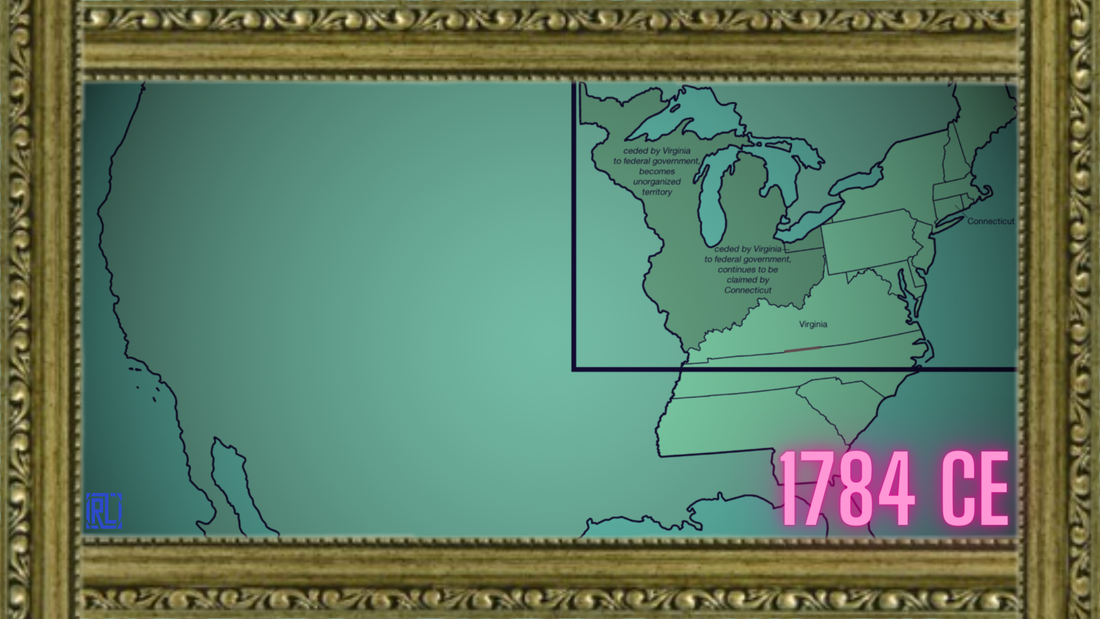

Module Five: The Revolution Is At Hand! (1775 CE- 1784 CE)

The years 1775 CE-1784 are a critical period in US history, commonly referred to as the American Revolution. This period marks the beginning of the United States as an independent nation and the end of British colonial rule. The American Revolution was a tumultuous time that brought about significant social, economic, and political changes. The purpose of this essay is to examine the events of this period, their relevance today, and why it is crucial to study this subject.

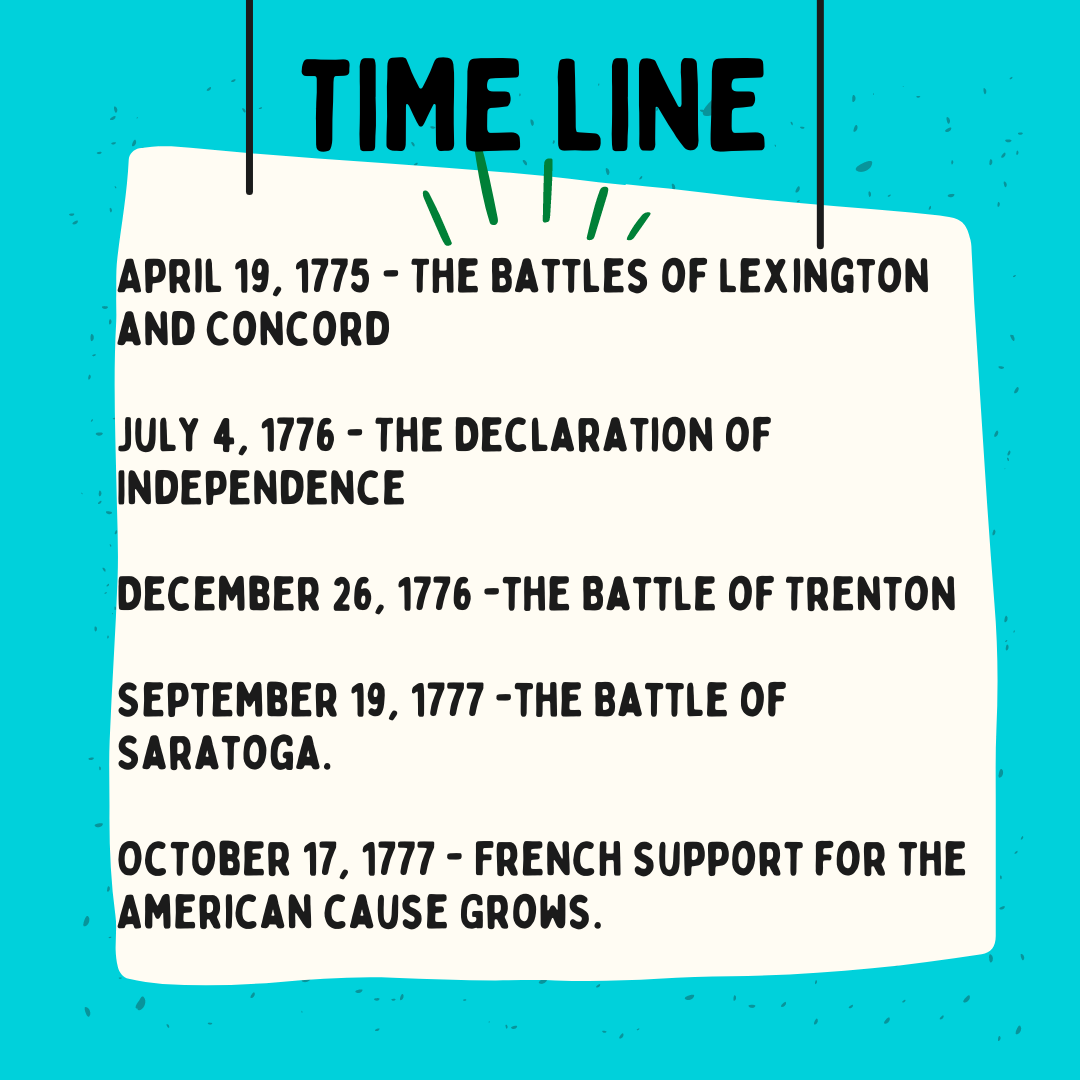

The American Revolution began in 1775 when British troops clashed with colonial militias at Lexington and Concord. The conflict escalated, and on July 4, 1776, the thirteen colonies declared their independence from Britain with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The war continued for several years, with the Americans receiving military and financial support from France, Spain, and the Netherlands. The war came to an end in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which recognized the United States as a sovereign nation.

The American Revolution brought about significant changes in American society. The colonists had fought for their rights and freedoms, and this struggle for liberty was reflected in the new nation's founding principles. The United States became a republic, with a government based on the consent of the governed. The revolution also led to the abolition of slavery in the northern states, and the Founding Fathers included language in the Constitution that eventually led to the end of slavery in the United States.

The American Revolution had both positive and negative consequences. The positive outcomes included the establishment of a democratic government, the abolition of slavery, and the creation of a new nation based on the principles of liberty and justice. The revolution also led to an expansion of American territory, as the United States acquired new land from France and Spain. However, the war also had negative consequences, such as the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans, the economic hardship caused by the war, and the exclusion of women and minorities from full participation in the new nation.

The events of 1775 CE-1784 have significant relevance today. The principles of democracy, liberty, and justice that were established during the American Revolution are still central to American society. The revolution also serves as an inspiration to other nations that are struggling for their rights and freedoms. The study of this period helps us to understand the origins of American democracy and the struggles and sacrifices that were made to create a new nation. It also allows us to reflect on the progress that has been made since then and the work that still needs to be done to ensure that all Americans are treated equally and have access to the same rights and opportunities.

In conclusion, the years 1775 CE-1784 are a crucial period in US history, marking the beginning of the United States as an independent nation. The American Revolution was a time of significant change, with positive outcomes such as the establishment of a democratic government and the abolition of slavery, but also negative consequences such as the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans. The study of this period is crucial because it helps us to understand the origins of American democracy, the struggles and sacrifices that were made to create a new nation, and the ongoing work that is necessary to ensure that all Americans are treated equally and have access to the same rights and opportunities.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The years 1775 CE-1784 are a critical period in US history, commonly referred to as the American Revolution. This period marks the beginning of the United States as an independent nation and the end of British colonial rule. The American Revolution was a tumultuous time that brought about significant social, economic, and political changes. The purpose of this essay is to examine the events of this period, their relevance today, and why it is crucial to study this subject.

The American Revolution began in 1775 when British troops clashed with colonial militias at Lexington and Concord. The conflict escalated, and on July 4, 1776, the thirteen colonies declared their independence from Britain with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The war continued for several years, with the Americans receiving military and financial support from France, Spain, and the Netherlands. The war came to an end in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which recognized the United States as a sovereign nation.

The American Revolution brought about significant changes in American society. The colonists had fought for their rights and freedoms, and this struggle for liberty was reflected in the new nation's founding principles. The United States became a republic, with a government based on the consent of the governed. The revolution also led to the abolition of slavery in the northern states, and the Founding Fathers included language in the Constitution that eventually led to the end of slavery in the United States.

The American Revolution had both positive and negative consequences. The positive outcomes included the establishment of a democratic government, the abolition of slavery, and the creation of a new nation based on the principles of liberty and justice. The revolution also led to an expansion of American territory, as the United States acquired new land from France and Spain. However, the war also had negative consequences, such as the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans, the economic hardship caused by the war, and the exclusion of women and minorities from full participation in the new nation.

The events of 1775 CE-1784 have significant relevance today. The principles of democracy, liberty, and justice that were established during the American Revolution are still central to American society. The revolution also serves as an inspiration to other nations that are struggling for their rights and freedoms. The study of this period helps us to understand the origins of American democracy and the struggles and sacrifices that were made to create a new nation. It also allows us to reflect on the progress that has been made since then and the work that still needs to be done to ensure that all Americans are treated equally and have access to the same rights and opportunities.

In conclusion, the years 1775 CE-1784 are a crucial period in US history, marking the beginning of the United States as an independent nation. The American Revolution was a time of significant change, with positive outcomes such as the establishment of a democratic government and the abolition of slavery, but also negative consequences such as the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans. The study of this period is crucial because it helps us to understand the origins of American democracy, the struggles and sacrifices that were made to create a new nation, and the ongoing work that is necessary to ensure that all Americans are treated equally and have access to the same rights and opportunities.

THE RUNDOWN

- 1775 CE-1784 marks the American Revolution and the beginning of the United States as an independent nation.

- The American Revolution brought significant changes to American society, including the establishment of a democratic government, abolition of slavery in northern states, and expansion of American territory.

- The Revolution had both positive and negative consequences, such as the displacement and mistreatment of Native Americans and exclusion of women and minorities from full participation in the new nation.

- The principles of democracy, liberty, and justice established during the Revolution remain central to American society today.

- Studying this period helps us understand the origins of American democracy, the struggles and sacrifices made to create a new nation, and the work still necessary to ensure all Americans are treated equally and have access to the same rights and opportunities.

QUESTIONS

- How did the American Revolution impact the lives of women, Native Americans, and enslaved people, and what were their experiences during this period?

- How did the American Revolution influence the development of the United States Constitution, and what key principles were established during this period?

- How did the American Revolution impact economic and social changes in the United States, and how did these changes shape the nation's future?

#5 History in Not Monolithic

Pay attention: this next part is crucial for you to understand the nuances of history. This is most likely my most important rule. Ultimately, I tell my students at the beginning of every semester. Rule Number Five of History is History is not monolithic. It is told through countless eyes and countless lenses. Unfortunately, this is the first thing to go when organizing historical thoughts. When building a timeline of events, the historian must separate the vital from the trivial and mundane. However, this becomes challenging to do objectively. Like it or not, our worldview decides what is important to us. And our worldview is formed from our backgrounds and our values. Knowing this, we tend to have our history spoon-fed from a specific demographic, generally upper-class white Christian men. Before you cancel me, I must stress that this is not an attack but merely an observation. Those stories are important. That history must be preserved and retold. But what about other demographics? When drudging through American history, we spend much of our time dissecting the slave economy of the 19th century, the butchering and abuses against the native Americans, and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Again, all pivotal moments in time and critical for understanding our past. But there is so much more out there that needs to be addressed.

Asian American history and Latino history are, for the most part, nonexistent. Gay and Trans accounts are forgotten. Who was the first Muslim in the new world? The first Asians? Heck, what about the sports and games people played in the 17th century? All these concepts and stories beg to be addressed. I knew that publishers are limited to what they can include, especially at the hands of special interest groups and federal mandates in a textbook format. I am not tethered to that. This class can be whatever we shaped it into. It can grow and breathe as needed. And it will speak for the voiceless.

You see, history is not like a straight line. It's more like a big ol' plate of spaghetti. All tangled up, and different folks see different things in it. Take the whole colonization thing in America, the settlers saw it as a time of progress and expansion, but for the Native Americans, it was more like a big ol' heap of oppression. The same thing happened with the Civil Rights Movement. It was progress for some folks and a lot of violence and resistance for others. And it isn't just the past; it's the present, too. We keep reinterpreting and reevaluating things as new information comes to light. Like, the history of the women's suffrage movement, we used to see it from one angle, but now we're seeing it from all different perspectives, including the ones that were left out before—the same thing with the history of the transatlantic slave trade. We're seeing it from the point of view of the enslaved people, not just the slave traders.

So, history is not monolithic, it's a big ol' plate of spaghetti, and if we want to understand it, we got to look at it from all different angles. If we do, we'll get all the important stuff.

THE RUNDOWN

STATE OF THE UNION

Pay attention: this next part is crucial for you to understand the nuances of history. This is most likely my most important rule. Ultimately, I tell my students at the beginning of every semester. Rule Number Five of History is History is not monolithic. It is told through countless eyes and countless lenses. Unfortunately, this is the first thing to go when organizing historical thoughts. When building a timeline of events, the historian must separate the vital from the trivial and mundane. However, this becomes challenging to do objectively. Like it or not, our worldview decides what is important to us. And our worldview is formed from our backgrounds and our values. Knowing this, we tend to have our history spoon-fed from a specific demographic, generally upper-class white Christian men. Before you cancel me, I must stress that this is not an attack but merely an observation. Those stories are important. That history must be preserved and retold. But what about other demographics? When drudging through American history, we spend much of our time dissecting the slave economy of the 19th century, the butchering and abuses against the native Americans, and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Again, all pivotal moments in time and critical for understanding our past. But there is so much more out there that needs to be addressed.

Asian American history and Latino history are, for the most part, nonexistent. Gay and Trans accounts are forgotten. Who was the first Muslim in the new world? The first Asians? Heck, what about the sports and games people played in the 17th century? All these concepts and stories beg to be addressed. I knew that publishers are limited to what they can include, especially at the hands of special interest groups and federal mandates in a textbook format. I am not tethered to that. This class can be whatever we shaped it into. It can grow and breathe as needed. And it will speak for the voiceless.

You see, history is not like a straight line. It's more like a big ol' plate of spaghetti. All tangled up, and different folks see different things in it. Take the whole colonization thing in America, the settlers saw it as a time of progress and expansion, but for the Native Americans, it was more like a big ol' heap of oppression. The same thing happened with the Civil Rights Movement. It was progress for some folks and a lot of violence and resistance for others. And it isn't just the past; it's the present, too. We keep reinterpreting and reevaluating things as new information comes to light. Like, the history of the women's suffrage movement, we used to see it from one angle, but now we're seeing it from all different perspectives, including the ones that were left out before—the same thing with the history of the transatlantic slave trade. We're seeing it from the point of view of the enslaved people, not just the slave traders.

So, history is not monolithic, it's a big ol' plate of spaghetti, and if we want to understand it, we got to look at it from all different angles. If we do, we'll get all the important stuff.

THE RUNDOWN

- History isn't just one version told by one group of people. It's said in different ways, depending on who is telling it.

- What we care about in history is shaped by our experiences and origins.

- Usually, history is taught by wealthy white Christian men, but it's essential to learn about the experiences of other groups too.

- We need to learn about the history of different groups like Asian Americans, Latinos, Gay/Trans people, sports, games, and others.

- Think of history like a plate of spaghetti, with many interpretations and viewpoints that change as we learn more.

- To understand history, we must look at it from many different perspectives.

STATE OF THE UNION

1784: a year of transformation and turbulence, where the world teetered on the brink of monumental change. The United States, freshly emancipated from the bruises of the American Revolutionary War, awkwardly flexing its nascent independence under the ineffectual Articles of Confederation, dreaming of the U.S. Constitution yet to be born. Across the Atlantic, Europe buzzes with the residual shockwaves of the American Revolution, with France teetering on fiscal ruin and social upheaval, Enlightenment ideals simmering beneath the surface, and Britain nursing its post-revolutionary wounds in the cold, mechanical embrace of the Industrial Revolution. Enlightenment thinkers pontificated in intellectual salons, while the pioneering spirit of Benjamin Franklin sparked curiosity with his electrical experiments, a testament to the power of individual action in shaping history. Neoclassical art and architecture starkly contrast with the unpredictable world outside, where life is gritty and grim, life expectancy low, and medical knowledge a crude blend of superstition and developing science. The transatlantic slave trade grinds on with ruthless efficiency, African societies fracture under European colonization, and the British East India Company tightens its grip on India. The Ottoman Empire shows cracks, Latin America whispers of revolution, and the globe clings to old traditions while the new world claws its way into existence. This tapestry of contradiction and anticipation set the stage for political, social, and industrial revolutions that will blend the sublime with the absurd in a symphony of progress and pain.

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- RPTM #017: Smallpox, Women, Blacks and Latinos in the Revolution (39:49)

- RPTM #018: Jews, Muslims, Sex, The Fourth of July, and the Declaration of Independence (35:25)

- RPTM #019 von Stueben, Gadsden, Yankee Doodle, and the End of the War (38:00)

- RPTM #020 The Fallout from the Revolution, the Founding Fathers, And the Treaty of Six Nations (32:55)

The Reading section—a realm where our aspirations of enlightenment often clash with the harsh realities of procrastination and the desperate reliance on Google. We soldier on through dense texts, promised 'broadening perspectives' but often wrestling with existential dread and academic pressure. With a healthy dose of sarcasm and a strong cup of coffee, I'll be your guide on this wild journey from dusty tomes to the murky depths of postmodernism. In the midst of all the pretentious prose, there's a glimmer of insight: we're all in this together, united in our struggle to survive without losing our sanity.

READING

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

RUNDOWN

READING

- Carnes Chapter 5: “The American Revolution”

- “Bloody Shrapnel Discovered at Monmouth Battlefield; First of its Kind” by Jerry Carino

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

RUNDOWN

- Tensions between the American colonies and Britain grew due to British taxes and laws, such as the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts.

- Colonists protested through actions like the Boston Tea Party and formed groups like the Sons of Liberty.

- The first battles of the American Revolution occurred in 1775 at Lexington and Concord, leading to open warfare between the colonies and Britain.

- The Second Continental Congress met and created the Continental Army, appointing George Washington as its leader.

- In 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, written mainly by Thomas Jefferson, officially breaking away from British rule.

- Key battles included the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Siege of Boston, and the Battle of Saratoga, which was a turning point because it convinced France to support the American cause.

- The harsh winter at Valley Forge tested the Continental Army’s resolve, but training and discipline improved under Baron von Steuben.

- France, and later Spain and the Netherlands, provided crucial military and financial support to the American colonies.

- The war shifted to the South, with significant battles like Camden and Cowpens.

- The British defeat at Yorktown in 1781, where General Cornwallis surrendered to Washington, effectively ended major fighting.

- The war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which recognized American independence and set the nation’s borders.

- The Revolution led to the creation of the United States of America and inspired democratic ideas around the world.

- Challenges remained, including building a new government and addressing issues like slavery and Native American relations.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... By this time there was already a powerful sentiment for independence. Resolutions adopted in North Carolina in May of 1776, and sent to the Continental Congress, declared independence of England, asserted that all British law was null and void, and urged military preparations. About the same time, the town of Maiden, Massachusetts, responding to a request from the Massachusetts House of Representatives that all towns in the state declare their views on independence, had met in town meeting and unanimously called for independence: '. . . we therefore renounce with disdain our connexion with a kingdom of slaves; we bid a final adieu to Britain.'

'When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands . . . they should declare the causes....' This was the opening of the Declaration of Independence. Then, in its second paragraph, came the powerful philosophical statement:

We hold these truths to he self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments arc instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government....

It then went on to list grievances against the king, 'a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.' The list accused the king of dissolving colonial governments, controlling judges, sending 'swarms of Officers to harass our people,' sending in armies of occupation, cutting off colonial trade with other parts of the world, taxing the colonists without their consent, and waging war against them, 'transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny.'

All this, the language of popular control over governments, the right of rebellion and revolution, indignation at political tyranny, economic burdens, and military attacks, was language well suited to unite large numbers of colonists, and persuade even those who had grievances against one another to turn against England.

Some Americans were clearly omitted from this circle of united interest drawn by the Declaration of Independence: Indians, black slaves, women. Indeed, one paragraph of the Declaration charged the King with inciting slave rebellions and Indian attacks:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst as, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions..."

"... By this time there was already a powerful sentiment for independence. Resolutions adopted in North Carolina in May of 1776, and sent to the Continental Congress, declared independence of England, asserted that all British law was null and void, and urged military preparations. About the same time, the town of Maiden, Massachusetts, responding to a request from the Massachusetts House of Representatives that all towns in the state declare their views on independence, had met in town meeting and unanimously called for independence: '. . . we therefore renounce with disdain our connexion with a kingdom of slaves; we bid a final adieu to Britain.'

'When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands . . . they should declare the causes....' This was the opening of the Declaration of Independence. Then, in its second paragraph, came the powerful philosophical statement:

We hold these truths to he self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments arc instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government....

It then went on to list grievances against the king, 'a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.' The list accused the king of dissolving colonial governments, controlling judges, sending 'swarms of Officers to harass our people,' sending in armies of occupation, cutting off colonial trade with other parts of the world, taxing the colonists without their consent, and waging war against them, 'transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny.'

All this, the language of popular control over governments, the right of rebellion and revolution, indignation at political tyranny, economic burdens, and military attacks, was language well suited to unite large numbers of colonists, and persuade even those who had grievances against one another to turn against England.

Some Americans were clearly omitted from this circle of united interest drawn by the Declaration of Independence: Indians, black slaves, women. Indeed, one paragraph of the Declaration charged the King with inciting slave rebellions and Indian attacks:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst as, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... It goes without saying, of course, that most of these men were steeped in the traditions and teachings of Christianity—almost half the signers of the Declaration of Independence had some form of seminary training or degree. John Adams, certainly and somewhat derogatorily viewed by his contemporaries as the most pious of the early Revolutionaries, claimed that the Revolution 'connected, in one indissoluble bond, the principles of civil government with the principles of Christianity.' John’s cousin Sam cited passage of the Declaration as the day that the colonists 'restored the Sovereign to Whom alone men ought to be obedient.' John Witherspoon’s influence before and after the adoption of the Declaration was obvious, but other well-known patriots such as John Hancock did not hesitate to echo the reliance on God. In short, any reading of the American Revolution from a purely secular viewpoint ignores a fundamentally Christian component of the Revolutionary ideology.

One can understand how scholars could be misled on the importance of religion in daily life and political thought. Data on religious adherence suggests that on the eve of the Revolution perhaps no more than 20 percent of the American colonial population was 'churched.' That certainly did not mean they were not God-fearing or religious. It did reflect, however, a dominance of the three major denominations—Congregationalist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal—that suddenly found themselves challenged by rapidly rising new groups, the Baptists and Methodists. Competition from the new denominations proved so intense that clergy in Connecticut appealed to the assembly for protection against the intrusions of itinerant ministers. But self-preservation also induced church authorities to lie about the presence of other denominations, claiming that 'places abounding in Baptists or Methodists were unchurched.' In short, while church membership rolls may have indicated low levels of religiosity, a thriving competition for the 'religious market' had appeared, and contrary to the claims of many that the late 1700s constituted an ebb in American Christianity, God was alive and well—and fairly popular! "

"... It goes without saying, of course, that most of these men were steeped in the traditions and teachings of Christianity—almost half the signers of the Declaration of Independence had some form of seminary training or degree. John Adams, certainly and somewhat derogatorily viewed by his contemporaries as the most pious of the early Revolutionaries, claimed that the Revolution 'connected, in one indissoluble bond, the principles of civil government with the principles of Christianity.' John’s cousin Sam cited passage of the Declaration as the day that the colonists 'restored the Sovereign to Whom alone men ought to be obedient.' John Witherspoon’s influence before and after the adoption of the Declaration was obvious, but other well-known patriots such as John Hancock did not hesitate to echo the reliance on God. In short, any reading of the American Revolution from a purely secular viewpoint ignores a fundamentally Christian component of the Revolutionary ideology.

One can understand how scholars could be misled on the importance of religion in daily life and political thought. Data on religious adherence suggests that on the eve of the Revolution perhaps no more than 20 percent of the American colonial population was 'churched.' That certainly did not mean they were not God-fearing or religious. It did reflect, however, a dominance of the three major denominations—Congregationalist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal—that suddenly found themselves challenged by rapidly rising new groups, the Baptists and Methodists. Competition from the new denominations proved so intense that clergy in Connecticut appealed to the assembly for protection against the intrusions of itinerant ministers. But self-preservation also induced church authorities to lie about the presence of other denominations, claiming that 'places abounding in Baptists or Methodists were unchurched.' In short, while church membership rolls may have indicated low levels of religiosity, a thriving competition for the 'religious market' had appeared, and contrary to the claims of many that the late 1700s constituted an ebb in American Christianity, God was alive and well—and fairly popular! "

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

".. Many generations before feminists made women’s work in the 'public sphere' acceptable, female inhabitants of the early, freewheeling American cities worked in every imaginable profession. They were blacksmiths, butchers, distillers, dockworkers, hucksters, innkeepers, manual laborers, mariners, pawnbrokers, peddlers, plasterers, printers, skinners, and wine-makers. Many women in the eighteenth century not only worked in what later became exclusively male occupations but also owned a great number of businesses that would soon be deemed grossly unfeminine. Hannah Breintnall was typical of a class of female entrepreneurs who benefited from the looseness of gender norms in early America. When her husband died, Breintnall opened the Hen and Chickens Tavern on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, not far from the residences of many of the Founding Fathers and the State House where the United States was made. The fact that a woman owned the bar did not stop the sheriff from holding public auctions at the Hen and Chickens, nor did it stop patrons from making Breintnall, by the time she died in 1770, one of the wealthiest inhabitants of the city. In Philadelphia alone, in the two decades before the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, at least 110 women worked as tavern keepers, and more than 75 operated retail shops of various sorts. Historians have estimated that as many as half of all shops in early American cities were owned and operated by women. Moral judgments appear to have

had little effect on these renegade women. Many operated houses of prostitution inside their taverns. Margaret Cook, one of these shameless tavern owners, should be celebrated by every American woman who values her freedom. In 1741 Cook was brought into court on charges that she welcomed as patrons 'Whores, Vagabonds, and divers Idle Men of a suspected bad conversation' and that she 'continually did keep bad order and Government.' Twenty years later, apparently unchastened, Cook returned to court to face the very same charges."

".. Many generations before feminists made women’s work in the 'public sphere' acceptable, female inhabitants of the early, freewheeling American cities worked in every imaginable profession. They were blacksmiths, butchers, distillers, dockworkers, hucksters, innkeepers, manual laborers, mariners, pawnbrokers, peddlers, plasterers, printers, skinners, and wine-makers. Many women in the eighteenth century not only worked in what later became exclusively male occupations but also owned a great number of businesses that would soon be deemed grossly unfeminine. Hannah Breintnall was typical of a class of female entrepreneurs who benefited from the looseness of gender norms in early America. When her husband died, Breintnall opened the Hen and Chickens Tavern on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, not far from the residences of many of the Founding Fathers and the State House where the United States was made. The fact that a woman owned the bar did not stop the sheriff from holding public auctions at the Hen and Chickens, nor did it stop patrons from making Breintnall, by the time she died in 1770, one of the wealthiest inhabitants of the city. In Philadelphia alone, in the two decades before the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, at least 110 women worked as tavern keepers, and more than 75 operated retail shops of various sorts. Historians have estimated that as many as half of all shops in early American cities were owned and operated by women. Moral judgments appear to have

had little effect on these renegade women. Many operated houses of prostitution inside their taverns. Margaret Cook, one of these shameless tavern owners, should be celebrated by every American woman who values her freedom. In 1741 Cook was brought into court on charges that she welcomed as patrons 'Whores, Vagabonds, and divers Idle Men of a suspected bad conversation' and that she 'continually did keep bad order and Government.' Twenty years later, apparently unchastened, Cook returned to court to face the very same charges."

The American Revolution, a turning point in the grand tapestry of time, arose from an indomitable desire for liberation that found its ultimate expression in the hallowed words of the Declaration of Independence. This humble essay embarks on a voyage to unravel the enduring importance of studying the Revolution in our present day, unveiling the fervent cries for self-governance voiced in the resolutions of the colonial era, the exclusionary shades that dimmed the brilliance of the Declaration, the ethereal threads of faith woven into the Revolution's fabric, and the remarkable metamorphosis ignited by the unyielding spirit of women. Through a meticulous expedition into historical vignettes, this humble piece of prose endeavors to illuminate the duality of this consequential chapter in the annals of American history, casting light upon its triumphs and tribulations.

The American Revolution, my friends, was a tumultuous and audacious journey toward liberation. Fueled by an unwavering hunger for independence, it sprouted from the seeds of dissent planted across the colonies. Take, for instance, the Virginia Resolves of 1765, a bold proclamation that rallied the colonists to assert their English rights and defy the audacity of the British Parliament to levy taxes without their consent. Likewise, the Massachusetts Circular Letter of 1768 served as a spirited testament to the colonists' vehement opposition to British policies, fearlessly asserting their unwavering determination to govern themselves. These powerful resolutions acted as the connective tissue binding the colonies together, forging a defiant collective spirit that England could not ignore. And so, my fellow adventurers, in the fateful year of 1776, this fiery rebellion reached its crescendo, giving birth to the irrevocable Declaration of Independence. This clarion call echoed through the annals of history, forever etching the indomitable spirit of freedom onto the very fabric of America.

The Declaration of Independence hailed as the cornerstone of colonial unity, becomes a perplexing document when examined through the kaleidoscope of marginalized voices. It is an account that brazenly sidesteps the acknowledgment of certain groups, such as Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women, casting them into the shadows of disregard. Within its carefully crafted prose, the Declaration dare not venture beyond the derogatory confines of "merciless Indian savages," thus perpetuating stereotypes and systematically denying these individuals their inherent rights. A paradox arises when we juxtapose the lofty ideals of liberty with the disheartening reality of continued enslavement for enslaved Black people as if freedom could somehow coexist with such abject subjugation. And let us not forget the absence of women, relegated to a mere peripheral role while the Revolution gallantly championed the rights of their male counterparts. These exclusions provide a stark reminder of the boundaries that impeded the revolutionary aspirations, serving as a stark testament to the arduous path still awaiting traversing to achieve genuine equality and comprehensive inclusivity.

Like a divine tapestry woven with threads of Christian conviction, the American Revolution fused religious fervor with revolutionary fervor. Those who dared to dream of independence saw their struggle as a holy crusade, their righteous cause etched in the fabric of freedom and bestowed by a higher power. In this turbulent era, influential spiritual leaders emerged as catalysts, their sermons and writings igniting the flames of inspiration within the colonists' hearts. The Reverend Jonathan Mayhew and the Reverend John Witherspoon stood at the forefront, casting their theological weight to unite and encourage the masses. Through this harmonious union of religious devotion and the unyielding fire of Revolution, the colonists stood resolute, fortified by a faith that knew no bounds.

The American Revolution turned the whole damn thing on its head, shaking those rigid gender roles to their core and carving out some space for the ladies in early American society. Sure, they were mainly told to sit down and shut up regarding politics and warfare. These women weren't having any of that. Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and Deborah Sampson, to name a few, weren't afraid to get their hands dirty. They took up the pen, poured their hearts out in political writings, and raised their voices in advocacy, and some of them even slapped on a pair of pants and went to war disguised as men. These gutsy moves opened the floodgates for future generations of women, sparking some fiery debates about their rights and where they belonged in this crazy society of ours.

Ah, the wondrous positives bestowed upon the land of the free! In the grand theater of history, the American Revolution, that valiant uprising against British dominion, bequeathed unto the newborn nation the coveted mantle of independence. Thus, a land untethered from the yoke of tyranny emerged, its revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and self-governance seared into the very fabric of its being. These audacious principles, birthed upon the birth of a nation, transcended the boundaries of time and space, encouraging subsequent democratic endeavors across the globe. From the blood-soaked streets of Paris during the French Revolution to the emotional struggles for emancipation from colonial oppression, the flame of inspiration ignited by the American Revolution continues to illuminate the path toward freedom and equality for all who dare to challenge the status quo.

For all its grand promises, the Revolution tragically fell short in eradicating exclusions and inequalities that plagued marginalized communities like Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women. Liberty's battle cry rang hollow as the despicable institution of slavery persisted, overshadowing the lofty ideals championed during those turbulent times. America, stained by the horror of slavery, would endure a protracted and contentious fight before finally breaking free from its clutches.

The study of the American Revolution today is vital if we aim to grasp the intricate historical mechanisms that molded the inception of the United States. Delving into this pivotal era allows us to scrutinize the formidable yearning for independence, the inherent disparities and imbalances lurking within the very fabric of the Declaration of Independence, the pervasive religious undertones that permeated the Revolution, and the revolutionary impact of women's engagement. By meticulously scrutinizing both the triumphs and the flaws of this momentous event, we glean valuable insights into the intricate complexities and inherent contradictions that defined the Revolution, consequently compelling us to introspectively grapple with the persistent obstacles of establishing a comprehensive and egalitarian society.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The American Revolution, my friends, was a tumultuous and audacious journey toward liberation. Fueled by an unwavering hunger for independence, it sprouted from the seeds of dissent planted across the colonies. Take, for instance, the Virginia Resolves of 1765, a bold proclamation that rallied the colonists to assert their English rights and defy the audacity of the British Parliament to levy taxes without their consent. Likewise, the Massachusetts Circular Letter of 1768 served as a spirited testament to the colonists' vehement opposition to British policies, fearlessly asserting their unwavering determination to govern themselves. These powerful resolutions acted as the connective tissue binding the colonies together, forging a defiant collective spirit that England could not ignore. And so, my fellow adventurers, in the fateful year of 1776, this fiery rebellion reached its crescendo, giving birth to the irrevocable Declaration of Independence. This clarion call echoed through the annals of history, forever etching the indomitable spirit of freedom onto the very fabric of America.

The Declaration of Independence hailed as the cornerstone of colonial unity, becomes a perplexing document when examined through the kaleidoscope of marginalized voices. It is an account that brazenly sidesteps the acknowledgment of certain groups, such as Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women, casting them into the shadows of disregard. Within its carefully crafted prose, the Declaration dare not venture beyond the derogatory confines of "merciless Indian savages," thus perpetuating stereotypes and systematically denying these individuals their inherent rights. A paradox arises when we juxtapose the lofty ideals of liberty with the disheartening reality of continued enslavement for enslaved Black people as if freedom could somehow coexist with such abject subjugation. And let us not forget the absence of women, relegated to a mere peripheral role while the Revolution gallantly championed the rights of their male counterparts. These exclusions provide a stark reminder of the boundaries that impeded the revolutionary aspirations, serving as a stark testament to the arduous path still awaiting traversing to achieve genuine equality and comprehensive inclusivity.

Like a divine tapestry woven with threads of Christian conviction, the American Revolution fused religious fervor with revolutionary fervor. Those who dared to dream of independence saw their struggle as a holy crusade, their righteous cause etched in the fabric of freedom and bestowed by a higher power. In this turbulent era, influential spiritual leaders emerged as catalysts, their sermons and writings igniting the flames of inspiration within the colonists' hearts. The Reverend Jonathan Mayhew and the Reverend John Witherspoon stood at the forefront, casting their theological weight to unite and encourage the masses. Through this harmonious union of religious devotion and the unyielding fire of Revolution, the colonists stood resolute, fortified by a faith that knew no bounds.

The American Revolution turned the whole damn thing on its head, shaking those rigid gender roles to their core and carving out some space for the ladies in early American society. Sure, they were mainly told to sit down and shut up regarding politics and warfare. These women weren't having any of that. Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and Deborah Sampson, to name a few, weren't afraid to get their hands dirty. They took up the pen, poured their hearts out in political writings, and raised their voices in advocacy, and some of them even slapped on a pair of pants and went to war disguised as men. These gutsy moves opened the floodgates for future generations of women, sparking some fiery debates about their rights and where they belonged in this crazy society of ours.

Ah, the wondrous positives bestowed upon the land of the free! In the grand theater of history, the American Revolution, that valiant uprising against British dominion, bequeathed unto the newborn nation the coveted mantle of independence. Thus, a land untethered from the yoke of tyranny emerged, its revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and self-governance seared into the very fabric of its being. These audacious principles, birthed upon the birth of a nation, transcended the boundaries of time and space, encouraging subsequent democratic endeavors across the globe. From the blood-soaked streets of Paris during the French Revolution to the emotional struggles for emancipation from colonial oppression, the flame of inspiration ignited by the American Revolution continues to illuminate the path toward freedom and equality for all who dare to challenge the status quo.

For all its grand promises, the Revolution tragically fell short in eradicating exclusions and inequalities that plagued marginalized communities like Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women. Liberty's battle cry rang hollow as the despicable institution of slavery persisted, overshadowing the lofty ideals championed during those turbulent times. America, stained by the horror of slavery, would endure a protracted and contentious fight before finally breaking free from its clutches.

The study of the American Revolution today is vital if we aim to grasp the intricate historical mechanisms that molded the inception of the United States. Delving into this pivotal era allows us to scrutinize the formidable yearning for independence, the inherent disparities and imbalances lurking within the very fabric of the Declaration of Independence, the pervasive religious undertones that permeated the Revolution, and the revolutionary impact of women's engagement. By meticulously scrutinizing both the triumphs and the flaws of this momentous event, we glean valuable insights into the intricate complexities and inherent contradictions that defined the Revolution, consequently compelling us to introspectively grapple with the persistent obstacles of establishing a comprehensive and egalitarian society.

THE RUNDOWN

- The American Revolution was a journey toward liberation driven by a desire for independence.

- Resolutions like the Virginia Resolves and the Massachusetts Circular Letter united the colonies in opposing British policies.

- The Declaration of Independence symbolized colonial unity but excluded certain groups like Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women.

- The Revolution intertwined religious fervor with the fight for independence, with influential spiritual leaders playing a crucial role.

- Women challenged traditional gender roles during the Revolution, advocating for their rights and even participating in warfare.

- The Revolution brought independence to the developing nation, inspiring future democratic movements worldwide.

- However, it failed to eradicate exclusions and inequalities, particularly the persistence of slavery.

- Studying the American Revolution helps us understand the desire for independence, the flaws in the Declaration of Independence, the influence of religion, and the impact on women.

- By examining the Revolution's triumphs and flaws, we gain insights into the complexities of establishing an inclusive society.

QUESTIONS

- How did the resolutions such as the Virginia Resolves of 1765 and the Massachusetts Circular Letter of 1768 contribute to the unity and collective spirit among the colonies during the American Revolution?

- Discuss the paradox presented in the Declaration of Independence, which emphasizes ideals of liberty while disregarding certain groups such as Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women. What impact did these exclusions have on the revolutionary aspirations?

- In what ways did religious fervor intersect with revolutionary fervor during the American Revolution? How did influential spiritual leaders contribute to the colonists' struggle for independence?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

In a wild, electrifying episode titled "The Shot Heard Around The World," the BBC series "Rebels and Redcoats" plunges headfirst into the turbulent early stages of the American Revolutionary War. Brace yourself, for this gripping tale, revolves around the very spark that set ablaze a nation—the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Gripped by tensions and grievances that could make a rabid badger look like a friendly housecat, the American colonists and the British government find themselves on a collision course that will echo through the annals of history.

Picture this: a smoldering backdrop of political and economic unrest in the 18th-century American colonies. The stage is set as "Rebels and Redcoats," which masterfully dissects the discontent among the colonists. From the Boston Tea Party uproar to the sheer audacity of the British Parliament's Intolerable Acts, a litany of events ignites a powder keg of hostility. The episode reaches its crescendo with a blow-by-blow account of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, where the very first shots of this legendary war reverberate through time, etching their mark upon the tapestry of the American experience.

In a wild, electrifying episode titled "The Shot Heard Around The World," the BBC series "Rebels and Redcoats" plunges headfirst into the turbulent early stages of the American Revolutionary War. Brace yourself, for this gripping tale, revolves around the very spark that set ablaze a nation—the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Gripped by tensions and grievances that could make a rabid badger look like a friendly housecat, the American colonists and the British government find themselves on a collision course that will echo through the annals of history.

Picture this: a smoldering backdrop of political and economic unrest in the 18th-century American colonies. The stage is set as "Rebels and Redcoats," which masterfully dissects the discontent among the colonists. From the Boston Tea Party uproar to the sheer audacity of the British Parliament's Intolerable Acts, a litany of events ignites a powder keg of hostility. The episode reaches its crescendo with a blow-by-blow account of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, where the very first shots of this legendary war reverberate through time, etching their mark upon the tapestry of the American experience.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- Smallpox

- Women in the Revolution

- The Physical Toll

- Latinos in the American Revolution

- African Americans in the Revolution

- Jews in the Revolution

- Muslims and the Revolution

- Sex and the Revolution

- The Fourth of July

- The Declaration of Independence

- Francis Marion

- Colonial Hygiene

- Baron Friedrich von Stuben

- Gadsden Flag

- Yankee Doodle

- Miscellaneous Stories of the Rebellion

- Fallout from the American Revolution

- The Founding Fathers

- Gouverneur Morris

- Treaty of Six Nations

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity: Revolutionary War Town Hall Meeting

Objective: Engage students in a role-playing activity simulating a Revolutionary War town hall meeting, where they can express their opinions, discuss key issues, and experience the dynamics of public discourse during that period.

Instructions:

Pre-Activity Preparation:

Setting the Stage:

Role-Playing Activity:

Conclude the town hall meeting after an appropriate amount of time, ensuring that all key perspectives have been shared and discussed. Engage the students in a reflection and discussion session. Ask questions such as:

Activity: Film Analysis - "The Patriot" (2000)

Objective: To critically analyze the historical accuracy and depiction of events in the film "The Patriot" and explore its portrayal of the Revolutionary War era.

Instructions:

Pre-screening Discussion:

Film Screening:

Post-screening Discussion and Analysis:

Facilitate a class discussion about the film, encouraging students to share their initial reactions and impressions.

Explore the accuracy of the film's portrayal of historical events and characters. Prompt students with questions such as:

Reflection and Discussion:

Lead a final class discussion to encourage reflection and critical thinking about the film's impact on popular understanding of the Revolutionary War era.

Prompt students to consider the influence of cinematic storytelling on their perception of history and the importance of critically examining historical films.

By engaging students in a film analysis activity, they can explore the complexities of historical representation and develop critical thinking skills while deepening their understanding of the Revolutionary War period.

Activity: Revolutionary War Town Hall Meeting

Objective: Engage students in a role-playing activity simulating a Revolutionary War town hall meeting, where they can express their opinions, discuss key issues, and experience the dynamics of public discourse during that period.

Instructions:

Pre-Activity Preparation:

- Introduce the concept of a town hall meeting and its significance in colonial America.

- Provide students with information packets or resources covering the Revolutionary War era, ensuring they have a basic understanding of the key events, figures, and issues.

- Prepare role cards representing different characters and distribute them randomly to each student. Ensure that there is a diverse representation of perspectives.

Setting the Stage:

- Create a classroom setup resembling a town hall meeting. Arrange desks or chairs in a semi-circle to encourage face-to-face interaction and dialogue.

- Introduce the scenario: The year is 1776, and the town hall meeting is taking place in a colonial town in America. Explain the historical context, emphasizing the tensions, grievances, and aspirations of the colonists.

Role-Playing Activity:

- Give students time to review their role cards and prepare for the meeting. Encourage them to research their assigned character's perspective, beliefs, and motivations.

- Start the town hall meeting by introducing yourself as the moderator and explaining the rules of the discussion. Emphasize respectful and constructive dialogue.

- Open the floor for each character to express their viewpoints, concerns, and aspirations related to the Revolutionary War. Encourage students to speak in character, using historical knowledge and empathetic understanding.

- Facilitate the discussion by asking questions, promoting active listening, and encouraging students to respond to one another's arguments and ideas.

- Allow students to freely engage in debate, negotiations, and the exchange of ideas, just as individuals would have during a real town hall meeting.

- Encourage students to use historical evidence, primary sources, or logical reasoning to support their arguments and rebut counterarguments.

- As the moderator, ensure that the discussion remains respectful, fair, and inclusive, giving all characters an opportunity to participate.

Conclude the town hall meeting after an appropriate amount of time, ensuring that all key perspectives have been shared and discussed. Engage the students in a reflection and discussion session. Ask questions such as:

- How did it feel to step into the shoes of a Revolutionary War-era character?

- What were some of the challenges faced during the town hall meeting?

- Did your opinions or understanding of the Revolutionary War change as a result of this activity? Why or why not?

- How do you think town hall meetings influenced the development of American democracy?

- What lessons can we learn from this role-playing activity in terms of understanding historical events and different perspectives?

Activity: Film Analysis - "The Patriot" (2000)

Objective: To critically analyze the historical accuracy and depiction of events in the film "The Patriot" and explore its portrayal of the Revolutionary War era.

Instructions:

Pre-screening Discussion:

- Engage the students in a brief discussion about historical films and their role in shaping popular understanding of historical events.

- Introduce the film "The Patriot" and provide some background information about its plot, setting, and characters.

- Encourage students to share their expectations and prior knowledge of the Revolutionary War era.

Film Screening:

- Screen the film "The Patriot" in its entirety or select specific scenes that are relevant to the historical period being studied.

- Ensure that students have a way to take notes during the screening, focusing on key events, characters, and their portrayal.

Post-screening Discussion and Analysis:

Facilitate a class discussion about the film, encouraging students to share their initial reactions and impressions.

Explore the accuracy of the film's portrayal of historical events and characters. Prompt students with questions such as:

- Which events depicted in the film align with historical records, and which are fictionalized or exaggerated for cinematic purposes?

- How accurately are the major historical figures represented in the film, such as Benjamin Martin (loosely based on Francis Marion), Lord Cornwallis, or General Washington?

- Are there any instances where the film takes artistic liberties or deviates from historical facts? If so, what impact does this have on the viewer's understanding of the Revolutionary War era?

- How does the film depict the experiences of different groups of people during the war, such as soldiers, civilians, or enslaved individuals? Are these depictions historically accurate and balanced?

Reflection and Discussion:

Lead a final class discussion to encourage reflection and critical thinking about the film's impact on popular understanding of the Revolutionary War era.

Prompt students to consider the influence of cinematic storytelling on their perception of history and the importance of critically examining historical films.

By engaging students in a film analysis activity, they can explore the complexities of historical representation and develop critical thinking skills while deepening their understanding of the Revolutionary War period.

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

The American Revolution, spanning from 1775 to 1784, was like a fiery hot skillet in the kitchen of American history. It sizzled and crackled, bringing about some tasty changes to the nation. The rebel colonies had enough of being under British rule and decided to flip the script, forging their path to independence. They fought hard, united by fiery documents like the Virginia Resolves and the Massachusetts Circular Letter, sticking to the British policies they despised. The Declaration of Independence became their shining beacon, but it cast a shadow on certain folks left out of the party—Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women got dealt a lousy hand. Nevertheless, this revolution was more than just a spicy rebellion. It ignited a passionate fire for freedom and set the stage for a democratic movement that still burns bright worldwide.

History is a rich and complex dish that's often served with a side of bias. For too long, the tale of the American Revolution has been seasoned by the privileged perspectives of wealthy white Christian men. But to truly appreciate the full flavor of history, we must sample the experiences of all the groups that have contributed to the American melting pot. It's like slurping a bowl of multicultural spaghetti, each strand representing a different viewpoint and interpretation. From the struggles of Asian Americans to the stories of Latinos, from the fight for LGBTQ+ rights to the cultural significance of sports and games—it's all part of the diverse recipe that makes up America's past. So, let's grab a fork and dig into this historical feast, exploring the desire for independence, the cracks in the Declaration of Independence, the spiritual seasoning of religion, and the empowering impact on women. By embracing multiple perspectives, we can savor the complexities and ensure that the pursuit of an inclusive society remains a delicious goal.

Or, in other words:

The American Revolution, spanning from 1775 to 1784, was like a fiery hot skillet in the kitchen of American history. It sizzled and crackled, bringing about some tasty changes to the nation. The rebel colonies had enough of being under British rule and decided to flip the script, forging their path to independence. They fought hard, united by fiery documents like the Virginia Resolves and the Massachusetts Circular Letter, sticking to the British policies they despised. The Declaration of Independence became their shining beacon, but it cast a shadow on certain folks left out of the party—Native Americans, enslaved Black people, and women got dealt a lousy hand. Nevertheless, this revolution was more than just a spicy rebellion. It ignited a passionate fire for freedom and set the stage for a democratic movement that still burns bright worldwide.

History is a rich and complex dish that's often served with a side of bias. For too long, the tale of the American Revolution has been seasoned by the privileged perspectives of wealthy white Christian men. But to truly appreciate the full flavor of history, we must sample the experiences of all the groups that have contributed to the American melting pot. It's like slurping a bowl of multicultural spaghetti, each strand representing a different viewpoint and interpretation. From the struggles of Asian Americans to the stories of Latinos, from the fight for LGBTQ+ rights to the cultural significance of sports and games—it's all part of the diverse recipe that makes up America's past. So, let's grab a fork and dig into this historical feast, exploring the desire for independence, the cracks in the Declaration of Independence, the spiritual seasoning of religion, and the empowering impact on women. By embracing multiple perspectives, we can savor the complexities and ensure that the pursuit of an inclusive society remains a delicious goal.

Or, in other words:

- The American Revolution happened from 1775 to 1784.

- It made America its own country.

- The Revolution brought changes to American society, like creating a government based on democracy.

- Slavery ended in some northern states because of the Revolution.

- America's territory expanded during this time.

- Native Americans suffered because of the Revolution and were treated badly.

- Women and minorities didn't have the same rights as others in the new nation.

- The Revolution's principles of democracy, liberty, and justice are important in America today.

- It's important to learn history from different perspectives.

- History is like spaghetti with different interpretations and viewpoints.

- Studying the Revolution helps us understand how America started and the work needed for equality.

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #6

"Comedy is simply a funny way of being serious." - Peter Ustinov.

For those who do not know, Drunk History is an American educational television comedy series produced by Comedy Central. In each episode, an inebriated narrator, played by comedian and host Derek Waters, struggles to recount an event from history. At the same time, actors enact the narrator's anecdotes and lip-sync the dialogue. Watch this short video:

- Forum Discussion #6

Forum Discussion #6

"Comedy is simply a funny way of being serious." - Peter Ustinov.

For those who do not know, Drunk History is an American educational television comedy series produced by Comedy Central. In each episode, an inebriated narrator, played by comedian and host Derek Waters, struggles to recount an event from history. At the same time, actors enact the narrator's anecdotes and lip-sync the dialogue. Watch this short video:

After hearing the "oral retelling" of George Washington's Continental Army and Baron von Steuben, decipher fact and fiction. How reliable is this source? What is recorded fact? What is embellished?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

A captivating historical tale woven with humor and camaraderie follows, reminiscent of a convivial late-night conversation with Anthony Bourdain. In this heartfelt and booze-soaked encounter, the speaker expresses sincere appreciation for the warm hospitality extended their way. Amidst the lively atmosphere, their intoxicated state is laid bare with a hilarious admission: "I haven't been drunker!" The story transports us to the American Revolution, where General Von Steuben emerges as an unexpected hero. Through the lens of inebriated storytelling, we witness the dire conditions that Washington's freezing and starving troops face. Enter the irrepressible Ben Franklin, who persuades Von Steuben, an exiled Prussian war general with a penchant for Parisian parties, to join the American cause. A riotously entertaining account ensues, with Von Steuben's flamboyant arrival and subsequent transformation of the bedraggled soldiers into a formidable fighting force. As Von Steuben's undeterred spirit and Ben Walker's translation skills bridge the divide, language barriers are shrugged off with humorous anecdotes. Amidst training montages and "blah-blah-blahs," the soldiers embrace their newfound knowledge of knives and dental hygiene, their resilience bolstered by Von Steuben's unorthodox methods. The crescendo arrives in the form of decisive victories and a grateful Washington offering Von Steuben a home alongside the captivating Benjamin Walker. The legacy of Von Steuben's teachings endures, with the army following his "Blue Book" for a century, ensuring their safety and the world's salvation.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- Ferling, John E. A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Vintage Books, 1998.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800. Cornell University Press, 1996.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage Books, 1993.

LEGAL MUMBO JUMBO

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.