|

Module Thirteen: The American Civil War Part One

Welcome to HST 201 Module Thirteen! This is the first part of our in depth look at the American Civil War.

HIGHLIGHTS

READING

Zinn Chapter 10: The Other Civil War

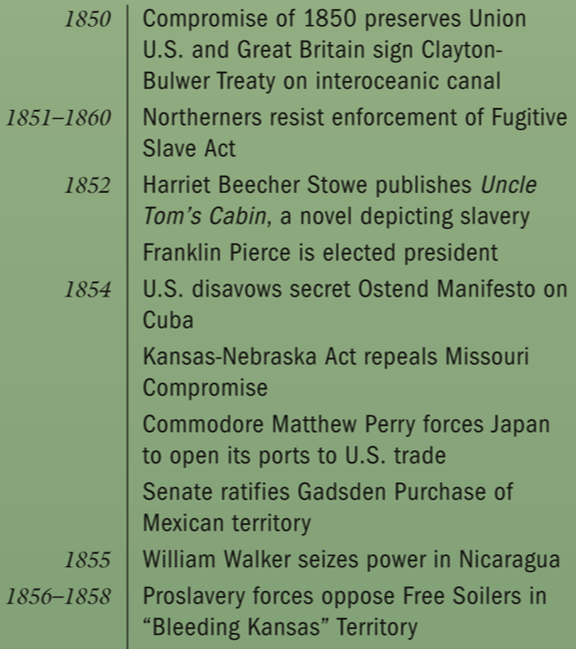

...Class-consciousness was overwhelmed during the Civil War, both North and South, by military and political unity in the crisis of war. That unity was weaned by rhetoric and enforced by arms. It was a war proclaimed as a war for liberty, but working people would be attacked by soldiers if they dared to strike, Indians would be massacred in Colorado by the U.S. army, and those daring to criticize Lincoln's policies would be put in jail without trial-perhaps thirty thousand political prisoners. Still, there were signs in both sections of dissent from that unity- anger of poor against rich, rebellion against the dominant political and economic forces. In the North, the war brought high prices for food and the necessities of life. Prices of milk, eggs, cheese were up 60 to 100 percent for families that had not been able to pay the old prices. One historian (Emerson Fite, Social and Industrial Conditions in the North during the Civil War) described the war situation: "Employers were wont to appropriate to themselves all or nearly all of the profits accruing from the higher prices, without being willing to grant to the employees a fair share of these profits through the medium of higher wages." There were strikes all over the country during the war. The Springfield Republican… said that "the workmen of almost every branch of trade have had their strikes within the last few months," and the San Francisco Evening Bulletin said "striking for higher wages is now the rage among the working people of San Francisco." Unions were being formed as a result of these strikes. Philadelphia shoemakers in 1863 announced that high prices made organization imperative. The headline in Fincher's Trades' Review of November 21, 1863, "THE REVOLUTION IN NEW YORK," was an exaggeration, but its list of labor activities was impressive evidence of the hidden resentments of the poor during the war: The upheaval of the laboring masses in New York has startled the capitalists of that city and vicinity… The machinists are making a hold stand… We publish their appeal in another column. The City Railroad employees struck for higher wages, and made the whole population, for a few days, "ride on Shank's mare."... The house painters of Brooklyn have taken steps to counteract the attempt of the bosses to reduce their wages. The house carpenters, we are informed, are pretty well "out of the woods" and their demands are generally complied with. The safe-makers have obtained an increase of wages, and are now at work. The lithographic printers are making efforts to secure better pay for their labor. The workmen on the iron clads are yet holding out against the contractors. ... The window shade painters have obtained an advance of 25 percent. The horse shoers are fortifying themselves against the evils of money and trade fluctuations. The sash and blind-makers are organized and ask their employers for 25 percent additional. The sugar packers are remodeling their list of prices. The glasscutters demand 15 percent to present wages. Imperfect as we confess our list to be, there is enough to convince the reader that the social revolution now working its way through the land must succeed, if workingmen are only true to each other. The stage drivers, to the number of 800, are on a strike… The workingmen of Boston are not behind… in addition to the strike at the Charlestown Navy Yard… The riggers are on a strike… At this writing it is rumored, says the Boston Post, that a general strike is contemplated among the workmen in the iron establishments at South Boston, and other parts of the city. The war brought many women into shops and factories, often over the objections of men who saw them driving wage scales down. In New York City, girls sewed umbrellas from six in the morning to midnight, earning $3 a week, from which employers deducted the cost of needles and thread. Girls who made cotton shirts received twenty-four cents for a twelve-hour day. In late 1863, New York working women held a mass meeting to find a solution to their problems. A Working Women's Protective Union was formed, and there was a strike of women umbrella workers in New York and Brooklyn. In Providence, Rhode Island, a Ladies Cigar Makers Union was organized. Altogether, by 1864, about 200,000 workers, men and women, were in trade unions, forming national unions in some of the trades, putting out labor newspapers. Union troops were used to break strikes. Federal soldiers were sent to Cold Springs, New York, to end a strike at a gun works where workers wanted a wage increase. Striking machinists and tailors in St. Louis were forced back to work by the army. In Tennessee, a Union general arrested and sent out of the state two hundred striking mechanics. When engineers on the Reading Railroad struck, troops broke that strike, as they did with miners in Tioga County, Pennsylvania. White workers of the North were not enthusiastic about a war which seemed to be fought for the black slave, or for the capitalist, for anyone but them. They worked in semi slave conditions themselves. They thought the war was profiting the new class of millionaires. They saw defective guns sold to the army by contractors, sand sold as sugar, rye sold as coffee, shop sweepings made into clothing and blankets, paper-soled shoes produced for soldiers at the front, navy ships made of rotting timbers, soldiers' uniforms that fell apart in the rain. The Irish working people of New York, recent immigrants, poor, looked upon with contempt by native Americans, could hardly find sympathy for the black population of the city who competed with them for jobs as longshoremen, barbers, waiters, domestic servants. Blacks, pushed out of these jobs, often were used to break strikes. Then came the war, the draft, the chance of death. And the Conscription Act of 1863 provided that the rich could avoid military service: they could pay $300 or buy a substitute. In the summer of 1863, a "Song of the Conscripts" was circulated by the thousands in New York and other cities. One stanza: We're earning, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more We leave our homes and firesides -with bleeding hearts and sore Since poverty has been our crime, we bow to thy decree; We are the poor and have no wealth to purchase liberty. When recruiting for the army began in July 1863, a mob in New York wrecked the main recruiting station. Then, for three days, crowds of white workers marched through the city, destroying buildings, factories, streetcar lines, homes. The draft riots were complex-anti-black, anti-rich, anti-Republican. From an assault on draft headquarters, the rioters went on to attacks on wealthy homes, then to the murder of blacks. They marched through the streets, forcing factories to close, recruiting more members of the mob. They set the city's colored orphan asylum on fire. They shot, burned, and hanged blacks they found in the streets. Many people were thrown into the rivers to drown. On the fourth day, Union troops returning from the Battle of Gettysburg came into the city and stopped the rioting. Perhaps four hundred people were killed. No exact figures have ever been given, but the number of lives lost was greater than in any other incident of domestic violence in American history… Listen to watch Civil War Historian Shelby Foote has to say on the Union victory:

ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #14

The "Lost Cause of the Confederacy," or simply the "Lost Cause," is an American historical negationist ideology that holds that despite losing the American Civil War, the cause of the Confederacy was a just and heroic one. The ideology endorses the supposed virtues of the antebellum South, viewing the war as a struggle primarily for the Southern way of life or "states' rights" in the face of overwhelming "northern aggression". At the same time, the Lost Cause minimizes or denies outright the central role of slavery in the outbreak of the war.

Do some research and please answer the following question with a two-paragraph minimum: From pulling the information from what you have learned about in class, why is the “Lost Cause” a folly way of thinking? Why do many still hold onto the notion of a noble war fought against “northern aggression?” Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed