HST 201 Module #13

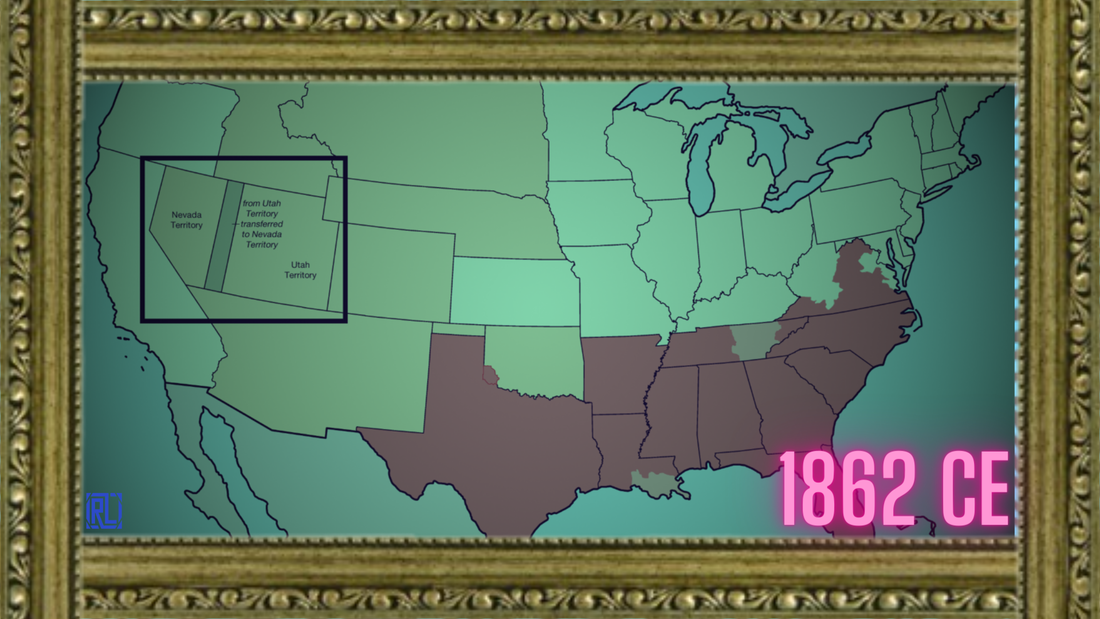

Module Thirteen: The Rest Is History (1850 CE - 1862 CE)

The period of 1850 CE to 1862 CE was a time of great change and growth in the United States. While much of the attention during this time is often focused on the looming Civil War, there were also many other significant events that shaped the country's history. It is essential to study these events today as they highlight the complexity and diversity of American history and provide context for the challenges the country still faces today.

One significant event during this time was the California Gold Rush, which began in 1848 and lasted through the 1850s. The discovery of gold in California attracted people from all over the world, including China, Europe, and South America. This influx of people led to the growth of cities and the development of infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and railways. However, it also led to significant environmental degradation and conflict with Native American tribes.

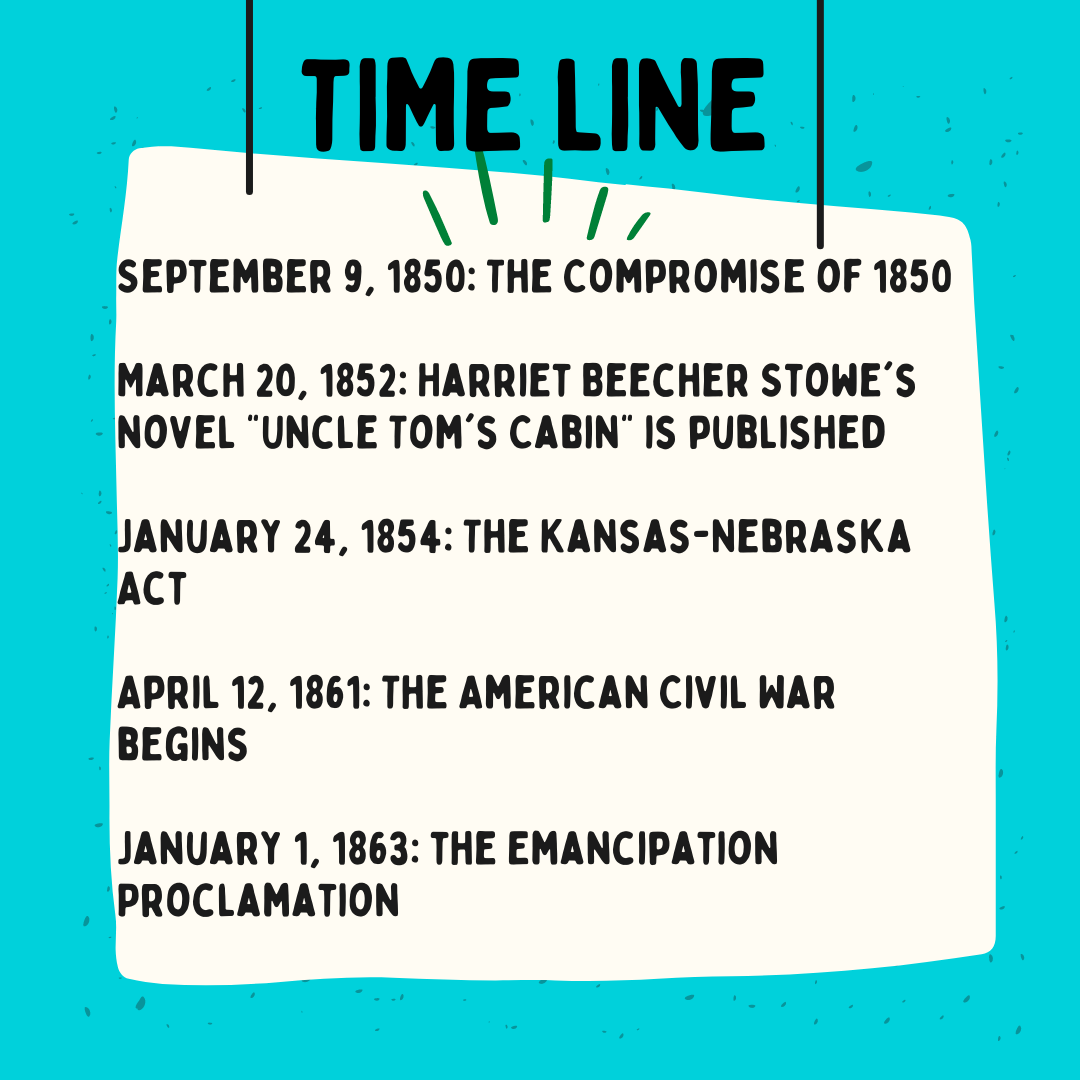

Another crucial event during this period was the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, in 1852. The book, which sold over 300,000 copies in its first year, depicted the horrors of slavery and helped to galvanize the anti-slavery movement. The novel's impact was so significant that it is often credited with helping to start the Civil War.

In addition to these events, there were also significant political and economic developments during this time. In 1850, the Compromise of 1850 was passed, which aimed to resolve the conflict between slave and free states by allowing California to enter the Union as a free state while also strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 further fueled tensions between the North and South by allowing settlers in the territories to decide whether to allow slavery. These developments ultimately led to the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, which was dedicated to stopping the expansion of slavery.

Despite the many positive developments during this period, there were also significant negatives. The growth of the country's economy and infrastructure often came at the expense of marginalized groups, including Native Americans and enslaved Africans. The conflicts that arose over land and resources during this time led to significant violence and displacement.

Studying this period of American history is essential today as it highlights the complexity and diversity of the country's past. It also provides context for the ongoing struggles for equality and justice in the United States. By understanding the successes and failures of this period, we can learn valuable lessons about how to address the challenges facing our country today.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The period of 1850 CE to 1862 CE was a time of great change and growth in the United States. While much of the attention during this time is often focused on the looming Civil War, there were also many other significant events that shaped the country's history. It is essential to study these events today as they highlight the complexity and diversity of American history and provide context for the challenges the country still faces today.

One significant event during this time was the California Gold Rush, which began in 1848 and lasted through the 1850s. The discovery of gold in California attracted people from all over the world, including China, Europe, and South America. This influx of people led to the growth of cities and the development of infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and railways. However, it also led to significant environmental degradation and conflict with Native American tribes.

Another crucial event during this period was the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, in 1852. The book, which sold over 300,000 copies in its first year, depicted the horrors of slavery and helped to galvanize the anti-slavery movement. The novel's impact was so significant that it is often credited with helping to start the Civil War.

In addition to these events, there were also significant political and economic developments during this time. In 1850, the Compromise of 1850 was passed, which aimed to resolve the conflict between slave and free states by allowing California to enter the Union as a free state while also strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 further fueled tensions between the North and South by allowing settlers in the territories to decide whether to allow slavery. These developments ultimately led to the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, which was dedicated to stopping the expansion of slavery.

Despite the many positive developments during this period, there were also significant negatives. The growth of the country's economy and infrastructure often came at the expense of marginalized groups, including Native Americans and enslaved Africans. The conflicts that arose over land and resources during this time led to significant violence and displacement.

Studying this period of American history is essential today as it highlights the complexity and diversity of the country's past. It also provides context for the ongoing struggles for equality and justice in the United States. By understanding the successes and failures of this period, we can learn valuable lessons about how to address the challenges facing our country today.

THE RUNDOWN

- The period of 1850-1862 in the US was a time of significant change and growth.

- Besides the Civil War, there were other crucial events, such as the California Gold Rush and the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

- The California Gold Rush led to the growth of cities and infrastructure but also caused environmental degradation and conflicts with Native American tribes.

- Uncle Tom's Cabin helped to galvanize the anti-slavery movement and is credited with starting the Civil War.

- Political and economic developments during this time included the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and the formation of the Republican Party in 1854.

- Marginalized groups, including Native Americans and enslaved Africans, often suffered as a result of the country's growth and development.

- Studying this period of American history is crucial today as it highlights the complexity and diversity of the country's past and provides context for ongoing struggles for equality and justice.

QUESTIONS

- What were the major political and economic developments during this period, and how did they contribute to the tensions between North and South?

- In what ways did the growth of the United States during this period come at the expense of marginalized groups, and how does this impact the ongoing struggles for justice and equality today?

- How does studying this period of American history provide valuable context for understanding the challenges facing the country today, including issues related to race, immigration, and economic inequality?

#13: History Can Be Exceptional, But Not Virtuous

The concept of exceptionalism in history is a matter of semantics, not virtue. While history can be exceptional in being different from the norm, it cannot be virtuous. American exceptionalism is the idea that the United States is unique in its values, political system, and historical development, implying that it is entitled to play a positive role on the world stage. However, this entitlement needs to be revised. The origins of American exceptionalism can be traced back to the American Revolution when the US emerged as the first new nation with distinct ideas based on principles such as liberty, equality before the law, individual responsibility, republicanism, representative democracy, and laissez-faire economics. While some European practices were transmitted to America, the US abolished them during the American Revolution, further confirming its liberalism. This liberalism laid the foundation for American exceptionalism, closely tied to republicanism, believing that sovereignty belonged to the people, not a hereditary ruling class.

The problem with exceptionalism is the assumption that it entitles the US to act as a peerless interloper without questioning its moral scruples. This was seen during the George W. Bush administration. The term was abstracted from its historical context and used to describe a phenomenon where specific political interests viewed the US as "above" or an "exception" to the law, particularly the law of nations. However, history shows that American exceptionalism is morally flawed due to issues such as slavery, civil rights, and social welfare. Even events like the revelations of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison and the government's incompetence after Hurricane Katrina opened fissures in the myth of exceptionalism. While the US has been remarkably democratic, politically stable, and free of war on its soil compared to most European countries, there have been significant exceptions, such as the American Civil War. Even after the abolition of slavery, the US government ignored the requirements of the Equal Protection Clause concerning African-Americans during the Jim Crow era and women's suffrage until the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1920. The US has also sometimes supported the overthrow of democratically elected governments to pursue other objectives, typically economic and anti-communist.

My dear friends, history is a tapestry woven with the threads of triumph and tragedy, nobility and immortality. We are often enchanted by its tales of human progress and creativity, and rightly so. But let us not forget that history also holds the darkest deeds, the most heinous acts. History can be extraordinary but far from virtuous. To prove my point, I shall delve into the annals of time and highlight certain historical events that exemplify my argument.

Let's start by setting the stage for what we mean by "exceptional" and "virtuous." Exceptional is like a shiny penny in a pile of dirt. It stands out and catches your eye. It's noteworthy, outstanding, or uncommon. It's like a tiger that's a great hunter but also a ruthless killer. Virtuous, on the other hand, is like a beacon of light in the dark. It's actions or behavior that are morally righteous, ethical, or just. When we say that history can be exceptional but not virtuous, we're saying that some events or individuals can be unique regarding their impact, significance, or influence, but that doesn't necessarily mean their actions were virtuous or morally upright. Exceptional? Yes. Virtuous? Not so much.

They said the sun never set on the British Empire for a good reason. Picture this: the British Empire, a behemoth that spanned continents and ruled over countless subjects, was a force to be reckoned with. It was a time of innovation, scientific discovery, and technological advancement. But behind the veneer of greatness and exceptionalism lay a darker truth. The British Empire was built on the backs of the oppressed and the exploited, the blood and sweat of the indigenous peoples who were conquered and subjugated. The British Empire's legacy is colonization, slavery, and racism.

The British Empire brought about significant advancements that changed the course of history. It spread the English language and culture to the far corners of the earth, and its contributions to science, technology, and medicine cannot be understated. But these exceptional achievements came at a high cost that cannot be ignored. The rise of the British Empire is a testament to the duality of human nature. It is a story of greatness, moral ambiguity, exceptionalism, and exploitation. The British Empire may have been exceptional, but it was not virtuous. Its legacy is a reminder that progress must not come at the expense of others and that the ends do not always justify the means.

So, why bother delving into history's more dubious deeds? Because, my friend, it's essential. Sure, it's important to celebrate the heroes and heroines of yore, those paragons of virtue who inspired us all to be better people. But what about the ones who weren't so virtuous? The ones who did some pretty messed up stuff? It turns out that studying those moments of unusual but questionable behavior can help us understand the complexity and nuance of human history. We can learn from the successes and failures of our ancestors and see how their actions have shaped the world we live in today. It's like being a time traveler; instead of a TARDIS or DeLorean, we've got textbooks and archives.

By digging into history, we can better understand the forces that have shaped our societies and cultures. We can start to see the patterns and cycles of human behavior and even recognize the danger of repeating past mistakes. As the great philosopher George Santayana once said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." And trust me, my friend, we don't want to go down that road again. History is not any virtuous tale of righteousness and goodness. It's a wild ride, full of ups and downs, and even the exceptional moments can be tainted by some serious dirt. Take Qin Shi Huang and the British Empire, for example. Sure, they had moments of greatness, but they left a trail of destruction and oppression in their wake.

But don't get me wrong. We have to celebrate exceptional moments in history. They show us what humans can do when we put our minds to it. However, we can't ignore the dark side of history. We have to learn from it. We must understand that history isn't just a simple tale of heroes and villains. It's a complicated mess of human experiences and actions. So, let's study history with a critical eye. Let's be nuanced in our understanding of the past. Let's recognize that history is messy and complicated, and that's okay. We have to learn from past mistakes so we don't repeat them in the future. Luckily, our history is still being written. The path we take next does not need to lead to bloodshed or heartbreak. It can be a road to continued growth and prosperity and not at the expense of others.

THE RUNDOWN

THE STATE OF THE UNION

The concept of exceptionalism in history is a matter of semantics, not virtue. While history can be exceptional in being different from the norm, it cannot be virtuous. American exceptionalism is the idea that the United States is unique in its values, political system, and historical development, implying that it is entitled to play a positive role on the world stage. However, this entitlement needs to be revised. The origins of American exceptionalism can be traced back to the American Revolution when the US emerged as the first new nation with distinct ideas based on principles such as liberty, equality before the law, individual responsibility, republicanism, representative democracy, and laissez-faire economics. While some European practices were transmitted to America, the US abolished them during the American Revolution, further confirming its liberalism. This liberalism laid the foundation for American exceptionalism, closely tied to republicanism, believing that sovereignty belonged to the people, not a hereditary ruling class.

The problem with exceptionalism is the assumption that it entitles the US to act as a peerless interloper without questioning its moral scruples. This was seen during the George W. Bush administration. The term was abstracted from its historical context and used to describe a phenomenon where specific political interests viewed the US as "above" or an "exception" to the law, particularly the law of nations. However, history shows that American exceptionalism is morally flawed due to issues such as slavery, civil rights, and social welfare. Even events like the revelations of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison and the government's incompetence after Hurricane Katrina opened fissures in the myth of exceptionalism. While the US has been remarkably democratic, politically stable, and free of war on its soil compared to most European countries, there have been significant exceptions, such as the American Civil War. Even after the abolition of slavery, the US government ignored the requirements of the Equal Protection Clause concerning African-Americans during the Jim Crow era and women's suffrage until the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1920. The US has also sometimes supported the overthrow of democratically elected governments to pursue other objectives, typically economic and anti-communist.

My dear friends, history is a tapestry woven with the threads of triumph and tragedy, nobility and immortality. We are often enchanted by its tales of human progress and creativity, and rightly so. But let us not forget that history also holds the darkest deeds, the most heinous acts. History can be extraordinary but far from virtuous. To prove my point, I shall delve into the annals of time and highlight certain historical events that exemplify my argument.

Let's start by setting the stage for what we mean by "exceptional" and "virtuous." Exceptional is like a shiny penny in a pile of dirt. It stands out and catches your eye. It's noteworthy, outstanding, or uncommon. It's like a tiger that's a great hunter but also a ruthless killer. Virtuous, on the other hand, is like a beacon of light in the dark. It's actions or behavior that are morally righteous, ethical, or just. When we say that history can be exceptional but not virtuous, we're saying that some events or individuals can be unique regarding their impact, significance, or influence, but that doesn't necessarily mean their actions were virtuous or morally upright. Exceptional? Yes. Virtuous? Not so much.

They said the sun never set on the British Empire for a good reason. Picture this: the British Empire, a behemoth that spanned continents and ruled over countless subjects, was a force to be reckoned with. It was a time of innovation, scientific discovery, and technological advancement. But behind the veneer of greatness and exceptionalism lay a darker truth. The British Empire was built on the backs of the oppressed and the exploited, the blood and sweat of the indigenous peoples who were conquered and subjugated. The British Empire's legacy is colonization, slavery, and racism.

The British Empire brought about significant advancements that changed the course of history. It spread the English language and culture to the far corners of the earth, and its contributions to science, technology, and medicine cannot be understated. But these exceptional achievements came at a high cost that cannot be ignored. The rise of the British Empire is a testament to the duality of human nature. It is a story of greatness, moral ambiguity, exceptionalism, and exploitation. The British Empire may have been exceptional, but it was not virtuous. Its legacy is a reminder that progress must not come at the expense of others and that the ends do not always justify the means.

So, why bother delving into history's more dubious deeds? Because, my friend, it's essential. Sure, it's important to celebrate the heroes and heroines of yore, those paragons of virtue who inspired us all to be better people. But what about the ones who weren't so virtuous? The ones who did some pretty messed up stuff? It turns out that studying those moments of unusual but questionable behavior can help us understand the complexity and nuance of human history. We can learn from the successes and failures of our ancestors and see how their actions have shaped the world we live in today. It's like being a time traveler; instead of a TARDIS or DeLorean, we've got textbooks and archives.

By digging into history, we can better understand the forces that have shaped our societies and cultures. We can start to see the patterns and cycles of human behavior and even recognize the danger of repeating past mistakes. As the great philosopher George Santayana once said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." And trust me, my friend, we don't want to go down that road again. History is not any virtuous tale of righteousness and goodness. It's a wild ride, full of ups and downs, and even the exceptional moments can be tainted by some serious dirt. Take Qin Shi Huang and the British Empire, for example. Sure, they had moments of greatness, but they left a trail of destruction and oppression in their wake.

But don't get me wrong. We have to celebrate exceptional moments in history. They show us what humans can do when we put our minds to it. However, we can't ignore the dark side of history. We have to learn from it. We must understand that history isn't just a simple tale of heroes and villains. It's a complicated mess of human experiences and actions. So, let's study history with a critical eye. Let's be nuanced in our understanding of the past. Let's recognize that history is messy and complicated, and that's okay. We have to learn from past mistakes so we don't repeat them in the future. Luckily, our history is still being written. The path we take next does not need to lead to bloodshed or heartbreak. It can be a road to continued growth and prosperity and not at the expense of others.

THE RUNDOWN

- American exceptionalism means the United States is unique in its beliefs, laws, and history. But it could be better.

- This idea started during the American Revolution when the US became the first new nation with its ideas.

- The problem with exceptionalism is that people might think they can do whatever they want without being moral.

- The US has had problems in the past, like slavery and unequal rights, that show the idea of exceptionalism is flawed.

- Some parts of history are important but only sometimes good. Just because something is unique or powerful doesn't mean it's morally right.

- The British Empire is an example of this - it had greatness and did some good, but it also did terrible things and took advantage of others.

- Looking at the moments in history when people acted strangely or badly can help us learn from our mistakes and understand why things are the way they are today.

THE STATE OF THE UNION

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

READING

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 1.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. First, we've got Carnes - this guy's a real maverick when it comes to studying the good ol' US of A. He's all about the secret societies that helped shape our culture in the 1800s. You know, the ones that operated behind closed doors had their fingers in all sorts of pies. Carnes is the man who can unravel those mysteries and give us a glimpse into the underbelly of American culture. We've also got Garraty in the mix. This guy's no slouch either - he's known for taking a big-picture view of American history and bringing it to life with his engaging writing style. Whether profiling famous figures from our past or digging deep into a particular aspect of our nation's history, Garraty always keeps it accurate and accessible. You don't need a Ph.D. to understand what he's saying, and that's why he's a true heavyweight in the field.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

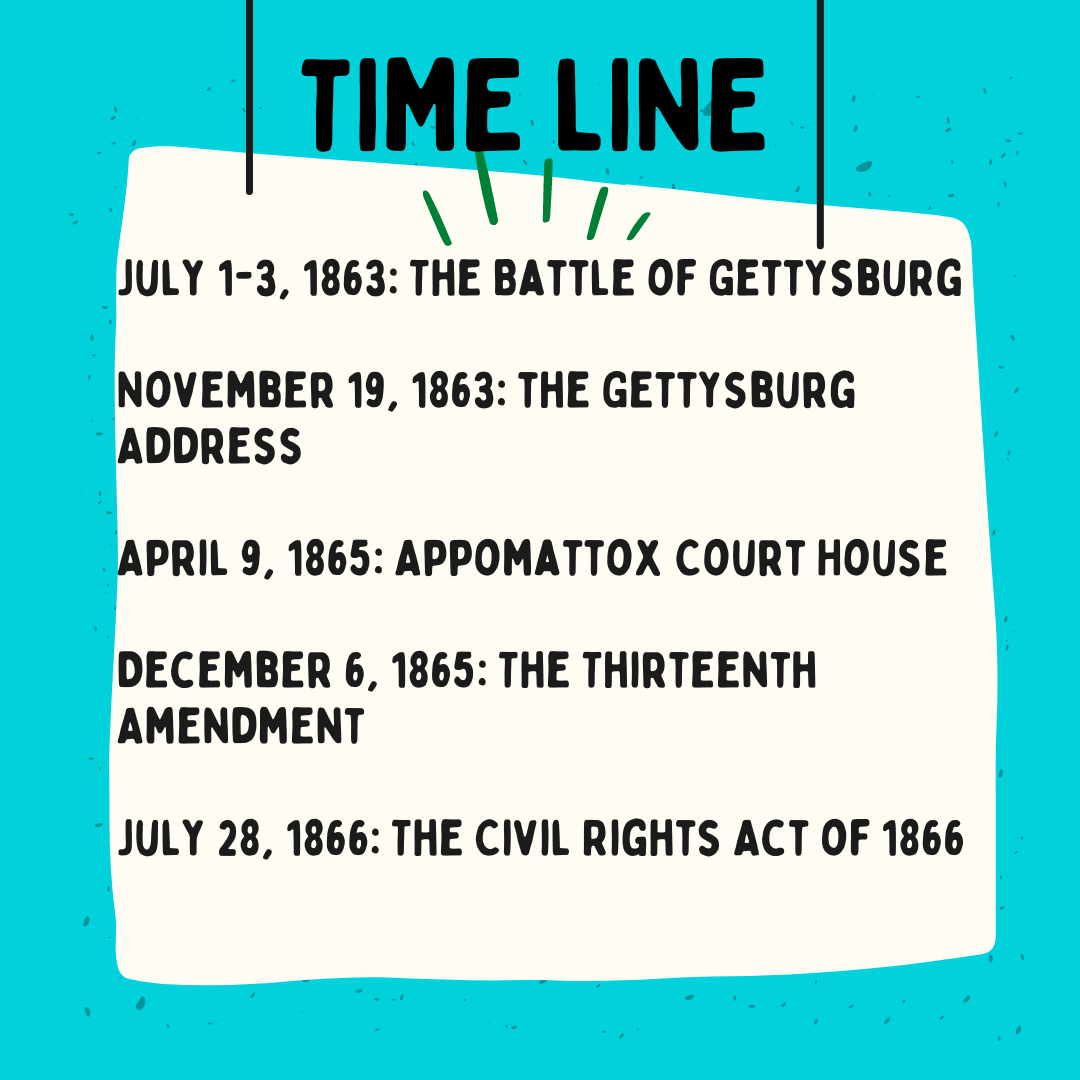

'Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... Thus, when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued January 1, 1863, it declared slaves free in those areas still fighting against the Union (which it listed very carefully), and said nothing about slaves behind Union lines. As Hofstadter put it, the Emancipation Proclamation 'had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.' The London Spectator wrote concisely: 'The principle is not that a human being cannot justly own another, hut that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States.'

Limited as it was, the Emancipation Proclamation spurred antislavery forces. By the summer of 1864, 400,000 signatures asking legislation to end slavery had been gathered and sent to Congress, something unprecedented in the history of the country. That April, the Senate had adopted the Thirteenth Amendment, declaring an end to slavery, and in January 1865, the House of Representatives followed.

With the Proclamation, the Union army was open to blacks. And the more blacks entered the war, the more it appeared a war for their liberation. The more whites had to sacrifice, the more resentment there was, particularly among poor whites in the North, who were drafted by a law that allowed the rich to buy their way out of the draft for $300. And so the draftriots of 1863 took place, uprisings of angry whites in northern cities, their targets not the rich, far away, but the blacks, near at hand. It was an orgy of death and violence. A black man in Detroit described what he saw: a mob, with kegs of beer on wagons, armed with clubs and bricks, marching through the city, attacking black men, women, children. He heard one man say: 'If we are got to he killed up for Negroes then we will kill every one in this town.'

The Civil War was one of the bloodiest in human history up to that time: 600,000 dead on both sides, in a population of 30 million-the equivalent, in the United States of 1978, with a population of 250 million, of 5 million dead. As the battles became more intense, as the bodies piled up, as war fatigue grew, the existence of blacks in the South, 4 million of them, became more and more a hindrance to the South, and more and more an opportunity for the North..."

"... Thus, when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued January 1, 1863, it declared slaves free in those areas still fighting against the Union (which it listed very carefully), and said nothing about slaves behind Union lines. As Hofstadter put it, the Emancipation Proclamation 'had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.' The London Spectator wrote concisely: 'The principle is not that a human being cannot justly own another, hut that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States.'

Limited as it was, the Emancipation Proclamation spurred antislavery forces. By the summer of 1864, 400,000 signatures asking legislation to end slavery had been gathered and sent to Congress, something unprecedented in the history of the country. That April, the Senate had adopted the Thirteenth Amendment, declaring an end to slavery, and in January 1865, the House of Representatives followed.

With the Proclamation, the Union army was open to blacks. And the more blacks entered the war, the more it appeared a war for their liberation. The more whites had to sacrifice, the more resentment there was, particularly among poor whites in the North, who were drafted by a law that allowed the rich to buy their way out of the draft for $300. And so the draftriots of 1863 took place, uprisings of angry whites in northern cities, their targets not the rich, far away, but the blacks, near at hand. It was an orgy of death and violence. A black man in Detroit described what he saw: a mob, with kegs of beer on wagons, armed with clubs and bricks, marching through the city, attacking black men, women, children. He heard one man say: 'If we are got to he killed up for Negroes then we will kill every one in this town.'

The Civil War was one of the bloodiest in human history up to that time: 600,000 dead on both sides, in a population of 30 million-the equivalent, in the United States of 1978, with a population of 250 million, of 5 million dead. As the battles became more intense, as the bodies piled up, as war fatigue grew, the existence of blacks in the South, 4 million of them, became more and more a hindrance to the South, and more and more an opportunity for the North..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... If anyone doubted the relative importance of slavery versus states’ rights in the Confederacy, the new constitution made matters plain: 'Our new Government is founded…upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man. That slavery—subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.' CSA Vice President Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia called slavery 'the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization.' In contradiction to libertarian references to 'states’ rights and liberty' made by many modern neo-Confederates, the Rebel leadership made clear its view that not only were blacks not people, but that ultimately all blacks--

including then-free Negroes—should be enslaved. In his response to the Emancipation Proclamation, Jefferson Davis stated, 'On and after Febrary 22, 1863, all free negroes within the limits of the Southern Confederacy shall be placed on slave status, and be deemed to be chattels, they and their issue forever.' Not only blacks 'within the limits' of the Confederacy, but 'all negroes who shall be taken in any of the States in which slavery does not now exist, in the progress of our arms, shall be adjudged to…occupy the slave status…[and ] all free negroes shall, ipso facto, be reduced to the condition of helotism, so that…the white and black races may be ultimately placed on a permanent basis. ' That basis, Davis said after the war started, was as 'an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere...'”

"... If anyone doubted the relative importance of slavery versus states’ rights in the Confederacy, the new constitution made matters plain: 'Our new Government is founded…upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man. That slavery—subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.' CSA Vice President Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia called slavery 'the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization.' In contradiction to libertarian references to 'states’ rights and liberty' made by many modern neo-Confederates, the Rebel leadership made clear its view that not only were blacks not people, but that ultimately all blacks--

including then-free Negroes—should be enslaved. In his response to the Emancipation Proclamation, Jefferson Davis stated, 'On and after Febrary 22, 1863, all free negroes within the limits of the Southern Confederacy shall be placed on slave status, and be deemed to be chattels, they and their issue forever.' Not only blacks 'within the limits' of the Confederacy, but 'all negroes who shall be taken in any of the States in which slavery does not now exist, in the progress of our arms, shall be adjudged to…occupy the slave status…[and ] all free negroes shall, ipso facto, be reduced to the condition of helotism, so that…the white and black races may be ultimately placed on a permanent basis. ' That basis, Davis said after the war started, was as 'an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere...'”

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"... To DuBois, slavery kept African Americans out of the culture of repression that whites had created, and because of this, slaves created a uniquely liberated culture that valued pleasure over work and freedom over conformity. DuBois argued that there were some ex-slaves who behaved like John Freeman. But many did not, and to DuBois, the culture of the slaves that was let loose by emancipation

was a gift to America and the world. In fact, during Reconstruction many ex-slaves fled the fields for cities, where they found horns and formed 'jubilee' bands. Many discovered pianos and invented a music called ragtime that set millions of white feet dancing. And others picked up guitars and began to play music we call the blues. Out of that alchemy emerged a gift to all those who hated work, loved pleasure, and yearned to be as free as a child. The great tragedy of Reconstruction, according to DuBois, was that so many whites turned down the gift, 'sneered' at black culture and mocked it, and chose to consider it inferior. But DuBois, like most historians today, nonetheless wished that the ex-slaves had been made into full American citizens. What he did not understand was that John Freeman and all the ex-slaves who chose citizenship turned down the gift as well. If Reconstruction had been fully realized, many of the freedoms and joys given to us by the slaves would have been taken away. If the freedmen had been made into citizens, there would be no jazz..."

"... To DuBois, slavery kept African Americans out of the culture of repression that whites had created, and because of this, slaves created a uniquely liberated culture that valued pleasure over work and freedom over conformity. DuBois argued that there were some ex-slaves who behaved like John Freeman. But many did not, and to DuBois, the culture of the slaves that was let loose by emancipation

was a gift to America and the world. In fact, during Reconstruction many ex-slaves fled the fields for cities, where they found horns and formed 'jubilee' bands. Many discovered pianos and invented a music called ragtime that set millions of white feet dancing. And others picked up guitars and began to play music we call the blues. Out of that alchemy emerged a gift to all those who hated work, loved pleasure, and yearned to be as free as a child. The great tragedy of Reconstruction, according to DuBois, was that so many whites turned down the gift, 'sneered' at black culture and mocked it, and chose to consider it inferior. But DuBois, like most historians today, nonetheless wished that the ex-slaves had been made into full American citizens. What he did not understand was that John Freeman and all the ex-slaves who chose citizenship turned down the gift as well. If Reconstruction had been fully realized, many of the freedoms and joys given to us by the slaves would have been taken away. If the freedmen had been made into citizens, there would be no jazz..."

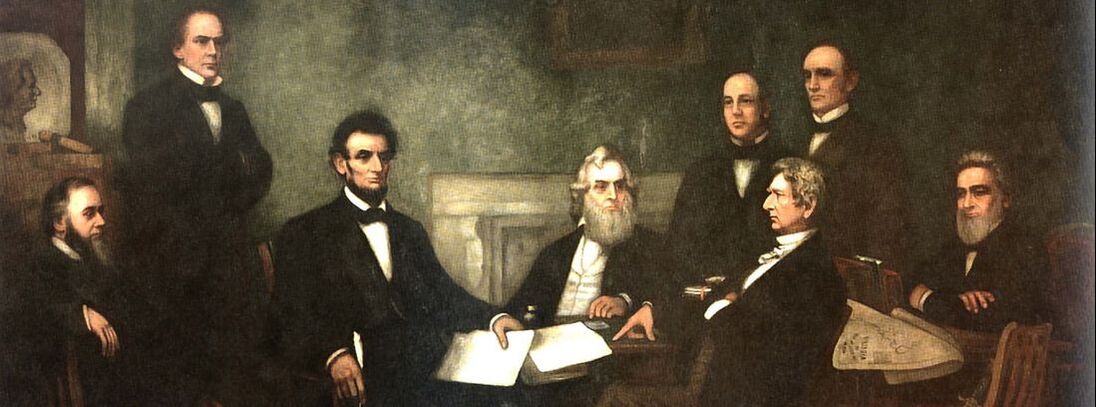

Now, let's not get carried away here. The Emancipation Proclamation, a document dropped by President Abraham Lincoln like a hot mixtape during the Civil War, was a big deal in American history, shining a light on the tangled web of race, power, and cultural defiance. While it was bold in the battle against slavery, its effect on ending the whole "owning humans" gig during the war was tepid. And if that wasn't enough, those Confederate folks were all we're good with enslaving people while simultaneously giving African American culture the cold shoulder during Reconstruction. We're diving deep into the limited impact of that fancy Proclamation on slavery, unpacking the Confederate leadership's love affair with human bondage, and shaking our heads at the straight-up rejection of African American culture during Reconstruction.

January 1, 1863, will always be remembered as the day when the Emancipation Proclamation was unleashed upon the world, proclaiming the freedom of all enslaved individuals in Confederate territory. But let's not get ahead of ourselves with grandiose visions of instantaneous liberation, for this historical document had a few hitches. Picture this: you're an enslaved person, eagerly anticipating the sweet taste of freedom, only to realize that if you happen to be located in a Union-held border state or an area already captured by the Union, you're out of luck. Sorry, Charlie, the Proclamation isn't coming for you. Honest Abe's decree was limited to those areas where the Confederacy still clung to power, with the Union's influence being about as minimal as the chances of finding a decent Wi-Fi signal in the 19th century. Did I mention that the Proclamation's effectiveness depended on the Union military winning battles and heading into Confederate territory? You had to wait for the boys in blue to march in and plant their flags before Uncle Sam would even consider setting you free. Now, before you get all righteous about the Emancipation Proclamation, let's be clear: it didn't abolish slavery. It was more like a strategic maneuver to put a wrench in the Confederacy's economic gears by messing with their labor force. Lincoln played three-dimensional chess while the Confederacy was stuck in a perpetual game of checkers. So, while the Proclamation may not have been the total liberation many had hoped for, it was a clever move in the game of war, leaving the Confederacy to ponder how a single document could have such a disruptive impact on their grand plans.

In the twisted tango of the Civil War, the Confederate brass pirouetted with an unabashed devotion to slavery, illuminating the intricate interplay between race and dominance. The Southern states flaunted their true intentions like a peacock in full regalia, with the secession documents serving as their twisted script. Take South Carolina's "Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina," a manifest that dripped with the unvarnished truth: preserving slavery was their number one ticket out of the Union. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cronies clung to the notion of human bondage like a drowning man clings to a piece of driftwood. They bellowed and roared, vehemently defending the perverse institution as if it were the marrow of their existence. How they clung, their grip unyielding even as the tides turned against them. This unwavering commitment showcased the deeply entrenched racial and power dynamics that set the stage for the Southern states' grand exit and their stubborn resistance to the winds of emancipation.

Reconstruction, that fancy post-Civil War era, tried its darnedest to shake things down South. Their newfound freedoms were Met with a big old "nope" from the haters. They rejected African American culture left and right, a not-so-subtle reminder of that deep-rooted discrimination. the Ku Klux Klan came to town, armed with their restrictive laws cleverly dubbed "Black Codes." Their mission was to Squash any African American political, economic, and social progress. The lengths some folks will go to maintain their precious racial hierarchies. Denied civil rights, segregated to the nines, and smacked with racially motivated violence, those poor souls were trapped in a hostile environment and in a never-ending cycle of systemic racism.

Delving into the Emancipation Proclamation's feeble impact, the Confederate bigwigs' unwavering devotion to slavery, and the cold-shouldering of African American culture during Reconstruction holds profound significance for several reasons. It unravels the intricate tapestry of race, power, and cultural defiance that weaves throughout American history, enlightening us on the enduring shadows of slavery and racial injustice that persist in our society's fabric. By immersing ourselves in these tumultuous chapters, we unearth invaluable insights into the progress made since the Civil War and Reconstruction, unmasking the unyielding hurdles plaguing marginalized communities today. This historical sagacity nourishes empathy, tolerance, and inclusivity, for it casts a searing light upon the tribulations endured by African Americans and other marginalized groups, propelling us toward the noble pursuit of a future that brims with justice and equity.

Though proclaimed with great intent, the Emancipation Proclamation revealed its limitations in curbing the shackles of slavery during the tumultuous era of the Civil War. Meanwhile, the Confederate leadership's staunch dedication to the abhorrent institution and their outright rejection of African American culture during the fraught period of Reconstruction elucidate the complex tapestry of race, power, and cultural defiance woven throughout American history. These gripping chapters unfold with invaluable lessons, granting us a profound comprehension of the trials endured by African Americans and the indelible imprints of slavery and racial inequity that persist today. So let us delve into the depths of our collective story, for within lies the wisdom to forge an inclusive and equitable future where the echoes of the past enlighten our path forward.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

January 1, 1863, will always be remembered as the day when the Emancipation Proclamation was unleashed upon the world, proclaiming the freedom of all enslaved individuals in Confederate territory. But let's not get ahead of ourselves with grandiose visions of instantaneous liberation, for this historical document had a few hitches. Picture this: you're an enslaved person, eagerly anticipating the sweet taste of freedom, only to realize that if you happen to be located in a Union-held border state or an area already captured by the Union, you're out of luck. Sorry, Charlie, the Proclamation isn't coming for you. Honest Abe's decree was limited to those areas where the Confederacy still clung to power, with the Union's influence being about as minimal as the chances of finding a decent Wi-Fi signal in the 19th century. Did I mention that the Proclamation's effectiveness depended on the Union military winning battles and heading into Confederate territory? You had to wait for the boys in blue to march in and plant their flags before Uncle Sam would even consider setting you free. Now, before you get all righteous about the Emancipation Proclamation, let's be clear: it didn't abolish slavery. It was more like a strategic maneuver to put a wrench in the Confederacy's economic gears by messing with their labor force. Lincoln played three-dimensional chess while the Confederacy was stuck in a perpetual game of checkers. So, while the Proclamation may not have been the total liberation many had hoped for, it was a clever move in the game of war, leaving the Confederacy to ponder how a single document could have such a disruptive impact on their grand plans.

In the twisted tango of the Civil War, the Confederate brass pirouetted with an unabashed devotion to slavery, illuminating the intricate interplay between race and dominance. The Southern states flaunted their true intentions like a peacock in full regalia, with the secession documents serving as their twisted script. Take South Carolina's "Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina," a manifest that dripped with the unvarnished truth: preserving slavery was their number one ticket out of the Union. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cronies clung to the notion of human bondage like a drowning man clings to a piece of driftwood. They bellowed and roared, vehemently defending the perverse institution as if it were the marrow of their existence. How they clung, their grip unyielding even as the tides turned against them. This unwavering commitment showcased the deeply entrenched racial and power dynamics that set the stage for the Southern states' grand exit and their stubborn resistance to the winds of emancipation.

Reconstruction, that fancy post-Civil War era, tried its darnedest to shake things down South. Their newfound freedoms were Met with a big old "nope" from the haters. They rejected African American culture left and right, a not-so-subtle reminder of that deep-rooted discrimination. the Ku Klux Klan came to town, armed with their restrictive laws cleverly dubbed "Black Codes." Their mission was to Squash any African American political, economic, and social progress. The lengths some folks will go to maintain their precious racial hierarchies. Denied civil rights, segregated to the nines, and smacked with racially motivated violence, those poor souls were trapped in a hostile environment and in a never-ending cycle of systemic racism.

Delving into the Emancipation Proclamation's feeble impact, the Confederate bigwigs' unwavering devotion to slavery, and the cold-shouldering of African American culture during Reconstruction holds profound significance for several reasons. It unravels the intricate tapestry of race, power, and cultural defiance that weaves throughout American history, enlightening us on the enduring shadows of slavery and racial injustice that persist in our society's fabric. By immersing ourselves in these tumultuous chapters, we unearth invaluable insights into the progress made since the Civil War and Reconstruction, unmasking the unyielding hurdles plaguing marginalized communities today. This historical sagacity nourishes empathy, tolerance, and inclusivity, for it casts a searing light upon the tribulations endured by African Americans and other marginalized groups, propelling us toward the noble pursuit of a future that brims with justice and equity.

Though proclaimed with great intent, the Emancipation Proclamation revealed its limitations in curbing the shackles of slavery during the tumultuous era of the Civil War. Meanwhile, the Confederate leadership's staunch dedication to the abhorrent institution and their outright rejection of African American culture during the fraught period of Reconstruction elucidate the complex tapestry of race, power, and cultural defiance woven throughout American history. These gripping chapters unfold with invaluable lessons, granting us a profound comprehension of the trials endured by African Americans and the indelible imprints of slavery and racial inequity that persist today. So let us delve into the depths of our collective story, for within lies the wisdom to forge an inclusive and equitable future where the echoes of the past enlighten our path forward.

THE RUNDOWN

- The Emancipation Proclamation was a document President Abraham Lincoln released during the Civil War.

- It aimed to free enslaved individuals in Confederate territory but had limitations.

- The Proclamation did not apply to Union-held border states or areas already captured by the Union.

- Its effectiveness depended on the Union military winning battles and entering Confederate territory.

- The Proclamation was a strategic move to disrupt the Confederacy's economy by interfering with their labor force.

- It did not abolish slavery entirely but played a clever role in the war.

- The Confederate leaders were intensely devoted to slavery and defended it despite facing defeat.

- Reconstruction after the Civil War tried to bring change, but African American culture was rejected.

- The Ku Klux Klan and "Black Codes" restricted African American progress and maintained racial hierarchies.

- African Americans faced discrimination, segregation, and violence during Reconstruction.

- Understanding the limited impact of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Confederate leaders' devotion to slavery, and the rejection of African American culture during Reconstruction provides insights into the ongoing challenges faced by marginalized communities today.

- Studying this history promotes empathy, tolerance, and inclusivity and helps us work toward a more just and equitable future.

QUESTIONS

- In what ways was the Emancipation Proclamation a strategic maneuver rather than a complete abolition of slavery? How did it disrupt the Confederacy's plans and impact their economy?

- How did the secession documents and the Confederate leadership's devotion to slavery expose the Southern states' deep-rooted racial and power dynamics during the Civil War? In what ways did they resist the forces of emancipation?

- What were some of the significant challenges faced by African Americans during the Reconstruction era? How did the rejection of African American culture, the implementation of "Black Codes," and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan hinder progress and perpetuate systemic racism?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

In the tempestuous American Civil War, Atlanta was seething with germination only Sherman could sow. As a pivotal Confederate hub of manufacturing and strategic significance, this city stood at the center of President Lincoln's re-election ambitions. Meanwhile, enslaved African Americans clung to Sherman like he was the Chosen One, their last, best hope for liberation. The battle scenes unfolded with Sherman's meticulous planning and relentless resolve; his veterans, like a pack of underdogs gone wild, thwarted every desperate move by General Hood. After five weeks of relentless bombardment, they transformed Atlanta into a post-apocalyptic wasteland, finally prompting Hood's retreat and one spectacular boom that must have shattered every eardrum within a hundred miles. While the North erupted in joyous celebration, Sherman decided to play the villain, evicting all civilians—including those secret Yankees who had cunningly concealed their true loyalties—because, well, who needs babysitting when you're in the business of war? Torn apart yet triumphant, Atlanta was a chilling reminder that victory is often just a fancy name for destruction.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- Sherman's March to the Sea

- Ironclads

- Piracy Part Four

- Andersonville Prison

- Emancipation Proclamation

- Gettysburg Address

- Appomattox Courthouse

- Battle of Palmito Ranch

- The 13th Amendment

- Photojournalism

- The Aftermath of War

- Pinkertons

- The Camel Corps

- The King of Beaver Island

- The Pony Express

- California Police Tax

- Cochise

- 1860s Fashion

- Ex Parte Merryman

- The Homestead Act

- Sioux Uprising

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Assignment: Artistic Expression in the Mid-19th Century

Objective: To explore and engage with the art and literature of the mid-19th century, while allowing students to express their creativity through their own artistic work inspired by the themes and ideas of the time period.

Research Phase:

Exploration and Reflection:

Artistic Expression:

Creative Process:

Presentation and Reflection:

Note: Encourage students to embrace their creativity and express their unique perspectives through their artistic projects. Assess the assignments based on their understanding of the themes and ideas of the mid-19th century, as well as the quality and creativity of their artistic expression.

Assignment: Mock Constitutional Convention

Objective: To engage students in an interactive and immersive learning experience, where they assume the roles of delegates from different states during a mock constitutional convention. This activity aims to deepen their understanding of the issues surrounding slavery, representation, and federalism during the mid-19th century in the United States. Students will actively participate in debates, negotiations, and the drafting of constitutional amendments or resolutions, replicating the challenges faced by historical figures of the time.

Instructions:

Role Assignment:

Preparing for the Convention:

Convention Simulation:

Conclusion:

Assignment: Artistic Expression in the Mid-19th Century

Objective: To explore and engage with the art and literature of the mid-19th century, while allowing students to express their creativity through their own artistic work inspired by the themes and ideas of the time period.

Research Phase:

- Begin by introducing students to the art and literature of the mid-19th century. Provide examples and discuss the works of Hudson River School painters, such as Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church.

- Introduce students to the poetry of Walt Whitman, focusing on his collection "Leaves of Grass," and discuss its themes and style.

- Introduce students to the novels of Harriet Beecher Stowe, particularly "Uncle Tom's Cabin," and discuss its impact on the time period.

Exploration and Reflection:

- Organize a class discussion to explore the common themes, ideas, and artistic techniques present in the works of the Hudson River School painters, Walt Whitman's poetry, and Harriet Beecher Stowe's novels.

- Encourage students to analyze the historical context and social issues addressed in the works. Discuss how art and literature can serve as a reflection of society and a catalyst for change.

Artistic Expression:

- Explain to students that they will now have the opportunity to create their own artistic work inspired by the mid-19th century. They can choose to express themselves through painting, poetry, or prose.

- Provide them with a list of themes and ideas commonly found in the works of the Hudson River School painters, Walt Whitman's poetry, and Harriet Beecher Stowe's novels. Examples include nature, the American landscape, individualism, social justice, slavery, or the pursuit of freedom.

- Encourage students to conduct additional research and gather inspiration from the works of the artists and writers studied.

Creative Process:

- Set aside dedicated class time for students to work on their artistic projects. Provide art supplies, writing materials, and resources like laptops or tablets, as needed.

- Encourage students to experiment with different artistic techniques, styles, and mediums to bring their ideas to life. Provide guidance and feedback as they work on their projects.

Presentation and Reflection:

- Allocate a day for students to present their artistic creations to the class. Each student should explain their creative choices and how their work connects to the themes and ideas of the mid-19th century.

- After each presentation, facilitate a discussion where classmates can ask questions, provide feedback, and reflect on the connections between the original works studied and the students' artistic interpretations.

- Conclude the activity with a reflection session where students share their experiences, insights, and any newfound appreciation for the art and literature of the mid-19th century.

Note: Encourage students to embrace their creativity and express their unique perspectives through their artistic projects. Assess the assignments based on their understanding of the themes and ideas of the mid-19th century, as well as the quality and creativity of their artistic expression.

Assignment: Mock Constitutional Convention

Objective: To engage students in an interactive and immersive learning experience, where they assume the roles of delegates from different states during a mock constitutional convention. This activity aims to deepen their understanding of the issues surrounding slavery, representation, and federalism during the mid-19th century in the United States. Students will actively participate in debates, negotiations, and the drafting of constitutional amendments or resolutions, replicating the challenges faced by historical figures of the time.

Instructions:

- Divide the class into groups, assigning each group a different state to represent during the mock constitutional convention. Ensure that there is a diverse representation of states from various regions of the country.

- Provide students with background information about the historical context, key issues, and major stakeholders of the period (1850 CE - 1862 CE) in relation to slavery, representation, and federalism.

- Familiarize students with the United States Constitution and its amendments, particularly the relevant sections and provisions related to the assigned topics.

Role Assignment:

- Assign each student within the group a specific role as a delegate from their respective state. Students should research and become familiar with the historical figures they are representing. Some roles could include senators, representatives, governors, or prominent political figures of the time.

- Encourage students to study the views, opinions, and perspectives of their assigned historical figures, considering their state's interests, economic factors, and political considerations.

Preparing for the Convention:

- Instruct students to conduct thorough research on the issues of slavery, representation, and federalism during the assigned time period. They should examine the historical debates, prominent speeches, and key events that shaped these issues.

- Provide students with primary sources, such as speeches, letters, newspaper articles, or legal documents, to gain insight into the arguments and viewpoints of the time. Secondary sources like books, articles, and documentaries can also be utilized for a comprehensive understanding.

- Encourage students to take notes, analyze the perspectives of their assigned historical figures, and identify potential areas of compromise or contention.

Convention Simulation:

- Conduct the mock constitutional convention in a structured and organized manner, providing a platform for students to express their assigned roles' views and engage in debates.

- Allocate specific time for each state to present their concerns, proposals, and arguments related to slavery, representation, and federalism. Encourage students to use historical evidence, logical reasoning, and persuasive rhetoric to support their positions.

- Facilitate respectful and constructive discussions among the delegates, promoting active listening, critical thinking, and open-mindedness.

- Encourage students to negotiate, propose compromises, and draft constitutional amendments or resolutions that address the concerns and interests of various states.

Conclusion:

- Once the debates and negotiations have concluded, allow students to reflect on the process and outcomes of the mock constitutional convention. Discuss the challenges faced by the historical delegates and how their decisions influenced the course of US history during that period.

- Facilitate a class discussion to compare and contrast the different perspectives, compromises, and resolutions proposed by the student delegates.

- Emphasize the significance of understanding the historical context and the complexities of the issues discussed, highlighting the lasting impact of decisions made during that era.

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

From 1850 to 1862, America was a hotbed of change and growth, all happening in the shadow of the Civil War. This period saw the rise of remarkable events like the California Gold Rush and the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The Gold Rush transformed cities and built up the infrastructure, but damn, it also brought environmental destruction and clashed with Native American tribes. On the flip side, Uncle Tom's Cabin sparked a fire in the hearts of those fighting against slavery, and some say it even set the stage for the Civil War. Political and economic shifts, such as the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the birth of the Republican Party, left their marks on this era. But let's not forget that amid all this progress, marginalized folks like Native Americans and enslaved Africans often got the short end of the stick. Studying this period uncovers the intricacies of America's past, shedding light on the ongoing struggle for equality and justice.

American exceptionalism, my friends, is an idea that the good ol' US of A is unique in its beliefs, laws, and history. But here's the thing: it's not all sunshine and rainbows. This notion sprouted during the American Revolution when the nation stood proud as the first with its revolutionary ideas. However, exceptionalism can be a slippery slope, making folks think they can do whatever they want without any moral compass. Let's face it, America has had its fair share of problems: slavery, unequal rights—the very foundation of exceptionalism crumbles under the weight of these sins. Just because something is special or mighty doesn't mean it's automatically righteous, my friends. Take a gander at the history of the British Empire, for instance. Sure, They had moments of grandeur, but they also left behind a trail of terrible deeds and exploitation. To truly understand our present, we must reckon with our past and examine those moments when people acted strangely or downright bad. Through this introspection, we learn from our mistakes and gain insight into the world we live in today.

Or, in other words:

From 1850 to 1862, America was a hotbed of change and growth, all happening in the shadow of the Civil War. This period saw the rise of remarkable events like the California Gold Rush and the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The Gold Rush transformed cities and built up the infrastructure, but damn, it also brought environmental destruction and clashed with Native American tribes. On the flip side, Uncle Tom's Cabin sparked a fire in the hearts of those fighting against slavery, and some say it even set the stage for the Civil War. Political and economic shifts, such as the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the birth of the Republican Party, left their marks on this era. But let's not forget that amid all this progress, marginalized folks like Native Americans and enslaved Africans often got the short end of the stick. Studying this period uncovers the intricacies of America's past, shedding light on the ongoing struggle for equality and justice.

American exceptionalism, my friends, is an idea that the good ol' US of A is unique in its beliefs, laws, and history. But here's the thing: it's not all sunshine and rainbows. This notion sprouted during the American Revolution when the nation stood proud as the first with its revolutionary ideas. However, exceptionalism can be a slippery slope, making folks think they can do whatever they want without any moral compass. Let's face it, America has had its fair share of problems: slavery, unequal rights—the very foundation of exceptionalism crumbles under the weight of these sins. Just because something is special or mighty doesn't mean it's automatically righteous, my friends. Take a gander at the history of the British Empire, for instance. Sure, They had moments of grandeur, but they also left behind a trail of terrible deeds and exploitation. To truly understand our present, we must reckon with our past and examine those moments when people acted strangely or downright bad. Through this introspection, we learn from our mistakes and gain insight into the world we live in today.

Or, in other words:

- From 1850 to 1862, the United States greatly changed and grew bigger.

- The California Gold Rush made cities grow but harmed the environment and caused fights with Native American tribes.

- Uncle Tom's Cabin book helped the fight against slavery and led to the Civil War.

- Important political and economic events happened, like the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

- Native Americans and enslaved Africans suffered during this time.

- Studying this period to understand America's history and the ongoing struggle for fairness and justice is important.

- American exceptionalism means the United States thinks it's special and better than others.

- It started during the American Revolution when America had its new ideas.

- But it's flawed because America had problems like slavery and unequal rights.

- Just because something is unique or powerful doesn't mean it's good or right.

- We should learn from history and the bad things people did to make things better today.

- Understanding the limited impact of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Confederate leaders' support of slavery, and the rejection of African American culture during Reconstruction can help us understand the challenges marginalized groups face now.

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #14

The Washington Post YouTube channel provides comprehensive news coverage and insightful analysis on various topics, keeping viewers well-informed and engaged.

The "Lost Cause of the Confederacy," also known as the "Lost Cause," refers to an ideology in American history that distorts the truth and aims to negate past realities. This ideology asserts that despite the Confederate States losing the American Civil War, their cause was noble and admirable. It promotes the supposed merits of the pre-war Southern society. It portrays the conflict as a predominantly defensive struggle for the Southern way of life or "states' rights" against significant "northern aggression." Concurrently, the Lost Cause downplays or outright denies the crucial role that slavery played in sparking the war. Do some research and please answer the following questions:

- Forum Discussion #14

Forum Discussion #14

The Washington Post YouTube channel provides comprehensive news coverage and insightful analysis on various topics, keeping viewers well-informed and engaged.

The "Lost Cause of the Confederacy," also known as the "Lost Cause," refers to an ideology in American history that distorts the truth and aims to negate past realities. This ideology asserts that despite the Confederate States losing the American Civil War, their cause was noble and admirable. It promotes the supposed merits of the pre-war Southern society. It portrays the conflict as a predominantly defensive struggle for the Southern way of life or "states' rights" against significant "northern aggression." Concurrently, the Lost Cause downplays or outright denies the crucial role that slavery played in sparking the war. Do some research and please answer the following questions:

From pulling the information from what you have learned about in class, why is the “Lost Cause” a folly way of thinking? Why do many still hold onto the notion of a noble war fought against “northern aggression?”

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Once upon a time, Richmond fell, and Abraham Lincoln visited the city, saying, "Let 'em up easy," when asked how to treat the defeated Confederates. Richmond was the Confederate capital, adorned with monuments to their war heroes, which is rare for a war's losing side. The way the Civil War ended was as rare as a talking unicorn. There's a clash about what the war was about, with some folks saying it was about states' rights, but the historical record sets the record straight—it was about slavery, plain and simple. Yet, we can't deny that racism ran rampant back then, even among those fighting for the Union. Lincoln wasn't an immediate champion of equal rights for Black folks, but he made some strides later on. The whole Lost Cause business arose, a bunch of propaganda to make the Confederacy look like they were fighting for a just cause and lost because they were outnumbered. The ladies played a big role in creating memorials and shrines for the fallen Confederates, conveniently leaving out the stories of the Black soldiers who fought as bravely. The Lost Cause even infiltrated popular culture, with films and textbooks perpetuating its falsehoods. But there's hope for enlightenment, as efforts are being made to provide a more accurate understanding of history. Knowing the truth is important because believing lies can lead to disrespect and a generational loss of dignity. Richmond is waking up to its truth and reconciliation, striving for a more equitable future.

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Once upon a time, Richmond fell, and Abraham Lincoln visited the city, saying, "Let 'em up easy," when asked how to treat the defeated Confederates. Richmond was the Confederate capital, adorned with monuments to their war heroes, which is rare for a war's losing side. The way the Civil War ended was as rare as a talking unicorn. There's a clash about what the war was about, with some folks saying it was about states' rights, but the historical record sets the record straight—it was about slavery, plain and simple. Yet, we can't deny that racism ran rampant back then, even among those fighting for the Union. Lincoln wasn't an immediate champion of equal rights for Black folks, but he made some strides later on. The whole Lost Cause business arose, a bunch of propaganda to make the Confederacy look like they were fighting for a just cause and lost because they were outnumbered. The ladies played a big role in creating memorials and shrines for the fallen Confederates, conveniently leaving out the stories of the Black soldiers who fought as bravely. The Lost Cause even infiltrated popular culture, with films and textbooks perpetuating its falsehoods. But there's hope for enlightenment, as efforts are being made to provide a more accurate understanding of history. Knowing the truth is important because believing lies can lead to disrespect and a generational loss of dignity. Richmond is waking up to its truth and reconciliation, striving for a more equitable future.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty!: An American History. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story. Encounter Books, 2019.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Oakes, James. Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012.

- Rothman, Joshua D. Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom's Cabin. Dover Publications, 1991.

- "Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina." Avalon Project, Yale Law School. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp

LEGAL MUMBO JUMBO

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.