|

Module Two: Colonial Age Part 1 Goals of Colonization, Spain, and France (1585CE-1701CE)

Welcome to HST 201 Module Two! We are looking at North America post first contact with Europe. There is a common myth that lingers within the historical community. Every year I ask my students whether they enjoy history or not. Generally, I get a good mixed of enjoyment juxtaposed with physical anguish. If I press further and see WHY they hate studying history, the overwhelming answer is that history never changes. It’s boring. Well, I am here to put that baby to bed with rule number two of history: History is always changing. If we were to receive all our information from a textbook written 30 years ago, then yes, history doesn’t change. But as we discover more artifacts buried in mountain side, or we invite more perspectives to the table (much like the 1619 Project), history becomes a tad more elastic.

HIGHLIGHTS

LECTURES

READING

My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Schweikart, Chapter 1 “The City on the Hill, 1492-1707”

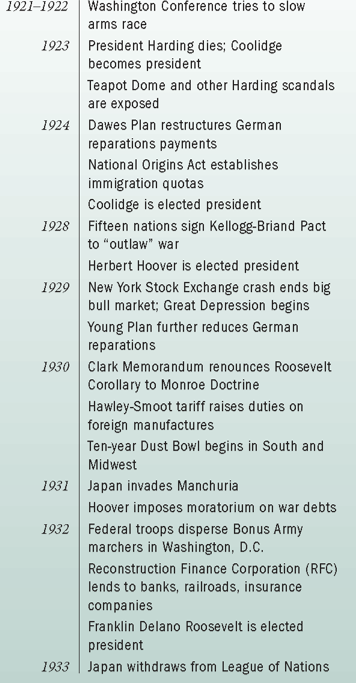

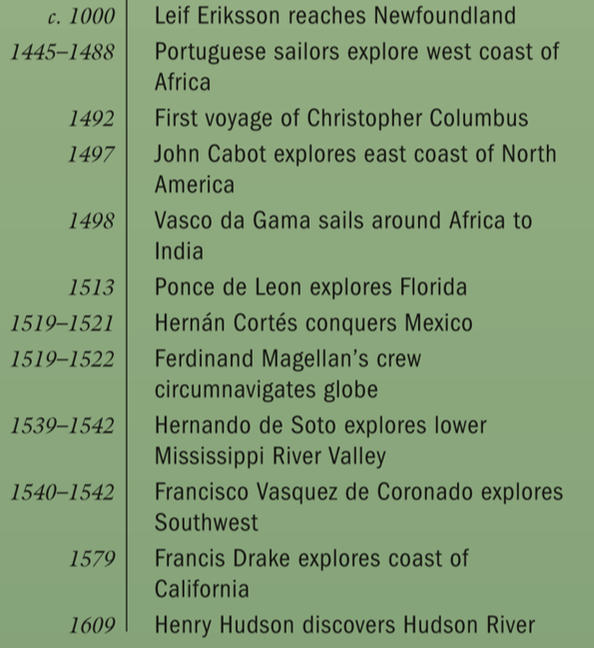

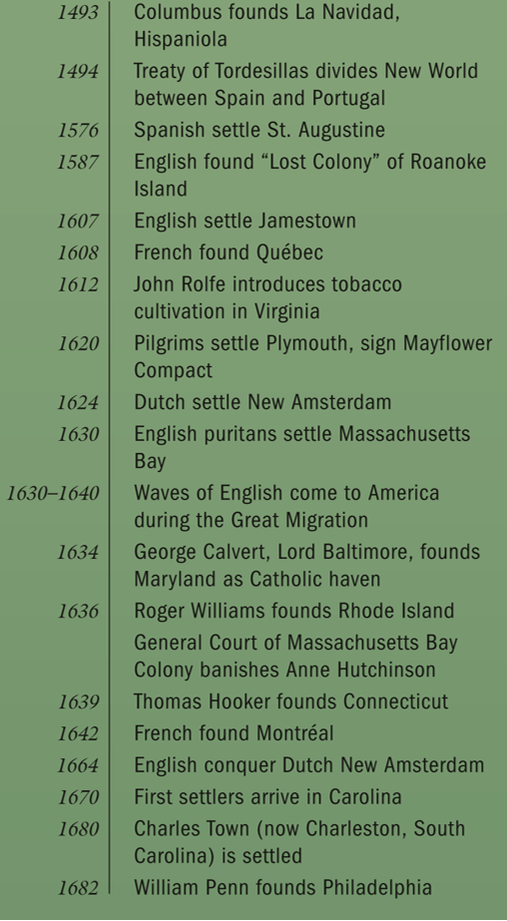

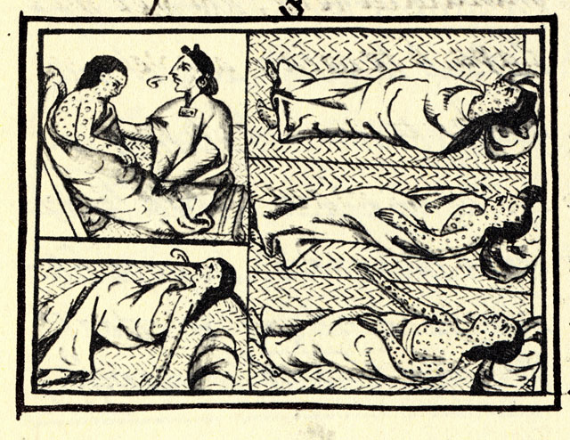

God, glory, and gold—not necessarily in that order—took post-Renaissance Europeans to parts of the globe they had never before seen. The opportunity to gain materially while bringing the Gospel to non-Christians offered powerful incentives to explorers from Portugal, Spain, England, and France to embark on dangerous voyages of discovery in the 1400s. Certainly they were not the first to sail to the Western Hemisphere: Norse sailors reached the coasts of Iceland in 874 and Greenland a century later, and legends recorded Leif Erickson’s establishment of a colony in Vinland, somewhere on the northern Canadian coast. Whatever the fate of Vinland, its historical impact was minimal, and significant voyages of discovery did not occur for more than five hundred years, when trade with the Orient beckoned… …The five-hundred-year anniversary of Columbus’s discovery was marked by unusual and strident controversy. Rising up to challenge the intrepid voyager’s courage and vision—as well as the establishment of European civilization in the New World—was a crescendo of damnation, which posited that the Genoese navigator was a mass murderer akin to Adolf Hitler. Even the establishment of European outposts was, according to the revisionist critique, a regrettable development. Although this division of interpretations no doubt confused and dampened many a Columbian festival in 1992, it also elicited a most intriguing historical debate: did the esteemed Admiral of the Ocean Sea kill almost all the Indians? A number of recent scholarly studies have dispelled or at least substantially modified many of the numbers generated by the anti-Columbus groups, although other new research has actually increased them. Why the sharp inconsistencies? One recent scholar, examining the major assessments of numbers, points to at least nine different measurement methods, including the time-worn favorite, guesstimates. 1. Pre-Columbian native population numbers are much smaller than critics have maintained. For example, one author claims “Approximately 56 million people died as a result of European exploration in the New World.” For that to have occurred, however, one must start with early estimates for the population of the Western Hemisphere at nearly 100 million. Recent research suggests that that number is vastly inflated, and that the most reliable figure is nearer 53 million, and even that estimate falls with each new publication. Since 1976 alone, experts have lowered their estimates by 4 million. Some scholars have even seen those figures as wildly inflated, and several studies put the native population of North America alone within a range of 8.5 million (the highest) to a low estimate of 1.8 million. If the latter number is true, it means that the “holocaust” or “depopulation” that occurred was one fiftieth of the original estimates, or 800,000 Indians who died from disease and firearms. Although that number is a universe away from the estimates of 50 to 60 million deaths that some researchers have trumpeted, it still represented a destruction of half the native population. Even then, the guesstimates involve such things as accounting for the effects of epidemics—which other researchers, using the same data, dispute ever occurred—or expanding the sample area to all of North and Central America. However, estimating the number of people alive in a region five hundred years ago has proven difficult, and recently several researchers have called into question most early estimates. For example, one method many scholars have used to arrive at population numbers—extrapolating from early explorers’ estimates of populations they could count—has been challenged by archaeological studies of the Amazon basin, where dense settlements were once thought to exist. Work in the area by Betty Meggers concludes that the early explorers’ estimates were exaggerated and that no evidence of large populations in that region exists. N. D. Cook’s demographic research on the Inca in Peru showed that the population could have been as high as 15 million or as low as 4 million, suggesting that the measurement mechanisms have a “plus or minus reliability factor” of 400 percent! Such “minor” exaggerations as the tendencies of some explorers to overestimate their opponents’ numbers, which, when factored throughout numerous villages, then into entire populations, had led to overestimates of millions. 2. Native populations had epidemics long before Europeans arrived. A recent study of more than12,500 skeletons from sixty-five sites found that native health was on a “downward trajectory long before Columbus arrived.” Some suggest that Indians may have had a nonvenereal form of syphilis, and almost all agree that a variety of infections were widespread. Tuberculosis existed in Central and North America long before the Spanish appeared, as did herpes, polio, tick-borne fevers, giardiasis, and amebic dysentery. One admittedly controversial study by Henry Dobyns in Current Anthropology in 1966 later fleshed out over the years into his book, argued that extensive epidemics swept North America before Europeans arrived. As one authority summed up the research, “Though the Old World was to contribute to its diseases, the New World certainly was not the Garden of Eden some have depicted.” As one might expect, others challenged Dobyns and the “early epidemic” school, but the point remains that experts are divided. Many now discount the notion that huge epidemics swept through Central and North America; smallpox, in particular, did not seem to spread as a pandemic. 3. There is little evidence available for estimating the numbers of people lost in warfare prior to the Europeans because in general natives did not keep written records. Later, when whites could document oral histories during the Indian wars on the western frontier, they found that different tribes exaggerated their accounts of battles in totally different ways, depending on tribal custom. Some, who preferred to emphasize bravery over brains, inflated casualty numbers. Others, viewing large body counts as a sign of weakness, deemphasized their losses. What is certain is that vast numbers of natives were killed by other natives, and that only technological backwardness—the absence of guns, for example—prevented the numbers of natives killed by other natives from growing even higher. 4. Large areas of Mexico and the Southwest were depopulated more than a hundred years before the arrival of Columbus. According to a recent source, “The majority of Southwesternists…believe that many areas of the Greater Southwest were abandoned or largely depopulated over a century before Columbus’s fateful discovery, as a result of climatic shifts, warfare, resource mismanagement, and other causes.” Indeed, a new generation of scholars puts more credence in early Spanish explorers’ observations of widespread ruins and decaying “great houses” that they contended had been abandoned for years. 5. European scholars have long appreciated the dynamic of small-state diplomacy, such as was involved in the Italian or German small states in the nineteenth century. What has been missing from the discussions about native populations has been a recognition that in many ways the tribes resembled the small states in Europe: they concerned themselves more with traditional enemies (other tribes) than with new ones (whites)…

KEY TERMS

Roanoke Colony Joachim Gans Colonials and Fitness Food in the New World Epidemic Disease French Colonization Part 2 Dutch Mid-Atlantic Squanto 17th Century Music Alcohol Headright System Tobacco Brides 1619-African Slavery Pocahontas Cecily Jordan Farrar The Mayflower New Sweden Indentured Servitude House Wives in the New World 17th Century Literature 17th Century Philosophy Jamestown Anne Hutchinson Piracy Part One Documented Slavery Beaver Wars ASSIGNMENTS

Forum Discussion #3

Now that we have read both People's History of the United States and Patriot's History of the United States, we need to delve into both works to uncover the truth. Please answer the following question with a two-paragraph minimum:

Compare and contrast Chapter 1 of Zinn and Chapter 1 of Schweikart. what are some things they agree upon? What are some things they disagree on? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed