|

Module Five: American Revolution Part 1 (1777 CE- 1794 CE)

Welcome to HST 201 Module Five! We are looking at the effects of the American Revolution on the North American landscape. Pay attention: this next part is crucial for you to understand the nuances of history. This is most likely my most important rule. Ultimately, I tell my students at the beginning of every semester. Rule Number Five of History is History is not monolithic. It is told through countless eyes and countless lenses. Unfortunately, this is the first thing to go when organizing historical thoughts. When building a timeline of events, the historian must separate the vital from the trivial and mundane. However, this becomes challenging to do objectively. Like it or not, our worldview decides what is important to us. And our worldview is formed from our backgrounds and our values. Knowing this, we tend to have our history spoon-fed from a specific demographic, generally upper-class white Christian men. Before you cancel me, I must stress that this is not an attack but merely an observation. Those stories are important. That history must be preserved and retold. But what about other demographics? When drudging through American history, we spend much of our time dissecting the slave economy of the 19th century, the butchering and abuses against the native Americans, and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Again, all pivotal moments in time and critical for understanding our past. But there is so much more out there that needs to be addressed. Asian American history and Latino history are, for the most part, nonexistent. Gay and Trans accounts are forgotten. Who was the first Muslim in the new world? The first Asians? Heck, what about the sports and games people played in the 17th century? All these concepts and stories beg to be addressed. I knew that publishers are limited to what they can include, especially at the hands of special interest groups and federal mandates in a textbook format. I am not tethered to that. This class can be whatever we shaped it into. It can grow and breathe as needed. And it will speak for the voiceless.

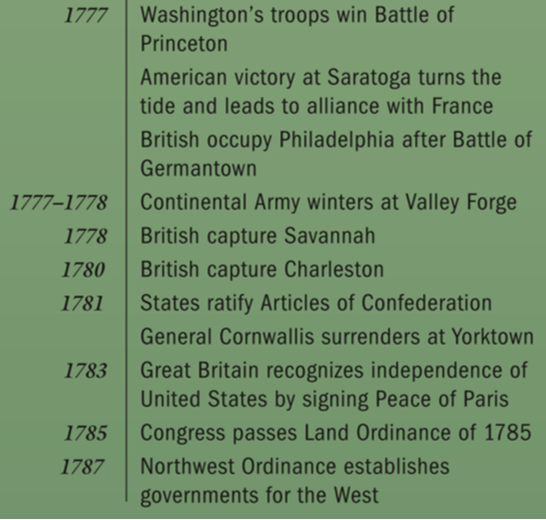

HIGHLIGHTS

LECTURES

#019 von Stueben, Gadsden, Yankee Doodle, and the End of the War (38:00) #020 The Fallout from the Revolution, the Founding Fathers, And the Treaty of Six Nations (32:55) #021 Shay’s Rebellion, Articles of Confederation, Northwest Ordinance, Constitution, and Homosexuality (37:49) #022 The Bald Eagle, The American Novel, Whiskey Rebellion, and Latinos (35:22) READING

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Zinn, Chapter 4 “Tyranny is Tyranny”

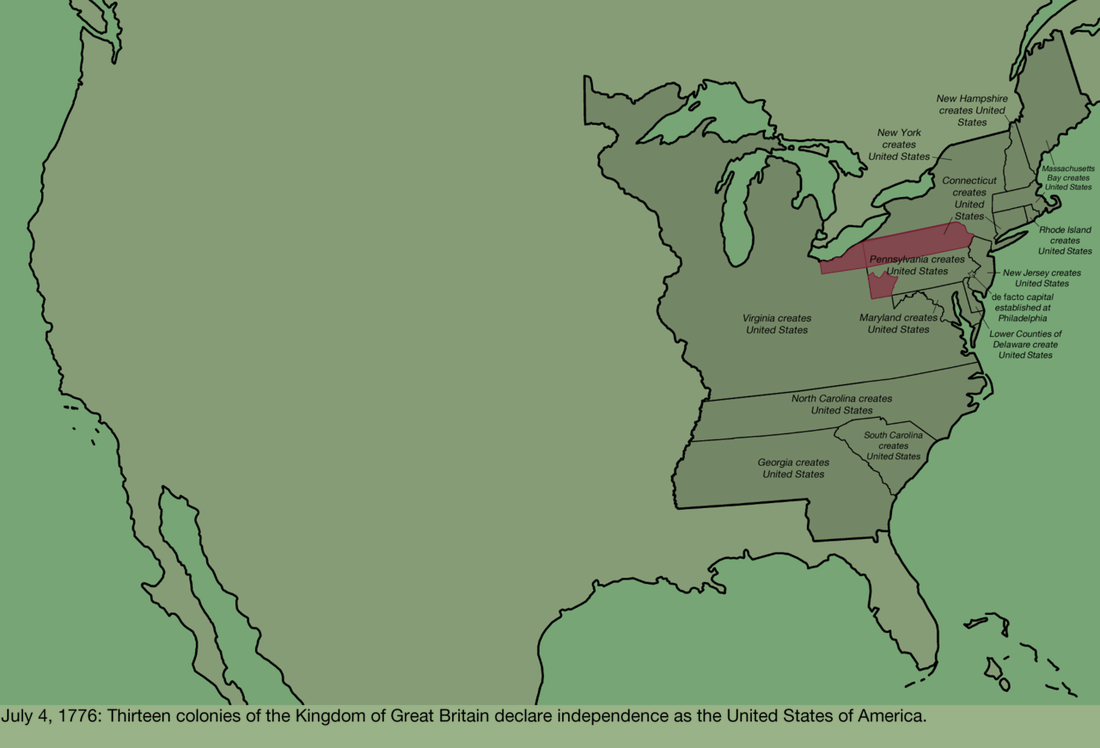

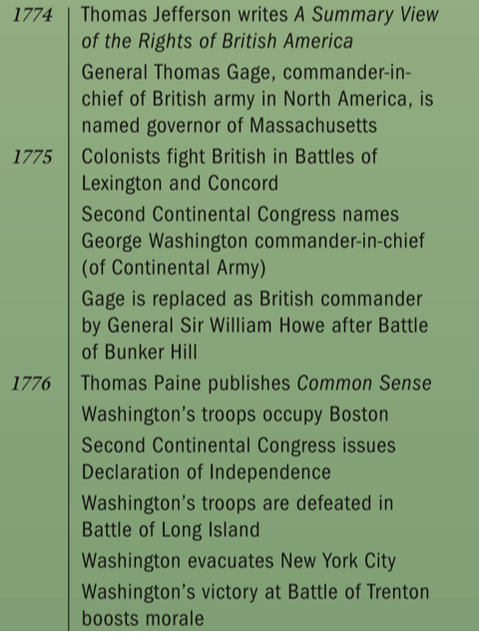

…During elections for the 1776 convention to frame a constitution for Pennsylvania, a Privates Committee urged voters to oppose "great and overgrown rich men… they will be too apt to be framing distinctions in society." The Privates Committee drew up a bill of rights for the convention, including the statement that "an enormous proportion of property vested in a few individuals is dangerous to the rights, and destructive of the common happiness, of mankind; and therefore every free state hath a right by its laws to discourage the possession of such property." In the countryside, where most people lived, there was a similar conflict of poor against rich, one which political leaders would use to mobilize the population against England, granting some benefits for the rebellious poor, and many more for themselves in the process. The tenant riots in New Jersey in the 1740s, the New York tenant uprisings of the 1750s and 1760s in the Hudson Valley, and the rebellion in northeastern New York that led to the carving of Vermont out of New York State were all more than sporadic rioting. They were long-lasting social movements, highly organized, involving the creation of counter governments. They were aimed at a handful of rich landlords, but with the landlords far away, they often had to direct their anger against farmers who had leased the disputed land from the owners. (See Edward Countryman's pioneering work on rural rebellion.) Just as the Jersey rebels had broken into jails to free their friends, rioters in the Hudson Valley rescued prisoners from the sheriff and one time took the sheriff himself as prisoner. The tenants were seen as "chiefly the dregs of the People," and the posse that the sheriff of Albany County led to Bennington in 1771 included the privileged top of the local power structure. The land rioters saw their battle as poor against rich. A witness at a rebel leader's trial in New York in 1766 said that the farmers evicted by the landlords "had an equitable Tide but could not be defended in a Course of Law because they were poor and . . . poor men were always oppressed by the rich." Ethan Alien's Green Mountain rebels in Vermont described themselves as "a poor people . . . fatigued in settling a wilderness country," and their opponents as "a number of Attorneys and other gentlemen, with all their tackle of ornaments, and compliments, and French finesse." Land-hungry farmers in the Hudson Valley turned to the British for support against the American landlords; the Green Mountain rebels did the same. But as the conflict with Britain intensified, the colonial leaders of the movement for independence, aware of the tendency of poor tenants to side with the British in their anger against the rich, adopted policies to win over people in the countryside… …During the Revolution, to mobilize soldiers, the tenants were promised land. A prominent landowner of Dutchess County wrote in 1777 that a promise to make tenants freeholders "would instantly bring you at least six thousand able farmers into the field." But the fanners who enlisted in the Revolution and expected to get something out of it found that, as privates in the army, they received $6.66 a month, while a colonel received $75 a month. They watched local government contractors like Melancton Smith and Mathew Paterson become rich, while the pay they received in continental currency became worthless with inflation. All this led tenants to become a threatening force in the midst of the war. Many stopped paying rent. The legislature, worried, passed a bill to confiscate Loyalist land and add four hundred new freeholders to the 1,800 already in the county. This meant a strong new voting bloc for the faction of the rich that would become anti-Federalists in 1788. Once the new landholders were brought into the privileged circle of the Revolution and seemed politically under control, their leaders, Melancton Smith and others, at first opposed to adoption of the Constitution, switched to support, and with New York ratifying, adoption was ensured. The new freeholders found that they had stopped being tenants, but were now mortgagees, paying back loans from banks instead of rent to landlords. It seems that the rebellion against British rule allowed a certain group of the colonial elite to replace those loyal to England, give some benefits to small landholders, and leave poor white working people and tenant farmers in very much their old situation. What did the Revolution mean to the Native Americans, the Indians? They had been ignored by the fine words of the Declaration, had not been considered equal, certainly not in choosing those who would govern the American territories in which they lived, nor in being able to pursue happiness as they had pursued it for centuries before the white Europeans arrived. Now, with the British out of the way, the Americans could begin the inexorable process of pushing the Indians off their lands, killing them if they resisted, in short, as Francis Jennings puts it, the white Americans were fighting against British imperial control in the East, and for their own imperialism in the West…

KEY TERMS

Colonial Hygiene Baron Friedrich von Stuben Gadsden Flag Yankee Doodle Miscellaneous Stories of the Rebellion Fallout from the American Revolution The Founding Fathers Gouverneur Morris Treaty of Six Nations Shay's Rebellion Articles of Confederation The Constitution Northwest Ordinance Homosexuality in the 18th Century The Bald Eagle Alcohol in the Late 18th Century The First American Novel The Kentucky Volunteer The Whiskey Rebellion Latinos in the Late 18th Century ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #6

The principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson was a proponent of democracy, republicanism, and individual rights, motivating American colonists to break from the Kingdom of Great Britain and form a new nation. But Jefferson lived in a planter economy largely dependent upon slavery, and as a wealthy landholder, used slave labor for his household, plantation, and workshops. He first recorded his slaveholding in 1774, when he counted 41 enslaved people. Over his lifetime he owned about 600 slaves; he inherited about 175 people while most of the remainder were people born on his plantations. Jefferson purchased some slaves in order to reunite their families, and he sold about 110 people for economic reasons; primarily slaves from his outlying farms.

Do a little digging of your own. Then answer the following question: How does this knowledge change your opinion of Thomas Jefferson? How does this hypocrisy impact the Declaration of Independence? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed