Module Thirteen: Great Lakes & Great Minds

Michigan, the state where technology and chaos waltz together like a clumsy pair at a dance competition. Come closer, my friend, and let's stroll down the tangled paths of Michigan's technological past. But be warned, you might need a hazmat suit to navigate this mess.

Imagine this: the early 20th century, when Michigan was flexing its muscles in industry like an overzealous weightlifter. The rise of the automotive sector transformed Detroit into the "Motor City," where dreams were put together on assembly lines quicker than you could say "V8 engine." Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler—the trio that put American cars on the map—brought prosperity to the state faster than you could master a "Michigan left" turn.

But hold your applause because where there's silver, a cloud of pollution often hangs over it. The rapid industrialization birthed environmental headaches that would make Mother Nature groan. Pollution? Check. Fossil fuel addiction? Double check. Michigan's love affair with cars was like a messy breakup—it looked glamorous, but it left behind some serious baggage.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and Michigan's tech tale takes a dark twist. Enter the Flint water crisis, a bureaucratic blunder that even Kafka would find absurd. To save a buck, officials switched the city's water source, unleashing lead poisoning quicker than you could say "bottled water."

Sure, it sparked conversations about infrastructure and public health, but at what cost? Lives were disrupted, trust shattered, and Michigan's reputation took a hit worse than a Ford Pinto in a fender bender. It's a reminder that progress often comes with a side of consequences, and it's the ordinary folks who end up paying the price.

But fear not, for Michigan is diving into the digital realm amidst the chaos like a pro. Universities and research centers are churning out innovations hotter than a jalapeño at a chili cook-off, attracting talent and diversifying the economy faster than you can say, "Silicon Valley, who?"

Yet, for every digital leap, there's someone left behind by the march of progress, wondering where their job went quicker than you can say "automation." Michigan's journey through the digital age is like a high-stakes poker game—you win some, you lose some, and sometimes you're left with a handful of jokers.

So, what's the moral of this chaotic tale? Well, it's like life itself—a wild ride through the highs of innovation and the lows of unintended consequences. Grab your seatbelt because as long as humans are tinkering with tech, there'll be stories to tell—and Michigan's one story to share.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

Imagine this: the early 20th century, when Michigan was flexing its muscles in industry like an overzealous weightlifter. The rise of the automotive sector transformed Detroit into the "Motor City," where dreams were put together on assembly lines quicker than you could say "V8 engine." Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler—the trio that put American cars on the map—brought prosperity to the state faster than you could master a "Michigan left" turn.

But hold your applause because where there's silver, a cloud of pollution often hangs over it. The rapid industrialization birthed environmental headaches that would make Mother Nature groan. Pollution? Check. Fossil fuel addiction? Double check. Michigan's love affair with cars was like a messy breakup—it looked glamorous, but it left behind some serious baggage.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and Michigan's tech tale takes a dark twist. Enter the Flint water crisis, a bureaucratic blunder that even Kafka would find absurd. To save a buck, officials switched the city's water source, unleashing lead poisoning quicker than you could say "bottled water."

Sure, it sparked conversations about infrastructure and public health, but at what cost? Lives were disrupted, trust shattered, and Michigan's reputation took a hit worse than a Ford Pinto in a fender bender. It's a reminder that progress often comes with a side of consequences, and it's the ordinary folks who end up paying the price.

But fear not, for Michigan is diving into the digital realm amidst the chaos like a pro. Universities and research centers are churning out innovations hotter than a jalapeño at a chili cook-off, attracting talent and diversifying the economy faster than you can say, "Silicon Valley, who?"

Yet, for every digital leap, there's someone left behind by the march of progress, wondering where their job went quicker than you can say "automation." Michigan's journey through the digital age is like a high-stakes poker game—you win some, you lose some, and sometimes you're left with a handful of jokers.

So, what's the moral of this chaotic tale? Well, it's like life itself—a wild ride through the highs of innovation and the lows of unintended consequences. Grab your seatbelt because as long as humans are tinkering with tech, there'll be stories to tell—and Michigan's one story to share.

THE RUNDOWN

- Michigan's technological journey resembles a rollercoaster ride, from the roaring success of the automotive industry's heyday to the modern-day challenges of digital innovation.

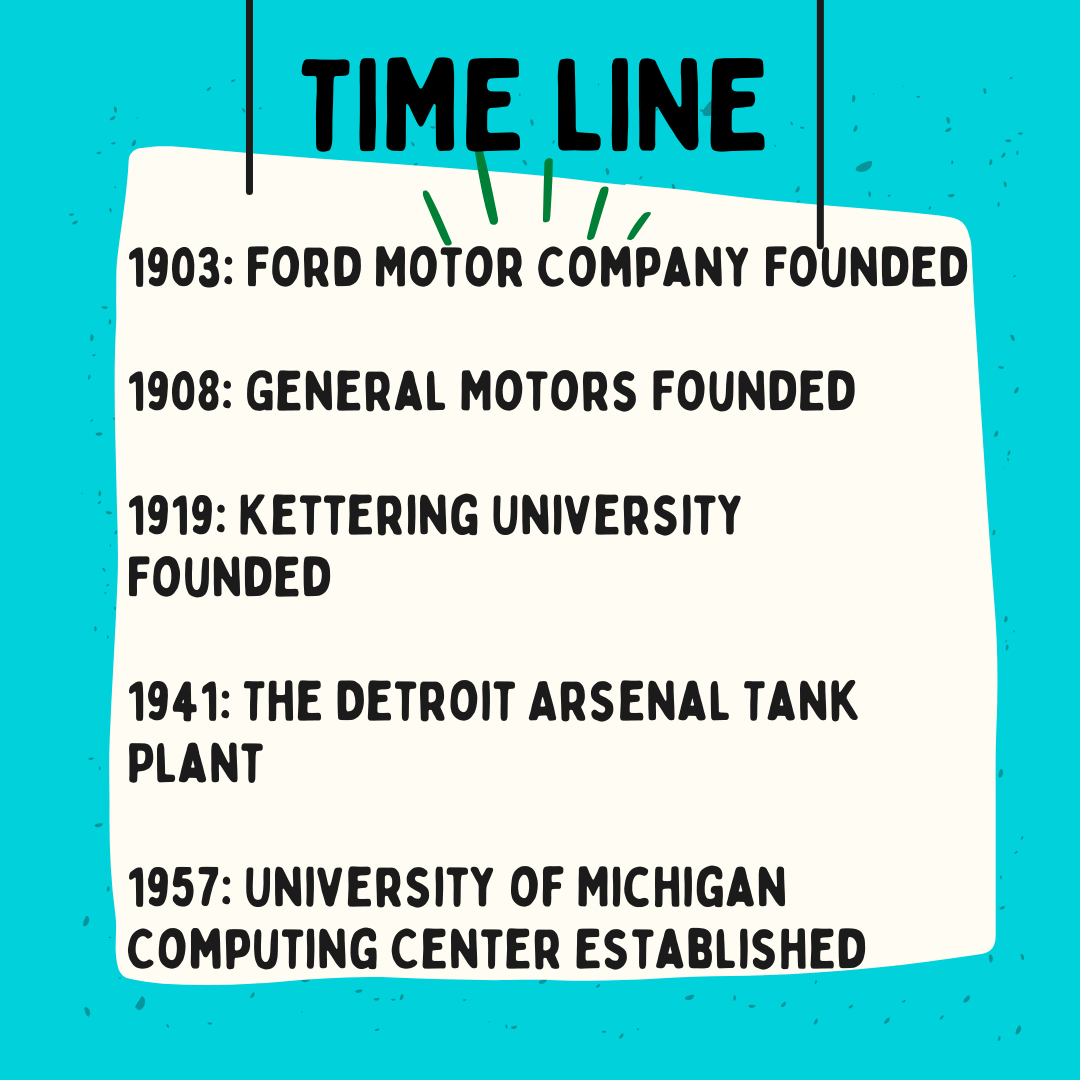

- The state's early embrace of automotive manufacturing catapulted it into prosperity, establishing Detroit as the renowned "Motor City" with giants like Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler leading the charge.

- However, this rapid industrialization came with environmental repercussions, showcasing the downside of technological advancement with issues like pollution and fossil fuel dependency.

- In more recent times, Michigan's tech landscape has seen both triumph and turmoil, epitomized by events like the Flint water crisis, highlighting the intersection of technology, governance, and public welfare.

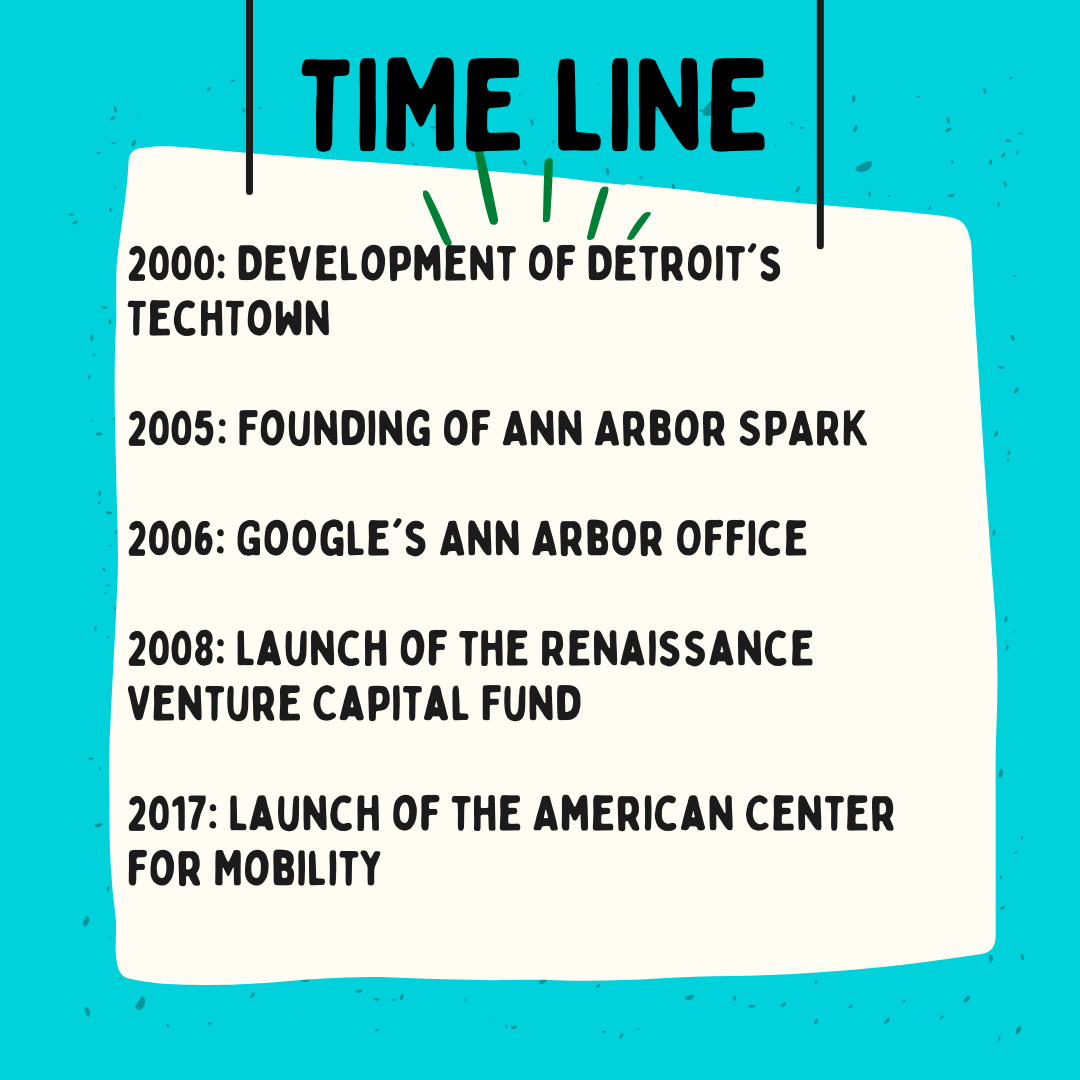

- Despite setbacks, Michigan is embracing the digital age with fervor, with universities and research institutions driving innovation and diversification, akin to emerging tech hubs like Silicon Valley.

- Yet, this digital leap isn't without its challenges, as automation and job displacement loom large, underscoring the complexities of navigating technological progress in a rapidly evolving world.

QUESTIONS

- Can you explain the Flint water crisis and its implications for both technology and public health in Michigan?

- How has Michigan's approach to technology evolved from the automotive era to the digital age?

- What are some examples of technological innovations coming out of Michigan's universities and research institutions?

#13 History Can Be Exceptional, But Not Virtuous

The grand tapestry of history, woven with threads of exceptionalism and virtue, or, as I like to call it, the eternal struggle between progress and moral bankruptcy. Strap in, folks, because we're about to take a wild ride through the annals of time, where the heroes are flawed, the villains are complex, and the whole thing is messier than a spaghetti-eating contest on a roller coaster.

Let's kick off with the chart-toppers, shall we? The Industrial Revolution was that awe-inspiring phenomenon that ushered in the contemporary era like a bawling infant fed on coal. Sure, it birthed steam engines, factories, and an economic boom that would make even Scrooge McDuck blush with envy, but let's not gloss over the less glamorous bits. Think child labor, sweatshops hotter than the devil's hot tub, and wealth chasms vast enough to accommodate the entire ensemble of "Hamilton" dancing sideways.

And then there's the Renaissance, where artists, intellectuals, and philosophers were popping up like champagne corks at a celebrity wedding. It was all "Da Vinci this" and "Michelangelo that," with Galileo dropping truth bombs like confetti. But let's face it, folks. For every masterpiece adorning the galleries, a hundred peasants were enduring the boot of feudalism. Ah, progress.

Next up are the gallant protagonists of our saga, the valiant few who stare down injustice with the audacity of David giving Goliath the double deuces. Enter the Civil Rights Movement, where luminaries like MLK Jr. and Rosa Parks dropped truth bombs quicker than a rapper on caffeine. They confronted segregation as if it were an overzealous chihuahua and didn't flinch. But let's not overlook the sobering reality that for every Rosa Parks, there were a thousand unsung heroes whose names never graced the pages of history. The struggle persists.

And then, there's the shadowy underbelly where virtue takes a sabbatical, and humanity plunges headlong into the abyss. Consider the Holocaust, a grotesque horror show that would make Freddy Krueger resemble a cuddly toy. Six million souls extinguished like candles in a tempest, all in the name of some twisted ideology concocted by a certain mustachioed maniac. It's enough to shake one's faith in humanity quicker than a vegan at a barbecue joint.

So, what's the moral of this topsy-turvy narrative? Well, dear comrades, history is a grab bag of assorted nuts, with the occasional nugget of virtue floating amidst a sea of peanuts. It's messy, convoluted, and as straightforward as a politician's pledge. It's our story, warts and all.

RUNDOWN

STATE OF THE STATE

Let's kick off with the chart-toppers, shall we? The Industrial Revolution was that awe-inspiring phenomenon that ushered in the contemporary era like a bawling infant fed on coal. Sure, it birthed steam engines, factories, and an economic boom that would make even Scrooge McDuck blush with envy, but let's not gloss over the less glamorous bits. Think child labor, sweatshops hotter than the devil's hot tub, and wealth chasms vast enough to accommodate the entire ensemble of "Hamilton" dancing sideways.

And then there's the Renaissance, where artists, intellectuals, and philosophers were popping up like champagne corks at a celebrity wedding. It was all "Da Vinci this" and "Michelangelo that," with Galileo dropping truth bombs like confetti. But let's face it, folks. For every masterpiece adorning the galleries, a hundred peasants were enduring the boot of feudalism. Ah, progress.

Next up are the gallant protagonists of our saga, the valiant few who stare down injustice with the audacity of David giving Goliath the double deuces. Enter the Civil Rights Movement, where luminaries like MLK Jr. and Rosa Parks dropped truth bombs quicker than a rapper on caffeine. They confronted segregation as if it were an overzealous chihuahua and didn't flinch. But let's not overlook the sobering reality that for every Rosa Parks, there were a thousand unsung heroes whose names never graced the pages of history. The struggle persists.

And then, there's the shadowy underbelly where virtue takes a sabbatical, and humanity plunges headlong into the abyss. Consider the Holocaust, a grotesque horror show that would make Freddy Krueger resemble a cuddly toy. Six million souls extinguished like candles in a tempest, all in the name of some twisted ideology concocted by a certain mustachioed maniac. It's enough to shake one's faith in humanity quicker than a vegan at a barbecue joint.

So, what's the moral of this topsy-turvy narrative? Well, dear comrades, history is a grab bag of assorted nuts, with the occasional nugget of virtue floating amidst a sea of peanuts. It's messy, convoluted, and as straightforward as a politician's pledge. It's our story, warts and all.

RUNDOWN

- History's exceptional events, like the Industrial Revolution, often drive progress but can also perpetuate inequalities and exploitation.

- Virtuous acts in history, such as those seen in the Civil Rights Movement, inspire positive change and promote social justice.

- Neglecting historical virtue, as evidenced by the Holocaust, can lead to moral complacency and the perpetuation of injustice.

- Understanding both exceptionalism and virtue in history equips individuals with insights into human behavior and moral responsibility.

- Through critical examination of historical events, individuals gain tools to confront contemporary challenges and shape a more just future.

- Studying history's dual nature fosters empathy, moral discernment, and a deeper understanding of the complexities of the past.

STATE OF THE STATE

HIGHLIGHTS

We've got some fine classroom lectures coming your way, all courtesy of the RPTM podcast. These lectures will take you on a wild ride through history, exploring everything from ancient civilizations and epic battles to scientific breakthroughs and artistic revolutions. The podcast will guide you through each lecture with its no-nonsense, straight-talking style, using various sources to give you the lowdown on each topic. You won't find any fancy-pants jargon or convoluted theories here, just plain and straightforward explanations anyone can understand. So sit back and prepare to soak up some knowledge.

LECTURES

LECTURES

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION!

READING

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Hathaway, Richard J. Michigan Visions of Our Past. United States Of America: Michigan State University Press, 1989.

"Michigan: Visions of Our Past" is an exhilarating adventure through the state's eventful history, led by scholars like Hathaway wielding the tools of the past. This collection reads like a diverse assortment of exciting stories and surprising revelations, providing a non-linear exploration of Michigan's struggle with its identity – be it navigating labor disputes, economic ups and downs, or the enduring conflict between religion and education. The book, resembling more of a mind-bending trip than a traditional history lesson, reflects Michigan's tumultuous history, encouraging readers to recognize that history is not merely a forgotten tome but a guidebook for the state's uncertain future. In this unconventional narrative, Michigan's history unfolds as a disorderly, absurd spectacle – a turbulent, unpredictable journey that embraces idiosyncrasies, confronts challenges, and invites everyone to the lively celebration of the past.

- Hathaway Chapter Seven: Michigan in the Gilded Age: Politics and Society, 1866-1900s

This class utilizes the following textbook:

Hathaway, Richard J. Michigan Visions of Our Past. United States Of America: Michigan State University Press, 1989.

"Michigan: Visions of Our Past" is an exhilarating adventure through the state's eventful history, led by scholars like Hathaway wielding the tools of the past. This collection reads like a diverse assortment of exciting stories and surprising revelations, providing a non-linear exploration of Michigan's struggle with its identity – be it navigating labor disputes, economic ups and downs, or the enduring conflict between religion and education. The book, resembling more of a mind-bending trip than a traditional history lesson, reflects Michigan's tumultuous history, encouraging readers to recognize that history is not merely a forgotten tome but a guidebook for the state's uncertain future. In this unconventional narrative, Michigan's history unfolds as a disorderly, absurd spectacle – a turbulent, unpredictable journey that embraces idiosyncrasies, confronts challenges, and invites everyone to the lively celebration of the past.

Howard Zinn was a historian, writer, and political activist known for his critical analysis of American history. He is particularly well-known for his counter-narrative to traditional American history accounts and highlights marginalized groups' experiences and perspectives. Zinn's work is often associated with social history and is known for his Marxist and socialist views. Larry Schweikart is also a historian, but his work and perspective are often considered more conservative. Schweikart's work is often associated with military history, and he is known for his support of free-market economics and limited government. Overall, Zinn and Schweikart have different perspectives on various historical issues and events and may interpret historical events and phenomena differently. Occasionally, we will also look at Thaddeus Russell, a historian, author, and academic. Russell has written extensively on the history of social and cultural change, and his work focuses on how marginalized and oppressed groups have challenged and transformed mainstream culture. Russell is known for his unconventional and controversial ideas, and his work has been praised for its originality and provocative nature.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules.

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules.

Zinn, A People's History of the United States

"... The removal of the Indians was explained by Lewis Cass-Secretary of War, governor of the Michigan territory, minister to France, presidential candidate:

A principle of progressive improvement seems almost inherent in human nature. . .. We are all striving in the career of life to acquire riches of honor, or power, or some other object, whose possession is to realize the day dreams of our imaginations; and the aggregate of these efforts constitutes the advance of society. But there is little of this in the constitution of our savages.

Cass-pompous, pretentious, honored (Harvard gave him an honorary doctor of laws degree in 1836, at the height of Indian removal)- claimed to be an expert on the Indians. But he demonstrated again and again, in Richard Drinnon's words (Violence in the American Experience: Winning the West), a "quite marvelous ignorance of Indian life." As governor of the Michigan Territory, Cass took millions of acres from the Indians by treaty: "We must frequently promote their interest against their inclination."

His article in the North American Review in 1830 made the case for Indian Removal. We must not regret, he said, 'the progress of civilization and improvement, the triumph of industry and art, by which these regions have been reclaimed, and over which freedom, religion, and science are extending their sway.' He wished that all this could have been done with 'a smaller sacrifice; that the aboriginal population had accommodated themselves to the inevitable change of their condition... . But such a wish is vain. A barbarous people, depending for subsistence upon the scanty and precarious supplies furnished by the chase, cannot live in contact with a civilized community.'..."

"... The removal of the Indians was explained by Lewis Cass-Secretary of War, governor of the Michigan territory, minister to France, presidential candidate:

A principle of progressive improvement seems almost inherent in human nature. . .. We are all striving in the career of life to acquire riches of honor, or power, or some other object, whose possession is to realize the day dreams of our imaginations; and the aggregate of these efforts constitutes the advance of society. But there is little of this in the constitution of our savages.

Cass-pompous, pretentious, honored (Harvard gave him an honorary doctor of laws degree in 1836, at the height of Indian removal)- claimed to be an expert on the Indians. But he demonstrated again and again, in Richard Drinnon's words (Violence in the American Experience: Winning the West), a "quite marvelous ignorance of Indian life." As governor of the Michigan Territory, Cass took millions of acres from the Indians by treaty: "We must frequently promote their interest against their inclination."

His article in the North American Review in 1830 made the case for Indian Removal. We must not regret, he said, 'the progress of civilization and improvement, the triumph of industry and art, by which these regions have been reclaimed, and over which freedom, religion, and science are extending their sway.' He wished that all this could have been done with 'a smaller sacrifice; that the aboriginal population had accommodated themselves to the inevitable change of their condition... . But such a wish is vain. A barbarous people, depending for subsistence upon the scanty and precarious supplies furnished by the chase, cannot live in contact with a civilized community.'..."

Larry Schweikart, A Patriot's History of the United States

"... Spaniards traversed modern-day Mexico, probing interior areas under Hernando Cortés, who in 1518 led a force of 1,000 soldiers to Tenochtitlán, the site of present-day Mexico City. Cortés encountered powerful Indians called Aztecs, led by their emperor Montezuma. The Aztecs had established a brutal regime that oppressed other natives of the region, capturing large numbers of them for ritual sacrifices in which Aztec priests cut out the beating hearts of living victims. Such barbarity enabled the Spanish to easily enlist other tribes, especially the Tlaxcalans, in their efforts to defeat the Aztecs.

Tenochtitlán sat on an island in the middle of a lake, connected to the outlying areas by three huge causeways. It was a monstrously large city (for the time) of at least 200,000, rigidly divided into nobles and commoner groups.14 Aztec culture created impressive pyramid-shaped temple structures, but Aztec science lacked the simple wheel and the wide range of pulleys and gears that it enabled. But it was sacrifice, not science, that defined Aztec society, whose pyramids, after all, were execution sites. A four-day sacrifice in 1487 by the Aztec king Ahuitzotl involved the butchery of 80,400 prisoners by shifts of priests working four at a time at convex killing tables who kicked lifeless, heartless bodies down the side of the pyramid temple. This worked out to a 'killing rate of fourteen victims a minute over the ninety-six-hour bloodbath.' In addition to the abominable sacrifice system, crime and street carnage were commonplace. More intriguing to the Spanish than the buildings, or even the sacrifices, however, were the legends of gold, silver, and other riches Tenochtitlán contained, protected by the powerful Aztec army..."

"... Spaniards traversed modern-day Mexico, probing interior areas under Hernando Cortés, who in 1518 led a force of 1,000 soldiers to Tenochtitlán, the site of present-day Mexico City. Cortés encountered powerful Indians called Aztecs, led by their emperor Montezuma. The Aztecs had established a brutal regime that oppressed other natives of the region, capturing large numbers of them for ritual sacrifices in which Aztec priests cut out the beating hearts of living victims. Such barbarity enabled the Spanish to easily enlist other tribes, especially the Tlaxcalans, in their efforts to defeat the Aztecs.

Tenochtitlán sat on an island in the middle of a lake, connected to the outlying areas by three huge causeways. It was a monstrously large city (for the time) of at least 200,000, rigidly divided into nobles and commoner groups.14 Aztec culture created impressive pyramid-shaped temple structures, but Aztec science lacked the simple wheel and the wide range of pulleys and gears that it enabled. But it was sacrifice, not science, that defined Aztec society, whose pyramids, after all, were execution sites. A four-day sacrifice in 1487 by the Aztec king Ahuitzotl involved the butchery of 80,400 prisoners by shifts of priests working four at a time at convex killing tables who kicked lifeless, heartless bodies down the side of the pyramid temple. This worked out to a 'killing rate of fourteen victims a minute over the ninety-six-hour bloodbath.' In addition to the abominable sacrifice system, crime and street carnage were commonplace. More intriguing to the Spanish than the buildings, or even the sacrifices, however, were the legends of gold, silver, and other riches Tenochtitlán contained, protected by the powerful Aztec army..."

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States

"... In the 1920s, the offices in the buildings along the eastern edge of the Columbia University campus looked from the hills of Morningside Heights out over Harlem. Rexford Tugwell, a professor in the economics department, occupied one of those offices. From behind his desk in Hamilton Hall, Tugwell could not hear the music but he could see the nightclubs, dance halls, and speakeasies that defined the Jazz Age. And so he waited.

Tugwell had been shut off from the pleasures of the body as a child, when asthma and persistent illnesses kept him confined to bed in his rural and isolated hometown in far-western New York State. He grew into an extraordinarily handsome man, with the dark looks and wavy hair of a silent-screen star. But his illnesses continued, and by the time he reached maturity, he had retreated into a world of books. He was a fan of utopian science fiction, such as H. G. Wells’s In the Days of the Comet, in which mankind, fearing destruction from an onrushing comet, remakes world society into a cooperative commune. Tugwell spent much of his youth conjuring perfect worlds inhabited by perfect people. As an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1910s, he fell under the spell of the young economics professor Scott Nearing, who had recently published a book calling for the creation of just such a world. “The kind of social philosophy I was developing under the tutelage of Nearing, reinforced by other instruction,” Tugwell later recalled in his autobiography, “is perhaps best defined in a little book called The Super Race: An American Problem, which Nearing published in 1912.” Nearing argued that the United States should develop, through selective breeding, a race of supermen who would create the world’s first utopia. These ideas, which were bastardized versions of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy, were then in vogue among German intellectuals who would become the intellectual founders of Nazism.

Tugwell’s other mentor in college was the prominent progressive economist Simon Patten, who had been trained in German universities. “He taught me the importance of looking for uniformities, laws, explanations of the inner forces moving behind the façade of events,” Tugwell remembered. “One of these was the conclusion that our pluralistic system—laissez-faire in industry, checks and balances in government, and so on—must be shaped into a unity if its inherent conflicts, beginning to be so serious, were not to destroy us.” From where did Patten get this benign sounding idea? “He thought that the Germans had the key to that unity in philosophy, in economics, and perhaps in politics. He saw the conflict, now so ominously coming up over the horizon, as one between the living wholeness of the German conception and the dying divisiveness of English pluralism.” Even more ominous was the belief that Patten shared with his German colleagues—who would supply the intellectual basis for Nazism—that industrial capitalism and technological advances had softened and emasculated the people. “Every improvement which simplifies or lessens manual labor,” explained Patten, “increases the amount of the deficiencies which the laboring classes may possess without their being thereby overcome in the struggle for subsistence that the survival of the ignorant brings upon society.” Patten’s solution to this problem was swift, simple, and breathtakingly ruthless. “Social progress is a higher law than equality, and a nation must choose it at any cost,” and the only way to progress is the “eradication of the vicious and inefficient.” But the prescriptions of Nearing and Patten were just academic wishes. Tugwell wished to make them real..."

"... In the 1920s, the offices in the buildings along the eastern edge of the Columbia University campus looked from the hills of Morningside Heights out over Harlem. Rexford Tugwell, a professor in the economics department, occupied one of those offices. From behind his desk in Hamilton Hall, Tugwell could not hear the music but he could see the nightclubs, dance halls, and speakeasies that defined the Jazz Age. And so he waited.

Tugwell had been shut off from the pleasures of the body as a child, when asthma and persistent illnesses kept him confined to bed in his rural and isolated hometown in far-western New York State. He grew into an extraordinarily handsome man, with the dark looks and wavy hair of a silent-screen star. But his illnesses continued, and by the time he reached maturity, he had retreated into a world of books. He was a fan of utopian science fiction, such as H. G. Wells’s In the Days of the Comet, in which mankind, fearing destruction from an onrushing comet, remakes world society into a cooperative commune. Tugwell spent much of his youth conjuring perfect worlds inhabited by perfect people. As an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1910s, he fell under the spell of the young economics professor Scott Nearing, who had recently published a book calling for the creation of just such a world. “The kind of social philosophy I was developing under the tutelage of Nearing, reinforced by other instruction,” Tugwell later recalled in his autobiography, “is perhaps best defined in a little book called The Super Race: An American Problem, which Nearing published in 1912.” Nearing argued that the United States should develop, through selective breeding, a race of supermen who would create the world’s first utopia. These ideas, which were bastardized versions of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy, were then in vogue among German intellectuals who would become the intellectual founders of Nazism.

Tugwell’s other mentor in college was the prominent progressive economist Simon Patten, who had been trained in German universities. “He taught me the importance of looking for uniformities, laws, explanations of the inner forces moving behind the façade of events,” Tugwell remembered. “One of these was the conclusion that our pluralistic system—laissez-faire in industry, checks and balances in government, and so on—must be shaped into a unity if its inherent conflicts, beginning to be so serious, were not to destroy us.” From where did Patten get this benign sounding idea? “He thought that the Germans had the key to that unity in philosophy, in economics, and perhaps in politics. He saw the conflict, now so ominously coming up over the horizon, as one between the living wholeness of the German conception and the dying divisiveness of English pluralism.” Even more ominous was the belief that Patten shared with his German colleagues—who would supply the intellectual basis for Nazism—that industrial capitalism and technological advances had softened and emasculated the people. “Every improvement which simplifies or lessens manual labor,” explained Patten, “increases the amount of the deficiencies which the laboring classes may possess without their being thereby overcome in the struggle for subsistence that the survival of the ignorant brings upon society.” Patten’s solution to this problem was swift, simple, and breathtakingly ruthless. “Social progress is a higher law than equality, and a nation must choose it at any cost,” and the only way to progress is the “eradication of the vicious and inefficient.” But the prescriptions of Nearing and Patten were just academic wishes. Tugwell wished to make them real..."

Michigan, where every step forward comes with a stumble back and a hearty dose of "what were they thinking?" Let's joyride through the state's tech history – it's like a sitcom with more rust and fewer laugh tracks. First up, Lewis Cass, the maestro behind the Trail of Tears disaster. Because who needs diplomacy when you can shuffle indigenous folks around like chess pieces? It was a smooth move, Cass, really soft. Next time, could you try negotiation instead of relocation?

Then there's Hernan Cortés, the OG tech enthusiast of the 1500s. He is bringing European gadgets to the Americas like he's unveiling the latest gadgets at a tech expo. "Hey Aztecs, check out these shiny toys and surprise diseases – compliments of progress!" Spoiler alert: it didn't end well for the locals. Progress marches on, right? Jumping ahead to the 1930s, enter Rexford Tugwell, the guy who thought he could fix everything with New Deal schemes. Nothing says "let's shake things up," like revamping farming and hiring people for the Civilian Conservation Corps. Sure, there were bumps in the road—like trampling on personal freedoms and not quite revolutionizing society—but hey, you win some, you lose some.

Could you dive into Michigan's tech past? Besides being a treasure trove of cautionary tales about power gone haywire and innovation gone off the rails, it's a reminder of our knack for brilliance and blunders. By facing up to our history, we can dodge the same messes in the future. Plus, it beats the snooze-fest of the latest iPhone updates any day. So there you have it, folks—Michigan's tech saga is a rollercoaster of progress, power struggles, and plenty of facepalms. Buckle up because this ride's a doozy. And remember, sometimes you gotta glance back to move forward—with a pinch of skepticism and a dash of dark humor.

THE RUNDOWN

QUESTIONS

Then there's Hernan Cortés, the OG tech enthusiast of the 1500s. He is bringing European gadgets to the Americas like he's unveiling the latest gadgets at a tech expo. "Hey Aztecs, check out these shiny toys and surprise diseases – compliments of progress!" Spoiler alert: it didn't end well for the locals. Progress marches on, right? Jumping ahead to the 1930s, enter Rexford Tugwell, the guy who thought he could fix everything with New Deal schemes. Nothing says "let's shake things up," like revamping farming and hiring people for the Civilian Conservation Corps. Sure, there were bumps in the road—like trampling on personal freedoms and not quite revolutionizing society—but hey, you win some, you lose some.

Could you dive into Michigan's tech past? Besides being a treasure trove of cautionary tales about power gone haywire and innovation gone off the rails, it's a reminder of our knack for brilliance and blunders. By facing up to our history, we can dodge the same messes in the future. Plus, it beats the snooze-fest of the latest iPhone updates any day. So there you have it, folks—Michigan's tech saga is a rollercoaster of progress, power struggles, and plenty of facepalms. Buckle up because this ride's a doozy. And remember, sometimes you gotta glance back to move forward—with a pinch of skepticism and a dash of dark humor.

THE RUNDOWN

- Michigan's technological history reveals complexities through events like Lewis Cass's advocacy for Indian Removal and the tragic Trail of Tears in 1830.

- Cass's advocacy led to lasting negative consequences for tribes, despite positive intentions.

- Hernan Cortés's conquest of Mexico in 1519 brought European technology but also exploitation and cultural erosion.

- Rexford Tugwell's influence on New Deal policies in the 1930s highlights the challenges of using technology for social change.

- Studying Michigan's technological history informs contemporary issues like social injustice and economic inequality.

- It also preserves indigenous heritage, guiding decisions for a more equitable future.

QUESTIONS

- In what ways does humor serve as a tool for examining the darker aspects of history, as seen in the portrayal of Michigan's technological past?

- Discuss the role of progress in the narrative. How is progress portrayed positively, and where do the drawbacks become evident?

- Explore the theme of power dynamics throughout Michigan's technological history. How do individuals or groups exert power, and what are the consequences?

Prepare to be transported into the captivating realm of historical films and videos. Brace yourselves for a mind-bending odyssey through time as we embark on a cinematic expedition. Within these flickering frames, the past morphs into a vivid tapestry of triumphs, tragedies, and transformative moments that have shaped the very fabric of our existence. We shall immerse ourselves in a whirlwind of visual narratives, dissecting the nuances of artistic interpretations, examining the storytelling techniques, and voraciously devouring historical accuracy with the ferocity of a time-traveling historian. So strap in, hold tight, and prepare to have your perception of history forever shattered by the mesmerizing lens of the camera.

THE RUNDOWN

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, a wellness pioneer, preaching the virtues of vegetarianism and exercise. At the same time, his brother Will Keith set his sights on breakfast domination. John established his health haven at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, an ironic choice given its name's battlefield connotation. Meanwhile, Will saw cornflakes not as a health revolution but as a golden opportunity for profit.

Amidst familial tensions and legal battles hotter than a fresh pancake, Will emerged victorious, propelling Kellogg's into household fame and forever changing breakfast routines. Once peas in a pod, the Kellogg brothers became cereal aisle rivals, their clash reminiscent of crunchy cornflakes in milk. Yet, amidst the drama, they provided a morning meal and a reflection on family dynamics, the American dream, and the whims of breakfast preferences.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, a wellness pioneer, preaching the virtues of vegetarianism and exercise. At the same time, his brother Will Keith set his sights on breakfast domination. John established his health haven at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, an ironic choice given its name's battlefield connotation. Meanwhile, Will saw cornflakes not as a health revolution but as a golden opportunity for profit.

Amidst familial tensions and legal battles hotter than a fresh pancake, Will emerged victorious, propelling Kellogg's into household fame and forever changing breakfast routines. Once peas in a pod, the Kellogg brothers became cereal aisle rivals, their clash reminiscent of crunchy cornflakes in milk. Yet, amidst the drama, they provided a morning meal and a reflection on family dynamics, the American dream, and the whims of breakfast preferences.

Welcome to the mind-bending Key Terms extravaganza of our history class learning module. Brace yourselves; we will unravel the cryptic codes, secret handshakes, and linguistic labyrinths that make up the twisted tapestry of historical knowledge. These key terms are the Rosetta Stones of our academic journey, the skeleton keys to unlocking the enigmatic doors of comprehension. They're like historical Swiss Army knives, equipped with blades of definition and corkscrews of contextual examples, ready to pierce through the fog of confusion and liberate your intellectual curiosity. By harnessing the power of these mighty key terms, you'll possess the superhuman ability to traverse the treacherous terrains of primary sources, surf the tumultuous waves of academic texts, and engage in epic battles of historical debate. The past awaits, and the key terms are keys to unlocking its dazzling secrets.

KEY TERMS

KEY TERMS

- 1854 - The Detroit Observatory

- 1897 - The Dow Chemical Company

- 1903 - Detroit Edison Company

- 1903 - Technology of Ford Motor Company

- 1907 - The Detroit Electric Car

- 1908 - General Motors Founded

- 1919 – Kettering University Founded

- 1925 - The Detroit Auto Show

- 1940 - The Michigan State University Cyclotron

- 1941 - Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant

- 1959 – Computing Center at the University of Michigan

- 1970 - Michigan Science Center

- 1971 - The Apollo 15 and Al Worden

- 1997 - Michigan's Modern Electric Vehicles

- 2000 - TechTown Launched

- 2004 - Ann Arbor SPARK

- 2005 - Michigan Merit Curriculum

- 2006 - Google Moves to Ann Arbor

- 2006 - The Michigan Tech Research Institute

- 2018 - The Michigan Environmental Science Board

DISCLAIMER: Welcome scholars to the wild and wacky world of history class. This isn't your granddaddy's boring ol' lecture, baby. We will take a trip through time, which will be one wild ride. I know some of you are in a brick-and-mortar setting, while others are in the vast digital wasteland. But fear not; we're all in this together. Online students might miss out on some in-person interaction, but you can still join in on the fun. This little shindig aims to get you all engaged with the course material and understand how past societies have shaped the world we know today. We'll talk about revolutions, wars, and other crazy stuff. So get ready, kids, because it's going to be one heck of a trip. And for all, you online students out there, don't be shy. Please share your thoughts and ideas with the rest of us. The Professor will do his best to give everyone an equal opportunity to learn, so don't hold back. So, let's do this thing!

Activity #1: UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Activity #2: UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Activity #1: UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Activity #2: UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round for the pièce de résistance of this classroom module - the summary section. As we embark on this tantalizing journey, we'll savor the exquisite flavors of knowledge, highlighting the fundamental ingredients and spices that have seasoned our minds throughout these captivating lessons. Prepare to indulge in a savory recap that will leave your intellectual taste buds tingling, serving as a passport to further enlightenment.

Welcome to the land where car dreams meet the harsh reality of life's potholes. You can just buckle up for a ride through the maze of technological advancements. We're diving into Michigan's history, where Henry Ford looms large like a titan of industry, turning dreams into exhaust fumes faster than you can say "assembly line."

Detroit, once the Motor City, churned out dreams alongside automobiles, mixing innovation with the stench of industry. Ah, progress! But hold your applause because where there's progress, there's usually a mess left behind. Take the Ford River Rouge Complex, once hailed as a temple of progress, now a shrine to environmental neglect. The Rouge River? It's more like the Rouge Ruiner, with pollution thick enough to slice with a hacksaw.

And then there's Flint. Oh, Flint. The 2014 water crisis turned into a full-blown disaster, a real-life game of Russian roulette with invisible bullets and innocent victims. Talk about bureaucratic chaos.

Fast-forward to today, and Michigan's tech scene buzzes like a beehive on overdrive. But with innovation comes responsibility, and automation's causing job havoc faster than you can say "unemployment."

Let's not overlook the Mackinac Bridge, an engineering marvel that spans progress and consequence. It reminds us of displaced communities and disrupted ecosystems, a bridge to the future built on the bones of the past.

So, what's the lesson here? Progress isn't always what it seems. Or perhaps it's just a shiny facade masking unintended consequences. Either way, Michigan's tech journey is a cautionary tale, reminding us that sometimes, progress comes with potholes. Welcome to the Motor City, where dreams are made, broken, and rebuilt, one revolution at a time.

Or, in other words:

Detroit, once the Motor City, churned out dreams alongside automobiles, mixing innovation with the stench of industry. Ah, progress! But hold your applause because where there's progress, there's usually a mess left behind. Take the Ford River Rouge Complex, once hailed as a temple of progress, now a shrine to environmental neglect. The Rouge River? It's more like the Rouge Ruiner, with pollution thick enough to slice with a hacksaw.

And then there's Flint. Oh, Flint. The 2014 water crisis turned into a full-blown disaster, a real-life game of Russian roulette with invisible bullets and innocent victims. Talk about bureaucratic chaos.

Fast-forward to today, and Michigan's tech scene buzzes like a beehive on overdrive. But with innovation comes responsibility, and automation's causing job havoc faster than you can say "unemployment."

Let's not overlook the Mackinac Bridge, an engineering marvel that spans progress and consequence. It reminds us of displaced communities and disrupted ecosystems, a bridge to the future built on the bones of the past.

So, what's the lesson here? Progress isn't always what it seems. Or perhaps it's just a shiny facade masking unintended consequences. Either way, Michigan's tech journey is a cautionary tale, reminding us that sometimes, progress comes with potholes. Welcome to the Motor City, where dreams are made, broken, and rebuilt, one revolution at a time.

Or, in other words:

- Michigan's history with technology shows how cars brought jobs and growth, but also pollution and problems.

- The Flint water crisis in 2014 made us see how technology and government decisions can hurt people's health.

- Today, Michigan is trying new tech ideas to create jobs and solve problems, but some worry it might take away jobs instead.

- Building the Mackinac Bridge helped travel and the economy, but it also hurt indigenous people and nature.

- Learning about Michigan's tech past helps us understand why things are like they are now and how to make them better.

- By looking at both good and bad events, we can learn how to use technology for good and avoid making the same mistakes.

ASSIGNMENTS

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #13

- Forum Discussion #13

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD

Forum Discussion #13

The Anything History YouTube channel provides concise and engaging historical narratives spanning various topics, delivering informative content with a creative and accessible approach. Watch the following video:

Please answer the following question:

How did the early 20th-century golden age of electric vehicles compare to the modern resurgence of interest in electric cars? What were the advantages and challenges faced by electric vehicles during both eras, and how do they reflect the evolving attitudes towards sustainability and transportation technology?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Once upon a time, in the Western Antique Airplane and Automotive Museum, nestled in Hood River, Oregon, a Detroit Electric car stood as a pristine relic of an era when innovation and engineering merged in automotive alchemy. Surrounded by roaring gas guzzlers, it painted a surreal picture of a bygone dream—when Edison and Ford envisioned silent streets and clear skies. Yet, despite the gasoline juggernaut's dominance, the electric dream flickers to life again. Classic cars are reborn with electric hearts, and icons like Harley-Davidson embrace the silent revolution. As nations ponder bans on gas guzzlers, the future gleams electric, promising an electrifying ride, reminding us that while the past is set, the future is ours to shape.

How did the early 20th-century golden age of electric vehicles compare to the modern resurgence of interest in electric cars? What were the advantages and challenges faced by electric vehicles during both eras, and how do they reflect the evolving attitudes towards sustainability and transportation technology?

Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

THE RUNDOWN

Once upon a time, in the Western Antique Airplane and Automotive Museum, nestled in Hood River, Oregon, a Detroit Electric car stood as a pristine relic of an era when innovation and engineering merged in automotive alchemy. Surrounded by roaring gas guzzlers, it painted a surreal picture of a bygone dream—when Edison and Ford envisioned silent streets and clear skies. Yet, despite the gasoline juggernaut's dominance, the electric dream flickers to life again. Classic cars are reborn with electric hearts, and icons like Harley-Davidson embrace the silent revolution. As nations ponder bans on gas guzzlers, the future gleams electric, promising an electrifying ride, reminding us that while the past is set, the future is ours to shape.

Hey, welcome to the work cited section! Here's where you'll find all the heavy hitters that inspired the content you've just consumed. Some might think citations are as dull as unbuttered toast, but nothing gets my intellectual juices flowing like a good reference list. Don't get me wrong, just because we've cited a source; doesn't mean we're always going to see eye-to-eye. But that's the beauty of it - it's up to you to chew on the material and come to conclusions. Listen, we've gone to great lengths to ensure these citations are accurate, but let's face it, we're all human. So, give us a holler if you notice any mistakes or suggest more sources. We're always looking to up our game. Ultimately, it's all about pursuing knowledge and truth.

Work Cited:

Work Cited:

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- (Disclaimer: This is not professional or legal advice. If it were, the article would be followed with an invoice. Do not expect to win any social media arguments by hyperlinking my articles. Chances are, we are both wrong).

- (Trigger Warning: This article or section, or pages it links to, contains antiquated language or disturbing images which may be triggering to some.)

- (Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is granted, provided that the author (or authors) and www.ryanglancaster.com are appropriately cited.)

- This site is for educational purposes only.

- Disclaimer: This learning module was primarily created by the professor with the assistance of AI technology. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, please note that the AI's contribution was limited to some regions of the module. The professor takes full responsibility for the content of this module and any errors or omissions therein. This module is intended for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice or consultation. The professor and AI cannot be held responsible for any consequences arising from using this module.

- Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

- Fair Use Definition: Fair use is a doctrine in United States copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission from the rights holders, such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, or scholarship. It provides for the legal, non-licensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.