|

Module Twelve: Divisions Between North and South

Welcome to HST 201 Module Twelve! We are looking at the growing tensions between the North and South that will lead up into the American Civil War. Next rule of history: beware pseudohistory. Much like pseudoscience, a pseudohistory is a form of pseudo scholarship that attempts to distort or misrepresent the historical record, often using methods resembling legitimate historical research. Some of its characteristics are as follows: Pseudohistory is UNFALSIFIABLE or can't be proven wrong. It makes vague or unobservable claims. A classic example is "Christopher Columbus discovered America." Pseudohistory relies heavily on ANECDOTES, personal experiences, and testimonials. One great example is Clara Davis, circa 1937, waxing nostalgic about her days of bondage in Alabama. While she may miss her time as a slave, her experience is not representative of others. Pseudohistory CHERRY PICKS confirming evidence while ignoring/minimizing disconfirming evidence. Yahoo recently faced some backlash for publishing an article titled, "Chris Pratt criticized for 'white supremacist' T-shirt" after the actor was spotted wearing a shirt portraying a version of the Gadsden flag. Yahoo pinpointed some comments on social media that linked this symbol to far-right groups and white supremacy ideologies and noted that the Gadsden flag, created by American Revolutionary war general, Christopher Gadsden, portrays a racially charged message. However, while some social media posts did criticize Chris Pratt for wearing this shirt, many recognized that the flag originated in a non-racial context and therefore did not accuse Pratt of being racist. Yahoo later changed the article's name after being called out for cherry-picking some online commenters and turning their opinions into a click-bait headline. Pseudohistory uses obfuscation: Words that sound scientific but don't make sense. It consists of buzzwords, esoteric language, specialized technical terms, or technical slang that is impossible to understand for the average listener. For example, some historians will throw out some big words and fancy sentences to confuse people about what they mean. Pseudohistory lacks PLAUSIBLE MECHANISM: No way to explain it based on existing knowledge. For example, A public prosecutor says in an interview that there is "anarchy" in the land. While expressing his disappointment, this remark is made by him that he cannot prosecute someone in the imported system which has murdered another. This is because the matter has now been settled traditionally in the village by the two opposing clans. Anarchy is a relative term and hard to measure. Pseudohistory is UNCHANGING: Doesn't self-correct or progress. If we don't ever reevaluate, the dinosaurs would still drag their tails, or the Japanese internment camps of the 1940s would still be measured as a success. Pseudohistory makes EXTRAORDINARY/EXAGGERATED CLAIMS with insufficient evidence. A great example of this is the claim of Irish slavery. The claim that colonists enslaved Irish people in the British American Colonies stems from a misrepresentation of the idea of "indentured servitude." Indentured servants were people required to complete unpaid labor for a contracted period. Pseudohistory Professes CERTAINTY: Talks of "proof." with great confidence—the determination of whether a witness testified to a specific fact based on particular knowledge. A couple of examples: Caesar knew about the warriors of Gaul as he had first-hand knowledge, but does this mean he knew the various aspects of the whole tribe? Another would be: Aiden believes God spoke to him. Did God speak to him? Pseudohistory commits LOGICAL FALLACIES: arguments contain errors in reasoning. A well-known argument that Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor should have been predictable in the United States because of the many indications that an attack was imminent. This argument overlooks that there were innumerable conflicting signs that suggested possibilities other than an attack on Pearl Harbor. Only in retrospect do the warning signs seem obvious; signs which pointed in different directions tend to be forgotten. Pseudohistory Lacks PEER REVIEW and goes directly to the public, avoiding scientific scrutiny. Not to say that these sources don't include the truth. You should use them, but be wary. Examples are There are some kinds of publications that should be avoided when searching for peer-reviewed material. They are: Newspapers, Magazines, Ads or Other Sponsored Material, Editorials or Opinion Pieces, and Book Reviews Pseudohistory Claims there's a CONSPIRACY to suppress their ideas. These include Ancient aliens, ethnocentric revisionism, and historical revisionism. More on these later. This should help you avoid pitfalls in the meantime.

HIGHLIGHTS

READING

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Schweikart CHAPTER EIGHT: The House Dividing, 1848–60

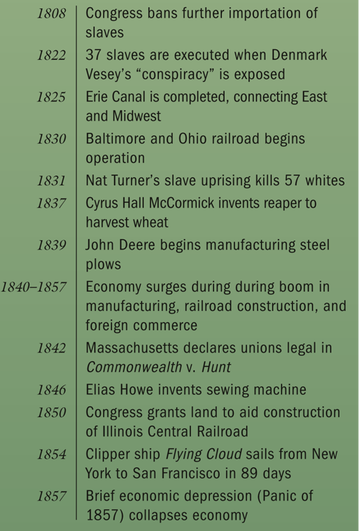

…Driven by the Declaration’s inexorable logic that “all men are created equal,” pressure rose for defenders of the slave system to explain their continued participation in the peculiar institution. John C. Calhoun, in 1838, noted that the defense of slavery had changed: This agitation [from abolitionists] has produced one happy effect; it has compelled us…to look into the nature and character of this great institution, and to correct many false impressions…. Many…once believed that [slavery] was a moral and political evil; that folly and delusion are gone; we now see it in its true light…as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world [emphasis ours]. Calhoun espoused the labor theory of value—the backbone of Marxist economic thinking—and in this he was joined by George Fitzhugh, Virginia’s leading proslavery intellectual and proponent of socialism. Fitzhugh exposed slavery as the nonmarket, anti-capitalist construct that it was by arguing that not only should all blacks be slaves, but so should most whites. “We are all cannibals,” Fitzhugh intoned, “Cannibals all!” Slaves Without Masters, the subtitle of his book Cannibals All! (1854), offered a shockingly accurate exposé of the reality of socialism—or slavery, for to Fitzhugh they were one and the same. Slavery in the South, according to Fitzhugh, scarcely differed from factory labor in the North, where the mills of Massachusetts placed their workers in a captivity as sure as the fields of Alabama. Yet African slaves, Fitzhugh maintained, probably lived better than free white workers in the North because they were liberated from decision making. A few slaves even bought into Fitzhugh’s nonsense: Harrison Berry, an Atlanta slave, published a pamphlet called Slavery and Abolitionism, as Viewed by a Georgia Slave, in which he warned slaves contemplating escape to the North that “subordination of the poor colored man [there], is greater than that of the slave South.” And, he added, “a Southern farm is the beau ideal of Communism; it is a joint concern, in which the slave consumes more than the master…and is far happier, because although the concern may fail, he is always sure of support.” Where Fitzhugh’s argument differed from that of Berry and others was in advocating slavery for whites: “Liberty is an evil which government is intended to correct,” he maintained in Sociology for the South. Like many of his Northern utopian counterparts, Fitzhugh viewed every “relationship” as a form of bondage or oppression. Marriage, parenting, and property ownership of any kind merely constituted different forms of slavery. Here, strange as it may seem, Fitzhugh had come full circle to the radical abolitionists of the North. Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Lloyd Garrison, and, earlier, Robert Owen had all contended that marriage constituted an unequal, oppressive relationship. Radical communitarian abolitionists, of course, endeavored to minimize or ignore these similarities to the South’s greatest intellectual defender of slavery. But the distinctions between Owen’s subjection to the tyranny of the commune and Fitzhugh’s “blessings” of “liberation” through the lash nearly touched, if they did not overlap, in theory. Equally ironic was the way in which Fitzhugh stood the North’s free-labor argument on its head. Lincoln and other Northerners maintained that laborers must be free to contract with anyone for their work. Free labor meant the freedom to negotiate with any employer. Fitzhugh, however, arguing that all contract labor was essentially unfree, called factory work slave labor. In an astounding inversion, he then maintained that since slaves were free from all decisions, they truly were the free laborers. Thus, northern wage labor (in his view) was slave labor, whereas actual slave labor was free labor! Aside from Fitzhugh’s more exotic defenses of slavery, religion and the law offered the two best protections available to Southerners to perpetuate human bondage. Both the Protestant churches and the Roman Catholic Church (which had a relatively minor influence in the South, except for Missouri and Louisiana) permitted or enthusiastically embraced slavery as a means to convert “heathen” Africans, and in 1822 the South Carolina Baptist Association published the first defenses of slavery that saw it as a “positive good” by biblical standards. By the mid-1800s, many Protestant leaders had come to see slavery as the only hope of salvation for Africans, thus creating the “ultimate rationalization.” Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright of New Orleans reflected this view when he wrote in 1852 that it was impossible to “Christianize the negro without the intervention of slavery.” Such a defense of slavery presented a massive dilemma, not only to the church, but also to all practicing Christians and, indeed, all Southerners: if slavery was for the purpose of Christianizing the heathen, why were there so few efforts made to evangelize blacks and, more important, to encourage them to read the Bible? Still more important, why were slaves who converted not automatically freed on the grounds that having become “new creatures” in Christ, they were now equals? To say the least, these were uncomfortable questions that most clergy and lay alike in Dixie avoided entirely. Ironically, many of the antislavery societies got their start in the South, where the first three periodicals to challenge slavery appeared, although all three soon moved to free states or Maryland. Not surprisingly, after the Nat Turner rebellion in August 1831, which left fifty-seven whites brutally murdered, many Southern churches abandoned their view that slavery was a necessary evil and accepted the desirability of slavery as a means of social control. Turner’s was not the first active resistance to slavery. Colonial precedents included the Charleston Plot, and in 1807 two shiploads of slaves starved themselves to death rather than submit to the auction block. In 1822 a South Carolina court condemned Denmark Vesey to the gallows for, it claimed, leading an uprising. Vesey, a slave who had won a lottery and purchased his freedom with the winnings, established an African Methodist Church in Charleston, which had three thousand members. Although it was taken as gospel for more than a century that Vesey actually led a rebellion, historian Michael Johnson, obtaining the original court records, has recently cast doubt on whether any slave revolt occurred at all. Johnson argues that the court, using testimony from a few slaves obtained through torture or coercion, framed Vesey and many others. Ultimately, he and thirty-five “conspirators” were hanged, but the “rebellion” may well have been a creation of the court’s. In addition to the Vesey and Nat Turner uprisings, slave runaways were becoming more common, as demonstrated by the thousands who escaped and thousands more who were hunted down and maimed or killed. Nat Turner, however, threw a different scare into Southerners because he claimed as the inspiration for his actions the prompting of the Holy Spirit. A “sign appearing in the heavens,” he told Thomas Gray, would indicate the proper time to “fight against the Serpent.” The episode brought Virginia to a turning point—emancipation or complete repression—and it chose the latter. All meetings of free blacks or mulattoes were prohibited, even “under the pretense or pretext of attending a religious meeting.” Anne Arundel County, Maryland, enacted a resolution requiring vigilante committees to visit the houses of every free black “regularly” for “prompt correction of misconduct,” or in other words, to intimidate them into staying indoors. The message of the Vesey/Turner rebellions was also clear to whites: blacks had to be kept from Christianity, and Christianity from blacks, unless a new variant of Christianity could be concocted that explained black slavery in terms of the “curse of Ham” or some other misreading of scripture. If religion constituted one pillar of proslavery enforcement, the law constituted another. Historian David Grimsted, examining riots in the antebellum period, found that by 1835 the civic disturbances had taken on a distinctly racial flavor. Nearly half of the riots in 1835 were slave or racially related, but those in the South uniquely had overtones of mob violence supported, or at the very least, tolerated, by the legal authorities. Censorship of mails and newspapers from the North, forced conscription of free Southern whites into slave patrols, and infringements on free speech all gradually laid the groundwork for the South to become a police state; meanwhile, controversies over free speech and the right of assembly gave the abolitionists the issue with which they ultimately went mainstream: the problem of white rights affected by the culture and practice of slave mastery. By addressing white rights to free speech, instead of black rights, abolitionists sanitized their views, which in many cases lay so outside the accepted norms that to fully publicize them would risk ridicule and dismissal. This had the effect of putting them on the right side of history. The free-love and communitarian movements’ association with antislavery was unfortunate and served to discredit many of the genuine Christian reformers who had stood in the vanguard of the abolition movement. No person provided a better target for Southern polemicists than William Lloyd Garrison. A meddler in the truest sense of the word, Garrison badgered his colleagues who smoked, drank, or indulged in any other habit of which he did not approve. Abandoned by his father at age three, Garrison had spent his early life in extreme poverty. Forced to sell molasses on the street and deliver wood, Garrison was steeped in insecurity. He received little education until he apprenticed with a printer, before striking out on his own. That venture failed. Undeterred, Garrison edited the National Philanthropist, a “paper devoted to the suppression of intemperance and its Kindred vices.” Provided a soapbox; Garrison proceeded to attack gambling, lotteries, Sabbath violations, and war. Garrison suddenly saw himself as a celebrity, telling others his name would be “known to the world.” In his paper Genius of Universal Emancipation, Garrison criticized a merchant involved in the slave trade who had Garrison thrown into prison for libel. That fed his martyr complex even more. Once released, Garrison joined another abolitionist paper, The Liberator, where he expressed his hatred of slavery, and of the society that permitted it—even under the Constitution—in a cascade of violent language, calling Southern congressmen “thieves” and “robbers.” Abolitionism brought Garrison into contact with other reformers, including Susan B. Anthony, the Grimké sisters, Frederick Douglass, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Each had an agenda, to be sure, but all agreed on abolition as a starting point. Garrison and Douglass eventually split over whether the Constitution should be used as a tool to eliminate slavery: Douglass answered in the affirmative, Garrison, having burned a copy of the Constitution, obviously answered in the negative…

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #13

PragerU is an American non-profit organization that creates videos on various political, economic and philosophical topics from a conservative or right-wing perspective. The videos are posted on YouTube and usually feature a speaker who lectures for about five minutes. Despite having "University" in its name, PragerU is not an academic institution, does not hold classes, and does not grant certifications or diplomas.

Colonel Ty Seidule, Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point, settles the revisionist debate. Do some research and please answer the following question with a two-paragraph minimum: What caused the Civil War? Did the North care about abolishing slavery? Did the South secede because of slavery? Or was it about something else entirely? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed