|

Module Seven: Early Years of the Republic (1820 CE -1837 CE)

Welcome to HST 201 Module Seven ! We are looking at the early years of the United States. Rule number seven right out the gates: Historiography is important and is never stagnant. What does this word, which sounds like many other words and yet is still challenging to say, mean? By Wikipedia standards, historiography is the study of historians' methods in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension, it is any body of historical work on a subject. The Historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic using sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. This is a fancy way of saying that history lenses are all different as we value things differently over time. An ancient Greek historian like Herodotus will interpret data and culture much other than someone more contemporary like Howard Zinn. All voices are important, but we need to remember who and why these voices are talking. Think of all the people over time that could have contributed to historical thought that just never learned to read or write? That is a substantial missing demographic we take for granted. Things like the internet have revolutionized how we collect data and record history, a far cry from the archaic days of parchments and scrolls. Currently, history's battle lines are drawn in the sand with "traditional" and "revisionist" history. As we have seen in the other rules, history can easily be manipulated for political gains. But the term "revisionist" seems silly when you investigate our historiography. We aren't changing history; we are merely reshaping how we view history. I'll bore you later with the tedious speech of confederate statues, which I assume you already have a preconceived notion about.

HIGHLIGHTS

LECTURES

#028: Missouri Compromise, Monroe Doctrine, and the Tomato (39:09) #029: Andrew Jackson Was A Jerk! (40:28) #030: Pirates, Temperance, Trail of Tears, and Nat Turner (40:21) #031: Black Hawk War, Nullification, and Asian Americans (37:22) #032: P.T. Barnum, Texas, and the Panic of 1837 (37:01) READING

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

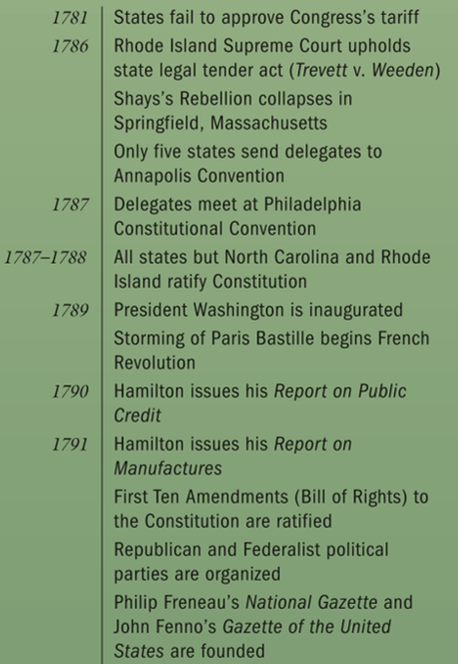

Zinn Chapter 5: “A Kind of Revolution”

At the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton suggested a President and Senate chosen for life. The Convention did not take his suggestion. But neither did it provide for popular elections, except in the case of the House of Representatives, where the qualifications were set by the state legislatures (which required property-holding for voting in almost all the states), and excluded women, Indians, slaves. The Constitution provided for Senators to be elected by the state legislators, for the President to be elected by electors chosen by the state legislators, and for the Supreme Court to be appointed by the President. The problem of democracy in the post-Revolutionary society was not, however, the Constitutional limitations on voting. It lay deeper, beyond the Constitution, in the division of society into rich and poor. For if some people had great wealth and great influence; if they had the land, the money, the newspapers, the church, the educational system- how could voting, however broad, cut into such power? There was still another problem: wasn't it the nature of representative government, even when most broadly based, to be conservative, to prevent tumultuous change? It came time to ratify the Constitution, to submit to a vote in state conventions, with approval of nine of the thirteen required to ratify it. In New York, where debate over ratification was intense, a series of newspaper articles appeared, anonymously, and they tell us much about the nature of the Constitution. These articles, favoring adoption of the Constitution, were written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, and came to be known as the Federalist Papers (opponents of the Constitution became known as anti-Federalists). In Federalist Paper #10, James Madison argued that representative government was needed to maintain peace in a society ridden by factional disputes. These disputes came from "the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society." The problem, he said, was how to control the factional struggles that came from inequalities in wealth. Minority factions could be controlled, he said, by the principle that decisions would be by vote of the majority. So the real problem, according to Madison, was a majority faction, and here the solution was offered by the Constitution, to have "an extensive republic," that is, a large nation ranging over thirteen states, for then "it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.... The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States." Madison's argument can be seen as a sensible argument for having a government which can maintain peace and avoid continuous disorder. But is it the aim of government simply to maintain order, as a referee, between two equally matched fighters? Or is it that government has some special interest in maintaining a certain kind of order, a certain distribution of power and wealth, a distribution in which government officials are not neutral referees but participants? In that case, the disorder they might worry about is the disorder of popular rebellion against those monopolizing the society's wealth. This interpretation makes sense when one looks at the economic interests, the social backgrounds, of the makers of the Constitution.

KEY TERMS

Missouri Compromise The Tomato College of Pharmacy Monroe Doctrine Fannie Hill John Neal and the Gymnasium Noah Webster Jr. Jackson's Inaugural Party Liberia The Petticoat Affair The Tariff of Abominations Indian Removal Act of 1830 Piracy Part 3 Temperance Movement Begins The Trail of Tears The Book of Mormon Nat Turner Black Hawk War Nullification Crisis Unique American Style Afong Moy P.T. Barnum Texas Revolution Samuel Colt Panic of 1837 Elijah P. Lovejoy ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #8

Hamilton: An American Musical is a sung-and-rapped through musical about the life of American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, with music, lyrics, and book by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Incorporating hip-hop, R&B, pop, soul, traditional-style show tunes, and color-conscious casting of non-white actors as the Founding Fathers and other historical figures, the musical achieved both critical acclaim and box office success.

Listen to these dope rhymes and answer the following question: Scholars have debated whether “Hamilton” over-glorifies the man, inflating his opposition to slavery while glossing over less attractive aspects of his politics. However, even among historians who love the musical and its multiethnic cast, a question is asked: does “Hamilton” really get Hamilton right? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed