HST 202 Module #05

Flappers and Fortunes Lost (1920 CE - 1928 CE)

The 1920s were a fascinating blend of advancement and bias, affluence and adversity, all intertwined with the melodies of jazz and the allure of flapper fashion. It's as if America hosted a gathering and left common sense off the guest list. Imagine the aftermath of the Great War, a nation emerging from turmoil to the tune of bathtub gin and the rhythmic pulse of jazz. Economic prosperity abounds, with the stock market soaring like a Gatsby soirée. Yet, amidst the champagne showers, there are those submerged in the torrents of inequality.

And then arrives the Ku Klux Klan, resurfacing from the depths of prejudice like a recurring nightmare. They bring with them the arsenal of hate: racism, xenophobia, and attire reminiscent of a bargain bin Halloween costume. It's as though progress took a stumble, thrusting the nation backward into darker times. But it wasn't all bleak. There were champions of progress, battling ignorance like valiant warriors. W.E.B. Du Bois and Jane Addams fought against the tide of inequality while the masses were preoccupied with mastering the Charleston.

Consider the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, a glaring example of a miscarriage of justice. These Italian anarchists found themselves caught amid waves of fear and paranoia, akin to innocent bystanders in a gangland shootout. Despite fervent protests, they met their end on the gallows. Justice seemed to have lost its way, wandering into the shadows of injustice. So, what's the lesson here? Aside from history's penchant for irony, it's a reminder that progress is not a linear path. It's more akin to a stumbling journey through a dimly lit alley with wrong turns and colorful characters. Though the Roaring Twenties may be a chapter of the past, its resonance still echoes in our society today.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

The 1920s were a fascinating blend of advancement and bias, affluence and adversity, all intertwined with the melodies of jazz and the allure of flapper fashion. It's as if America hosted a gathering and left common sense off the guest list. Imagine the aftermath of the Great War, a nation emerging from turmoil to the tune of bathtub gin and the rhythmic pulse of jazz. Economic prosperity abounds, with the stock market soaring like a Gatsby soirée. Yet, amidst the champagne showers, there are those submerged in the torrents of inequality.

And then arrives the Ku Klux Klan, resurfacing from the depths of prejudice like a recurring nightmare. They bring with them the arsenal of hate: racism, xenophobia, and attire reminiscent of a bargain bin Halloween costume. It's as though progress took a stumble, thrusting the nation backward into darker times. But it wasn't all bleak. There were champions of progress, battling ignorance like valiant warriors. W.E.B. Du Bois and Jane Addams fought against the tide of inequality while the masses were preoccupied with mastering the Charleston.

Consider the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, a glaring example of a miscarriage of justice. These Italian anarchists found themselves caught amid waves of fear and paranoia, akin to innocent bystanders in a gangland shootout. Despite fervent protests, they met their end on the gallows. Justice seemed to have lost its way, wandering into the shadows of injustice. So, what's the lesson here? Aside from history's penchant for irony, it's a reminder that progress is not a linear path. It's more akin to a stumbling journey through a dimly lit alley with wrong turns and colorful characters. Though the Roaring Twenties may be a chapter of the past, its resonance still echoes in our society today.

THE RUNDOWN

- Economic prosperity, cultural upheaval, and technological advances characterized the 1920s.

- Flappers, jazz, and mass media reshaped national identity. Radio, cinema, and automobiles revolutionized communication and transportation.

- Technological innovations and consumerism fueled unprecedented prosperity. Stock market soared, but income inequality widened, leaving many marginalized.

- Klan's return propagated discrimination, targeting minorities and fostering fear.

- Progressive reformers like Du Bois and Addams fought for social justice.

- The era's impact, technological advancements, and cultural shifts continue to shape today. Understanding both positive and negative aspects informs our ongoing quest for a just society.

QUESTIONS

- How did the 1920s represent both advancement and bias in American society?

- What were some of the key cultural aspects of the 1920s, such as jazz and flapper fashion, and how did they reflect the era's spirit?

- Describe the economic prosperity of the 1920s, contrasting it with the experiences of those facing inequality.

#5 History in Not Monolithic

History is woven with threads so intricate they resemble a labyrinth of spaghetti. Some perceive it as a tidy journey from Point A to Point B as if we're all dutifully following a predetermined blueprint for societal perfection. But let me assure you: that blueprint is more convoluted than a Hitchcock thriller.

Consider colonization, for instance. Europeans are traversing the seas, claiming land as if it were a frenzied Black Friday sale. They may have viewed it as manifest destiny or some other lofty concept but for the indigenous inhabitants? It felt more like an unwelcome visitor arriving unannounced, bringing along a retinue, devouring all provisions, and demanding gratitude for the meager crumbs left behind.

And the Civil Rights Movement? Sure, we've been presented with the sanitized rendition in textbooks, with MLK Jr. delivering his iconic speech and harmonious scenes of unity. But behind the curtain? It was a battlefield, with individuals risking life and limb merely to occupy the same diner stools as their white peers. Yet, here's the revelation: history transcends the prominent figures and pivotal moments. It encompasses the untold narratives—the whispers in the shadows, the scribbles in the margins. Consider the women who fiercely fought for suffrage or the enslaved souls who dared to envision liberty within a world constructed upon their toil.

History isn't a uniform garment; it's messy, intricate, and sometimes repulsively raw. Yet therein lies its allure. It serves as a mirror reflecting our entirety, flaws included.

So, let's discard the antiquated recipe books and embrace the disorder. Let's amplify the voices stifled for far too long and infuse vigor into this insipid narrative we've been force-fed. Only by acknowledging the breadth of human experience can we aspire to grasp our trajectory—where we've journeyed from and where the winding road ahead may lead us.

RUNDOWN

History is woven with threads so intricate they resemble a labyrinth of spaghetti. Some perceive it as a tidy journey from Point A to Point B as if we're all dutifully following a predetermined blueprint for societal perfection. But let me assure you: that blueprint is more convoluted than a Hitchcock thriller.

Consider colonization, for instance. Europeans are traversing the seas, claiming land as if it were a frenzied Black Friday sale. They may have viewed it as manifest destiny or some other lofty concept but for the indigenous inhabitants? It felt more like an unwelcome visitor arriving unannounced, bringing along a retinue, devouring all provisions, and demanding gratitude for the meager crumbs left behind.

And the Civil Rights Movement? Sure, we've been presented with the sanitized rendition in textbooks, with MLK Jr. delivering his iconic speech and harmonious scenes of unity. But behind the curtain? It was a battlefield, with individuals risking life and limb merely to occupy the same diner stools as their white peers. Yet, here's the revelation: history transcends the prominent figures and pivotal moments. It encompasses the untold narratives—the whispers in the shadows, the scribbles in the margins. Consider the women who fiercely fought for suffrage or the enslaved souls who dared to envision liberty within a world constructed upon their toil.

History isn't a uniform garment; it's messy, intricate, and sometimes repulsively raw. Yet therein lies its allure. It serves as a mirror reflecting our entirety, flaws included.

So, let's discard the antiquated recipe books and embrace the disorder. Let's amplify the voices stifled for far too long and infuse vigor into this insipid narrative we've been force-fed. Only by acknowledging the breadth of human experience can we aspire to grasp our trajectory—where we've journeyed from and where the winding road ahead may lead us.

RUNDOWN

- History is depicted as a complex tapestry with diverse perspectives, contrary to the oversimplified narrative often presented.

- The colonization of America is examined from European and Native American viewpoints, highlighting oppression and progress.

- The Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s is portrayed as a culmination of varied experiences, leading to legislative changes and challenging discrimination.

- Reevaluation of historical events like women's suffrage and the transatlantic slave trade enriches understanding by including marginalized perspectives.

- Neglecting violence and resistance during historical movements obscures the challenges faced and the complete picture of history.

- The conclusion emphasizes that history is dynamic, necessitating the study of various angles to learn from mistakes and foster a just society, as illustrated by examples like colonization and the Civil Rights Movement.

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- COMING SOON

READING

Carnes, Chapter 23 Woodrow Wilson and the Great War

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

Carnes, Chapter 23 Woodrow Wilson and the Great War

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. American Destiny: Narrative of a Nation. 4th ed. Vol. 2.: Pearson, 2011.

Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty are respected historians who have made notable contributions to American history. Carnes specializes in American education and culture, focusing on the role of secret societies in shaping American culture in the 19th century. Garraty is known for his general surveys of American history, his biographies of American historical figures and studies of specific aspects of American history, and his clear and accessible writing.

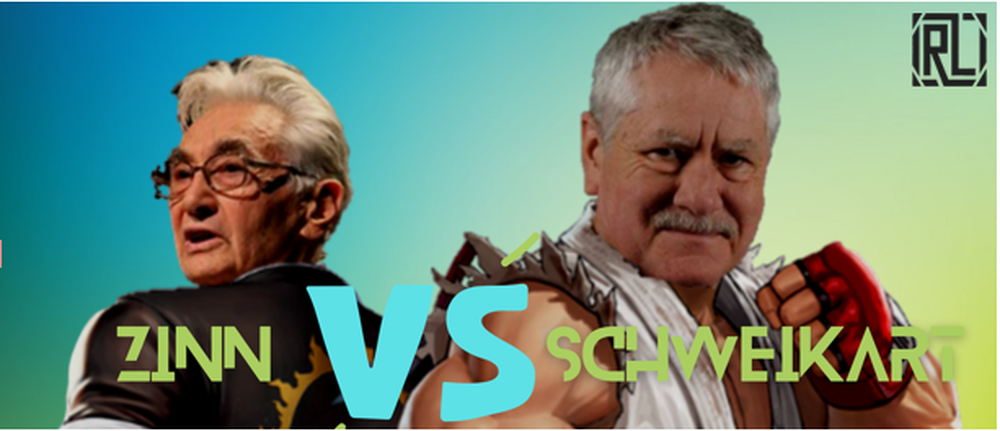

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

The Ku Klux Klan was revived in the 1920s, and it spread into the North. By 1924 it had 4M million members. The NAACP seemed helpless in the face of mob violence and race hatred everywhere. The impossibility of the black persons ever being considered equal in white

America was the theme of the nationalist movement led in the 1920s by Marcus Garvey. He preached black pride, racial separation, and a return to Africa, which to him held the only hope for black unity and survival. But Garvey's movement, inspiring as it was to some

blacks, could not make much headway against the powerful white supremacy currents of the postwar decade.

There was some truth to the standard picture of the twenties as a time of prosperity and fun the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties. Unemployment was down, from 4,270,000 in 1921 to a little over 2 million in 1927. The general level of wages for workers rose. Some farmers made a lot of money. The 40 percent of all families who made over $2,000 a year could buy new gadgets: autos, radios, refrigerators. Millions of people were not doing badly-and they could shut out of the picture the others-the tenant farmers, black and white, the immigrant families in the big cities either without work or not making enough to get the basic

necessities.

But prosperity was concentrated at the top. While from 1922 to 1929 real wages in manufacturing went up per capita 1.4 percent a year, the holders of common stocks gained 16.4 percent a year. Six million families (42 percent of the total) made less than $1,000 a year. One-tenth of 1 percent of the families at the top received as much income as 42 percent of the families at the bottom, according to a report of the Brookings Institution. Every year in the 1920s, about 25,000 workers were killed on the job and 100,000 permanently disabled. Two million people in New York City lived in tenements condemned as rattraps.

The Ku Klux Klan was revived in the 1920s, and it spread into the North. By 1924 it had 4M million members. The NAACP seemed helpless in the face of mob violence and race hatred everywhere. The impossibility of the black persons ever being considered equal in white

America was the theme of the nationalist movement led in the 1920s by Marcus Garvey. He preached black pride, racial separation, and a return to Africa, which to him held the only hope for black unity and survival. But Garvey's movement, inspiring as it was to some

blacks, could not make much headway against the powerful white supremacy currents of the postwar decade.

There was some truth to the standard picture of the twenties as a time of prosperity and fun the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties. Unemployment was down, from 4,270,000 in 1921 to a little over 2 million in 1927. The general level of wages for workers rose. Some farmers made a lot of money. The 40 percent of all families who made over $2,000 a year could buy new gadgets: autos, radios, refrigerators. Millions of people were not doing badly-and they could shut out of the picture the others-the tenant farmers, black and white, the immigrant families in the big cities either without work or not making enough to get the basic

necessities.

But prosperity was concentrated at the top. While from 1922 to 1929 real wages in manufacturing went up per capita 1.4 percent a year, the holders of common stocks gained 16.4 percent a year. Six million families (42 percent of the total) made less than $1,000 a year. One-tenth of 1 percent of the families at the top received as much income as 42 percent of the families at the bottom, according to a report of the Brookings Institution. Every year in the 1920s, about 25,000 workers were killed on the job and 100,000 permanently disabled. Two million people in New York City lived in tenements condemned as rattraps.

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"...As the idealism of Prohibition faded, and the reality of crime associated with bootlegging set in, the effort to ban alcohol began to unravel. One reason was that enforcement mechanisms were pitifully weak. The government had hired only fifteen hundred agents to support local police, compared to the thousand gunmen in Al Capone’s employ added to the dozens of other gangs of comparable size. Gunplay and violence, as law enforcement agents tried to shut down bootlegging operations, led to countless deaths. Intergang warfare killed hundreds in Chicago alone between 1920 and 1927. By some estimates, the number of bootleggers and illegal saloons went up after Prohibition. Washington, D.C., and Boston both saw the stratospheric increase in the number of liquor joints. Kansas, the origin of the dry movement, did not have a town where alcohol could not be obtained, at least according to an expert witness before the House Judiciary Committee.

The leadership of the early Prohibition movement included many famous women, such as Carry Nation, who were concerned with protecting the nuclear family from the assault by liquor and prostitution. She was wrong in her assessment of the problem. Far from protecting women by improving the character of men, Prohibition perversely led women down to the saloon. Cocktails, especially, were in vogue among these 'liberated' women, who, like their reformer sisters, came from the ranks of the well-to-do.

Liquor spread through organized crime into the hands (or bellies) of the lower classes only gradually in the 1920s, eventually entering into the political arena with the presidential campaign of Al Smith. By that time, much of the support for Prohibition had disappeared because several factors had coalesced to destroy the dry coalition. First, the drys lost some of their flexible and dynamic leaders, who in turn were replaced with more dogmatic and less imaginative types. Second, dry

politicians, who were already in power, bore much of the blame for the economic fallout associated with the market crash in 1929. Third, public tastes had shifted (literally in some cases) to accommodate the new freedom of the age represented by the automobile and the radio. Restricting individual choices about anything did not fit well with those new icons. Finally, states chafed under federal laws. Above all, the liquor industry pumped massive resources into the repeal campaign, obtaining a “monopoly on…press coverage by providing reporters with reliable—and constant— information. 'By the late 1920s and early 1930s, “it was unusual to find a story about prohibition in small local papers that did not have its origin with the [anti-Prohibition forces].'"

"...As the idealism of Prohibition faded, and the reality of crime associated with bootlegging set in, the effort to ban alcohol began to unravel. One reason was that enforcement mechanisms were pitifully weak. The government had hired only fifteen hundred agents to support local police, compared to the thousand gunmen in Al Capone’s employ added to the dozens of other gangs of comparable size. Gunplay and violence, as law enforcement agents tried to shut down bootlegging operations, led to countless deaths. Intergang warfare killed hundreds in Chicago alone between 1920 and 1927. By some estimates, the number of bootleggers and illegal saloons went up after Prohibition. Washington, D.C., and Boston both saw the stratospheric increase in the number of liquor joints. Kansas, the origin of the dry movement, did not have a town where alcohol could not be obtained, at least according to an expert witness before the House Judiciary Committee.

The leadership of the early Prohibition movement included many famous women, such as Carry Nation, who were concerned with protecting the nuclear family from the assault by liquor and prostitution. She was wrong in her assessment of the problem. Far from protecting women by improving the character of men, Prohibition perversely led women down to the saloon. Cocktails, especially, were in vogue among these 'liberated' women, who, like their reformer sisters, came from the ranks of the well-to-do.

Liquor spread through organized crime into the hands (or bellies) of the lower classes only gradually in the 1920s, eventually entering into the political arena with the presidential campaign of Al Smith. By that time, much of the support for Prohibition had disappeared because several factors had coalesced to destroy the dry coalition. First, the drys lost some of their flexible and dynamic leaders, who in turn were replaced with more dogmatic and less imaginative types. Second, dry

politicians, who were already in power, bore much of the blame for the economic fallout associated with the market crash in 1929. Third, public tastes had shifted (literally in some cases) to accommodate the new freedom of the age represented by the automobile and the radio. Restricting individual choices about anything did not fit well with those new icons. Finally, states chafed under federal laws. Above all, the liquor industry pumped massive resources into the repeal campaign, obtaining a “monopoly on…press coverage by providing reporters with reliable—and constant— information. 'By the late 1920s and early 1930s, “it was unusual to find a story about prohibition in small local papers that did not have its origin with the [anti-Prohibition forces].'"

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"...Beginning on January 16, 1920, the date the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect, rumrunners employed by Italian and Jewish crime syndicates delivered liquor all along the coasts of the Pacific, Atlantic, and the Gulf of Mexico. In the North, giant sleds carrying cases of liquor were pulled across the border from Canada. Thanks to these efforts and the overwhelming desire of Americans to drink, consumption of sacramental wine increased by eight hundred thousand gallons during the first two years of Prohibition. Speakeasies, many of which were owned by criminals, could be found in every neighborhood in every city in the country. In Manhattan alone, there were five thousand speakeasies at one point in the 1920s. Women, who had been barred from most saloons before Prohibition, were welcome in speakeasies and became regular customers. When a rumrunner boat escaped a Coast Guard ship off Coney Island one summer day, thousands of people on the beach stood and cheered. All of this helps explain why gangsters became the heroes of the Prohibition era, both in the movies and in real life..."

"...Beginning on January 16, 1920, the date the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect, rumrunners employed by Italian and Jewish crime syndicates delivered liquor all along the coasts of the Pacific, Atlantic, and the Gulf of Mexico. In the North, giant sleds carrying cases of liquor were pulled across the border from Canada. Thanks to these efforts and the overwhelming desire of Americans to drink, consumption of sacramental wine increased by eight hundred thousand gallons during the first two years of Prohibition. Speakeasies, many of which were owned by criminals, could be found in every neighborhood in every city in the country. In Manhattan alone, there were five thousand speakeasies at one point in the 1920s. Women, who had been barred from most saloons before Prohibition, were welcome in speakeasies and became regular customers. When a rumrunner boat escaped a Coast Guard ship off Coney Island one summer day, thousands of people on the beach stood and cheered. All of this helps explain why gangsters became the heroes of the Prohibition era, both in the movies and in real life..."

What Does Professor Lancaster Think?

There is an intricate waltz of American politics, where lofty ideals mingle with nefarious dealings, and the upper echelon indulges in champagne while the common folk navigate disillusionment's murky depths. Buckle up, for we're embarking on a tumultuous journey through the labyrinthine corridors of power, privilege, and sporadic glimpses of liberty. Envision colonial America, a realm of promise and prospects, where every landowner ostensibly possessed voting and office-holding rights. Ostensibly democratic, proper? Think again. Beneath the facade of egalitarianism lurked affluent plantation owners, orchestrating affairs akin to puppeteers in a twisted theater.

Consider Virginia and Maryland as prime examples of political chicanery. Yes, they boasted quaint assemblies where citizens could feign participation, yet reality painted a different picture – with tobacco magnates wielding influence like playing a rigged game of Monopoly. Fast forward to the nation's inception, where our forebearers penned the seminal documents shaping American democracy. Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness – sounds inviting. Alas, while Thomas Jefferson extolled inherent freedoms, his cohorts were busy enacting laws like the Alien and Sedition Acts, ushering in constitutional crises at breakneck speed.

Imagine being barred from criticizing the government or welcoming foreign visitors without risking treason charges. It smacks of authoritarianism masked as democracy. Welcome to America, where free expression is as scarce as political integrity. But let's not dwell excessively on the past, for contemporary politics offers its spectacle. From populist insurgencies to Twitter skirmishes among flamboyant leaders, the American political circus never fails to captivate.

So, what's the takeaway from this convoluted saga? Firstly, skepticism toward historical narratives is prudent. Behind noble aspirations often lie pools of corruption, and behind politicians' smiles lurk the guiles of peddlers. Nevertheless, I would like to remain optimistic. As long as scrutiny persists and advocacy endures, there's hope for the quagmire we call democracy. So, arm yourselves with conviction and ballots, for the curtain hasn't fallen on this drama – and given American politics, the denouement promises to be riveting.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

There is an intricate waltz of American politics, where lofty ideals mingle with nefarious dealings, and the upper echelon indulges in champagne while the common folk navigate disillusionment's murky depths. Buckle up, for we're embarking on a tumultuous journey through the labyrinthine corridors of power, privilege, and sporadic glimpses of liberty. Envision colonial America, a realm of promise and prospects, where every landowner ostensibly possessed voting and office-holding rights. Ostensibly democratic, proper? Think again. Beneath the facade of egalitarianism lurked affluent plantation owners, orchestrating affairs akin to puppeteers in a twisted theater.

Consider Virginia and Maryland as prime examples of political chicanery. Yes, they boasted quaint assemblies where citizens could feign participation, yet reality painted a different picture – with tobacco magnates wielding influence like playing a rigged game of Monopoly. Fast forward to the nation's inception, where our forebearers penned the seminal documents shaping American democracy. Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness – sounds inviting. Alas, while Thomas Jefferson extolled inherent freedoms, his cohorts were busy enacting laws like the Alien and Sedition Acts, ushering in constitutional crises at breakneck speed.

Imagine being barred from criticizing the government or welcoming foreign visitors without risking treason charges. It smacks of authoritarianism masked as democracy. Welcome to America, where free expression is as scarce as political integrity. But let's not dwell excessively on the past, for contemporary politics offers its spectacle. From populist insurgencies to Twitter skirmishes among flamboyant leaders, the American political circus never fails to captivate.

So, what's the takeaway from this convoluted saga? Firstly, skepticism toward historical narratives is prudent. Behind noble aspirations often lie pools of corruption, and behind politicians' smiles lurk the guiles of peddlers. Nevertheless, I would like to remain optimistic. As long as scrutiny persists and advocacy endures, there's hope for the quagmire we call democracy. So, arm yourselves with conviction and ballots, for the curtain hasn't fallen on this drama – and given American politics, the denouement promises to be riveting.

THE RUNDOWN

- There is is an intricate relationship between government, politics, and ordinary citizens in American history.

- It highlights skepticism towards government authority and the manipulation of lower-class grievances for political gain.

- Colonial politics showcased a blend of broad political participation and the emergence of a political elite, shaping early American governance.

- The tension between lofty founding ideals and the harsh realities of political corruption and civil rights abuses underscores the challenges faced in American governance.

- Growing discontent towards entrenched political establishments fueled demands for reform, exemplified by movements like the Populist Movement of the late 19th century.

- Studying these complexities is vital for understanding contemporary challenges and fostering informed civic engagement in shaping a more just and equitable society.

QUESTIONS

- Discuss the contrast between the lofty ideals of American democracy, as expressed in documents like the Declaration of Independence, and the reality of laws like the Alien and Sedition Acts. How do these conflicting narratives shape your understanding of American history?

- What role does free expression play in a democracy? How does the author suggest that this fundamental right was restricted in early America, and do you see parallels to contemporary issues surrounding freedom of speech?

- Reflecting on the current state of American politics, what similarities and differences do you see between the historical examples provided and modern political dynamics?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

WATCH

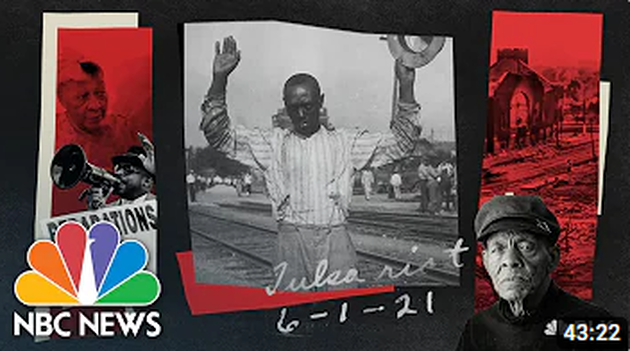

Blood on Black Wall Street: The Legacy of the Tulsa Race Massacre (2022) - 45 min.

WATCH

Blood on Black Wall Street: The Legacy of the Tulsa Race Massacre (2022) - 45 min.

THE RUNDOWN

In the aftermath of Greenwood's devastation, where the scent of prosperity once lingered in the air, now lies the haunting memory of a brutality akin to infernal depths. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 wasn't a mere blot in history; it epitomized an abhorrent chapter, exposing humanity's pretense of civility as hollow. Imagine a scorching summer day when a young black man named Dick Rowland enters an elevator, minding his own business. Then, add a white woman – an essential ingredient for any racially charged tragedy – falsely accusing him of impropriety. The tension simmers until it erupts into a riot, fueling a blaze of racial animosity that transforms Greenwood into a battlefield.

In the aftermath of Greenwood's devastation, where the scent of prosperity once lingered in the air, now lies the haunting memory of a brutality akin to infernal depths. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 wasn't a mere blot in history; it epitomized an abhorrent chapter, exposing humanity's pretense of civility as hollow. Imagine a scorching summer day when a young black man named Dick Rowland enters an elevator, minding his own business. Then, add a white woman – an essential ingredient for any racially charged tragedy – falsely accusing him of impropriety. The tension simmers until it erupts into a riot, fueling a blaze of racial animosity that transforms Greenwood into a battlefield.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEYTERMS

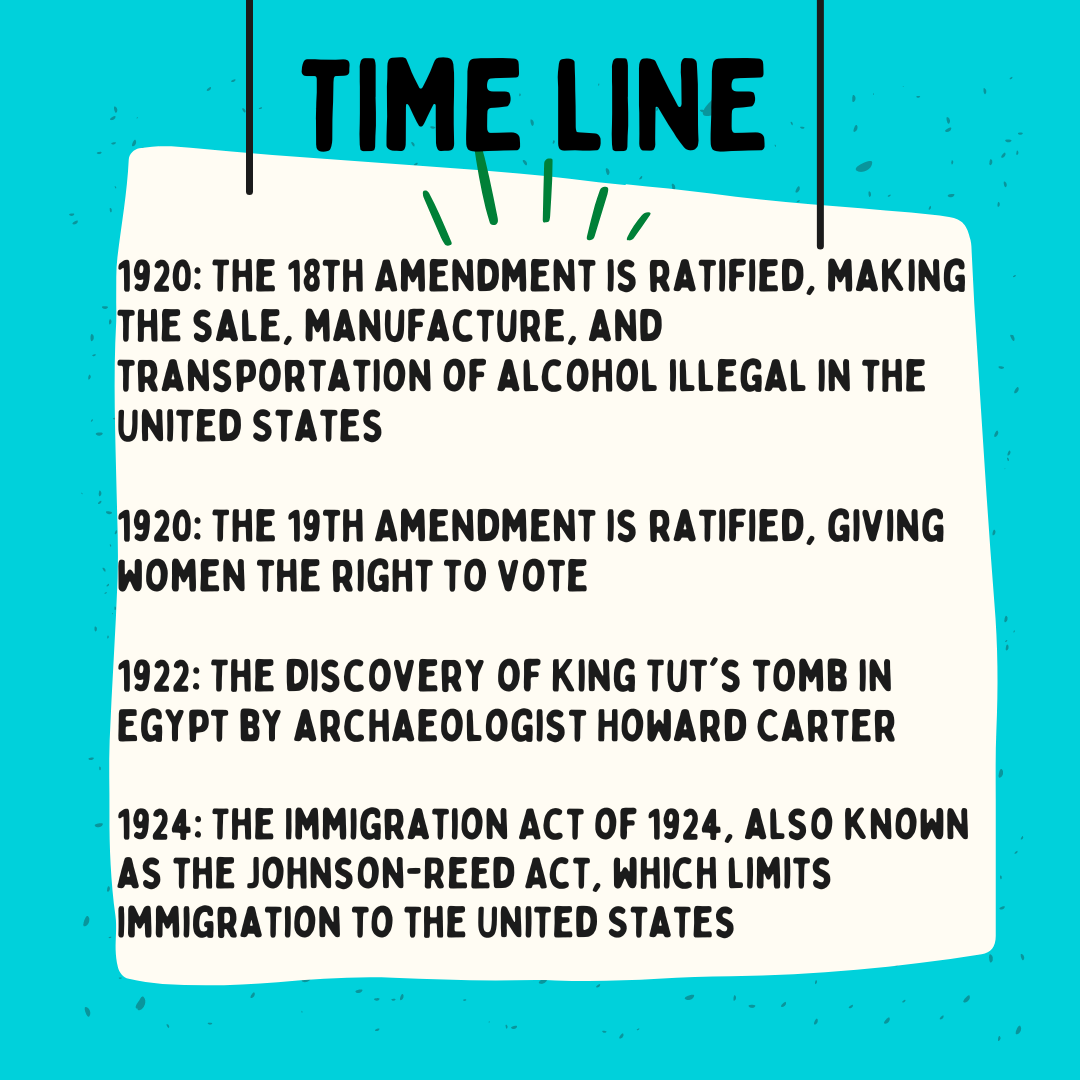

- 1920 Volstead Act

- 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain

- 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

- 1922 peanut butter/Jelly Sandwich

- 1922 Insulin

- 1922 Charles Atlas

- 1922 The Power of Love

- 1923 First Folk Blue Album

- 1924 Johnson-Reed Act

- 1924 The Society for Human Rights

- 1925- Motels

- 1925 Scopes Trial

- 1926 Cheeseburger

- 1926- Route 66

- 1926 Ernest Hemingway

- 1926 Veteran’s Day

- 1927 The Jazz Singer

- 1927 Smores

- 1928 Steamboat Willie

- 1928 The Queen's Messenger

- 1928 Bernarr Macfadden

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity #1: Jigsaw Activity

Assignment:

Research:

Activity #2: Panel Activity- "Exploring the Roaring Twenties"

Objective:

Activity #1: Jigsaw Activity

Assignment:

- You will be divided into small groups.

- Each group will focus on a specific topic related to US history between 1920 and 1928. The groups are:

- Women's Suffrage Activists: This group focuses on the women's suffrage movement and the passage of the 19th Amendment during the 1920s. They study key figures, events, and strategies of the suffrage movement.

- Prohibition Opponents: This group explores the opposition to Prohibition and the rise of speakeasies during the 1920s. They examine the prohibition era's social, cultural, and political implications.

- Harlem Renaissance Participants: This group delves into the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural and artistic movement among African Americans centered in Harlem, New York, during the 1920s. They study notable figures, works of art, and the impact of the movement on American society.

- Immigrant Communities: This group examines the experiences of immigrant communities in the United States during the 1920s, including the effects of immigration restrictions such as the National Origins Act. They explore immigrant communities' challenges, contributions, and cultural dynamics during this period.

- Red Scare Victims: This group investigates the Red Scare and the Palmer Raids, focusing on the government's response to perceived threats of communism and radicalism during the 1920s. They study the impact of anti-radical hysteria on civil liberties and political dissenters.

Research:

- Your group will become experts on your assigned topic.

- Use online resources to research and understand the key points and significance of your topic.

- Discuss and summarize the main points of your topic within your group.

- Prepare a brief presentation (around 5 minutes) to share with the class.

- After preparing your presentation, your class will be rearranged into new groups, each consisting of one member from different expert groups. These new groups are:

- Prohibition and the Rise of Speakeasies: Explore the enactment and consequences of the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. Research the emergence of illegal drinking establishments known as speakeasies and their cultural impact during the Prohibition era.

- The Harlem Renaissance: Investigate the cultural and artistic movement that took place in Harlem, New York, during the 1920s. Focus on key figures such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Duke Ellington, and their contributions to literature, music, and the arts.

- Women's Suffrage and the 19th Amendment: Examine the women's suffrage movement and the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote in 1920. Explore the strategies and leaders of the suffrage movement, including Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul.

- Immigration Restrictions and the National Origins Act: Analyze the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the National Origins Act, which restricted immigration based on national origins and established quotas. Discuss the political and social factors that led to the enactment of this legislation and its impact on immigration patterns.

- The Red Scare and Palmer Raids: Investigate the anti-communist hysteria and fear of radicalism that swept the United States after World War I. Focus on the actions of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and the raids conducted by the Department of Justice to arrest and deport suspected radicals, including anarchists and communists.

- Present your assigned topic to your new group members.

- Share the most important information and engage in discussions.

- Together with your new group, create a visual representation (e.g., timeline, chart, or infographic) that integrates the information from all the topics presented by your group members.

- Wrap up the activity by summarizing the key takeaways and discussing the importance of collaboration and understanding historical events in context.

- Follow these directions carefully to ensure successful completion of the jigsaw activity.

Activity #2: Panel Activity- "Exploring the Roaring Twenties"

Objective:

- Your task is to delve into the vibrant decade of the 1920s in the United States, known as the Roaring Twenties, by participating in a panel presentation focused on various aspects of this era.

- Panel Assignment: You will be assigned to a panel representing a specific theme or aspect of the 1920s. Examples include Prohibition, the Harlem Renaissance, Women's Rights, Economic Prosperity, Immigration, Labor Unrest, Technology, and the Jazz Age.

- Conduct thorough research on your assigned topic. Explore key events, influential figures, social movements, and cultural phenomena of the 1920s related to your panel theme. Utilize reliable sources, including textbooks, academic articles, and primary sources.

- Panel Presentation: Prepare a concise presentation (5-10 minutes) that provides an overview of your panel topic. Include important facts, significant developments, and notable individuals or movements relevant to your theme.

- Enhance your presentation with visual aids such as images, videos, music clips, or excerpts from primary sources. These can help illustrate key points and engage your audience.

- Engagement: Actively participate in your panel presentation by delivering your assigned segment effectively and contributing to the overall coherence of the discussion.

- Engage in a brief Q&A session following your presentation. Be prepared to answer questions from your classmates and facilitate a meaningful dialogue about your panel topic.

- Post-Presentation Discussion: Take part in a class-wide discussion after all panels have presented. Reflect on the interconnectedness of the different themes explored and consider the broader implications of the Roaring Twenties on American society.

- Analyze how the events, trends, and cultural shifts of the 1920s continue to influence contemporary American culture, politics, and society.

- Conclude the activity by summarizing the key insights gained from the panel presentations and emphasizing the importance of understanding historical periods in shaping our present-day world.

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

The 1920s was a decade of so roaring that even a tiger's yawn could be mistaken for a church bell's chime. Envision this: flappers fluttering, jazz aficionados improvising, and the stock market ascending to heights rivaling a pterodactyl fueled by energy drinks. It was an epoch where the aspiration of emulating Jay Gatsby, contemplating life's existential quandaries while sipping illicit libations, became ubiquitous. Yet, rein in your enthusiasm, dear friends, for beneath the veneer of opulence and allure lurked a narrative more intricate than a daytime melodrama. Indeed, we reveled in our jazz-infused soirées and clandestine watering holes. Still, let's not overlook the darker undertones—the pervasive discrimination, economic disparity, and the ominous presence of the Ku Klux Klan, emboldened as though they had won life's lottery.

Now, let's dissect the economic landscape. You had visionaries like Henry Ford reshaping the automotive industry, rendering automobiles as common as winter colds. However, while the affluent reveled in luxury, the toiling masses ate a living akin to crumbs beneath a magnate's banquet table. Income inequality? It flourished with unwavering vitality. Cultural revolution, you say? Flappers defying societal norms as jazz melodies reverberated in the background? Indeed, such rebellion transpired. The flappers emerged, adorning cropped hairdos, puffing on cigarettes with abandon, and challenging Victorian propriety. And jazz? It served as the anthem of revolution, transcending racial boundaries and igniting a fervor that set hips swaying.

Yet, let us not gloss over the unsavory aspects. The Klan's resurgence disseminated vitriol like confetti at a celebration. African Americans endured relentless discrimination, the thickness of which could rival a chainsaw's blade. Jim Crow laws? Lynchings? Yes, they stained the fabric of society, casting a grim shadow over the era.

Now, onto Prohibition—a well-intentioned endeavor devolving into a bacchanalian spree. The 18th Amendment sought to curb alcohol consumption, only to catalyze an era rife with clandestine watering holes and bootleg liquor. It resembled the lawlessness of the frontier, albeit with flappers and Tommy guns instead of cowboys and revolvers.

So, what is the crux of this narrative? The 1920s may have been a carnival of delights, but they also served as a sobering reminder that behind every revelry lies the specter of consequence. It was a decade as intricate as a Rubik's Cube drenched in hot sauce—replete with contradictions, strife, and a generous dose of intoxicating drama. Yet, it provided fodder for discourse, did it not?

Or, in other words:

The 1920s was a decade of so roaring that even a tiger's yawn could be mistaken for a church bell's chime. Envision this: flappers fluttering, jazz aficionados improvising, and the stock market ascending to heights rivaling a pterodactyl fueled by energy drinks. It was an epoch where the aspiration of emulating Jay Gatsby, contemplating life's existential quandaries while sipping illicit libations, became ubiquitous. Yet, rein in your enthusiasm, dear friends, for beneath the veneer of opulence and allure lurked a narrative more intricate than a daytime melodrama. Indeed, we reveled in our jazz-infused soirées and clandestine watering holes. Still, let's not overlook the darker undertones—the pervasive discrimination, economic disparity, and the ominous presence of the Ku Klux Klan, emboldened as though they had won life's lottery.

Now, let's dissect the economic landscape. You had visionaries like Henry Ford reshaping the automotive industry, rendering automobiles as common as winter colds. However, while the affluent reveled in luxury, the toiling masses ate a living akin to crumbs beneath a magnate's banquet table. Income inequality? It flourished with unwavering vitality. Cultural revolution, you say? Flappers defying societal norms as jazz melodies reverberated in the background? Indeed, such rebellion transpired. The flappers emerged, adorning cropped hairdos, puffing on cigarettes with abandon, and challenging Victorian propriety. And jazz? It served as the anthem of revolution, transcending racial boundaries and igniting a fervor that set hips swaying.

Yet, let us not gloss over the unsavory aspects. The Klan's resurgence disseminated vitriol like confetti at a celebration. African Americans endured relentless discrimination, the thickness of which could rival a chainsaw's blade. Jim Crow laws? Lynchings? Yes, they stained the fabric of society, casting a grim shadow over the era.

Now, onto Prohibition—a well-intentioned endeavor devolving into a bacchanalian spree. The 18th Amendment sought to curb alcohol consumption, only to catalyze an era rife with clandestine watering holes and bootleg liquor. It resembled the lawlessness of the frontier, albeit with flappers and Tommy guns instead of cowboys and revolvers.

So, what is the crux of this narrative? The 1920s may have been a carnival of delights, but they also served as a sobering reminder that behind every revelry lies the specter of consequence. It was a decade as intricate as a Rubik's Cube drenched in hot sauce—replete with contradictions, strife, and a generous dose of intoxicating drama. Yet, it provided fodder for discourse, did it not?

Or, in other words:

- The 1920s in the United States witnessed unprecedented economic prosperity driven by technological innovations and increased consumerism, exemplified by the booming stock market and the widespread adoption of assembly-line production techniques.

- Cultural upheaval reshaped national identity through the emergence of the "flapper" lifestyle, jazz music, and mass media, challenging traditional norms and values while celebrating youth and innovation.

- Technological advances such as radio, cinema, and automobiles revolutionized communication and transportation, transforming both urban and rural landscapes.

- Despite the era's prosperity, deep-rooted issues of income inequality, discrimination, and social injustice persisted, exemplified by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the systemic racism faced by African Americans.

- Progressive reformers like W.E.B. Du Bois and Jane Addams fought for social justice, advocating for civil rights, women's suffrage, and labor rights amidst societal challenges.

- Historical events like Prohibition illustrate the complexities of the era, highlighting the unintended consequences of government regulation and the resilience of underground economies, while disproportionately affecting marginalized communities

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #6

- Forum Discussion #6

Forum Discussion #6

"Steamboat Willie," directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks in 1928, is an iconic animated short film in America. Not only is it recognized as the debut of beloved characters Mickey Mouse and Minnie, but it also is the pioneering accurate sound cartoon. Premiering on November 18, 1928, the film garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success. Serving as the inaugural installment in a series of over 150 Mickey Mouse films, it is a significant milestone in animation history. Noteworthy for its synchronized sound and incorporation of the existing tune "Steamboat Bill," the film also showcases innovative sound effects, further solidifying its place in cinematic history.What the short film and then answer the following:

"What are your thoughts on the historical significance and impact of 'Steamboat Willie' on the animation industry? How do you think the synchronized sound and use of pre-existing music in the film influenced the future of animation and the development of the character of Mickey Mouse?"

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

In the depths of "Steamboat Willie," Mickey Mouse grapples not just with navigating the Mississippi River but also with life's existential puzzles, embodying a spirit of courage amidst the chaos. Constrained to a humble steamboat job alongside the cantankerous Pete, Mickey juggles loading cargo, evading outbursts, and navigating the added tension of Minnie's presence. As comedic calamities ensue, from a foul-mouthed parrot to unreliable machinery, Mickey's perseverance shines, reflecting the enduring lessons of resilience and determination. Despite Pete's gruff leadership and Minnie's charming disruptions, Mickey's unwavering resolve, akin to a lion's heart and a cockroach's tenacity, propels him forward. Through this animated odyssey, Mickey's journey serves as a beacon of hope, reminding us that amidst life's storms, courage and resilience can illuminate the path forward.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.