|

Week 2: The Gilded Age

Welcome to HST 202 Week Two! This is the second learning module looking at the United States in the Gilded Age. There is a common myth that lingers within the historical community. Every year I ask my students whether they enjoy history or not. Generally, I get a good mixed of enjoyment juxtaposed with physical anguish. If I press further and see WHY they hate studying history, the overwhelming answer is that history never changes. It’s boring. Well, I am here to put that baby to bed with rule number two of history: History is always changing. If we were to receive all our information from a textbook written 30 years ago, then yes, history doesn’t change. But as we discover more artifacts buried in mountain side, or we invite more perspectives to the table (much like the 1619 Project), history becomes a tad more elastic.

HIGHLIGHTS

READING

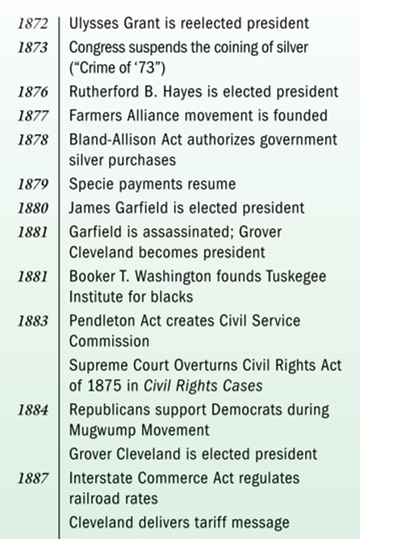

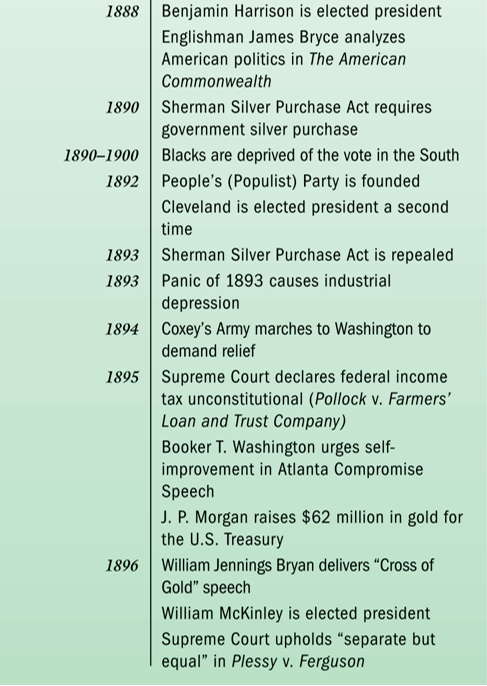

Carnes, Chapter 20: From Smoke-filled Rooms to Prairie Wildfires 1877-1896 My classes utilize both Howard Zinn's Patriot's History of the United States and Larry Schweikart's Patriot's History of the United States, mostly in excerpts posted to the modules. You can access the full text of People's History or Patriot's History by clicking on the links.

Schweikart Chapter 12: Sinews of Democracy, 1876–96

…While farmers agitated over silver, another large group of people—immigrants—flooded into the seaport cities in search of a new life. Occasionally, they were fleeced or organized by local politicians when they arrived. Often they melted into the American pot by starting businesses, shaping the culture, and transforming urban areas. In the process the cities lost their antebellum identities, becoming true centers of commerce, arts, and the economy, as well as hotbeds of crime, corruption and degeneracy—“a serious menace to our civilization,” warned the Reverend Josiah Strong in 1885.62 The cities, he intoned, were “where the forces of evil are massed,” and they were under attack by “the demoralizing and pauperizing power of the saloons and their debauching influence in politics,” not to mention the population, whose character was “so largely foreign, [and where] Romanism finds its chief strength.” The clergyman probably underestimated the decay: in 1873, within three miles of New York’s city hall, one survey counted more than four hundred brothels housing ten times that number of prostitutes. Such illicit behavior coincided with the highest alcohol consumption levels since the turn of the century, or a quart of whiskey a week for every adult American. Some level of social and political pathology was inevitable in any population, but it was exacerbated by the gigantic size of the cities. By the 1850s, the more partisan of the cities, especially New York and Boston, achieved growth in spite of the graft of the machines and the hooliganism. New York (the largest American city after 1820), Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston emerged as commercial hubs, with a second tier of cities, including New Orleans, Cincinnati, Providence, Atlanta, Richmond, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland developing strong urban areas of the irown. But New York, Boston, Chicago, and New Orleans, especially, also benefited from being regional money centers, further accelerating their influence by bringing to the cities herds of accountants, bankers, lawyers, and related professionals. By the mid-1800s, multistory buildings were commonplace, predating the pure skyscraper conceived by Louis Sullivan in 1890. Even before then, by mid-century two-story developments and multiuse buildings done in the London style had proliferated. These warehouses and factories soon yielded to larger structures made of brick (such as the Montauk buildings of Chicago in 1882) or combinations of masonry hung on a metal structure. Then, after Andrew Carnegie managed to produce good cheap steel, buildings were constructed out of that metal. More than a few stories, however, required another invention, the electric safety-brake-equipped elevator conceived by Elisha Otis. After Otis demonstrated his safety brake in 1887, tall buildings with convenient access proliferated, including the Burnham & Root, Adler & Sullivan, and Holabird & Roche buildings in Chicago, all of which featured steel frames. Large buildings not only housed businesses, but also entertainments: the Chicago Auditorium (1890) was ten stories high and included a hotel. After 1893 the Chicago city government prohibited buildings of more than ten stories, a prohibition that lasted for several decades. If the cities of the late 1800s fulfilled Jefferson’s worst nightmares, they might have been worse had the crime and graft not been constrained by a new religious awakening…

ASSIGNMENTS

Remember all assignments, tests and quizzes must be submitted official via BLACKBOARD Forum Discussion #2

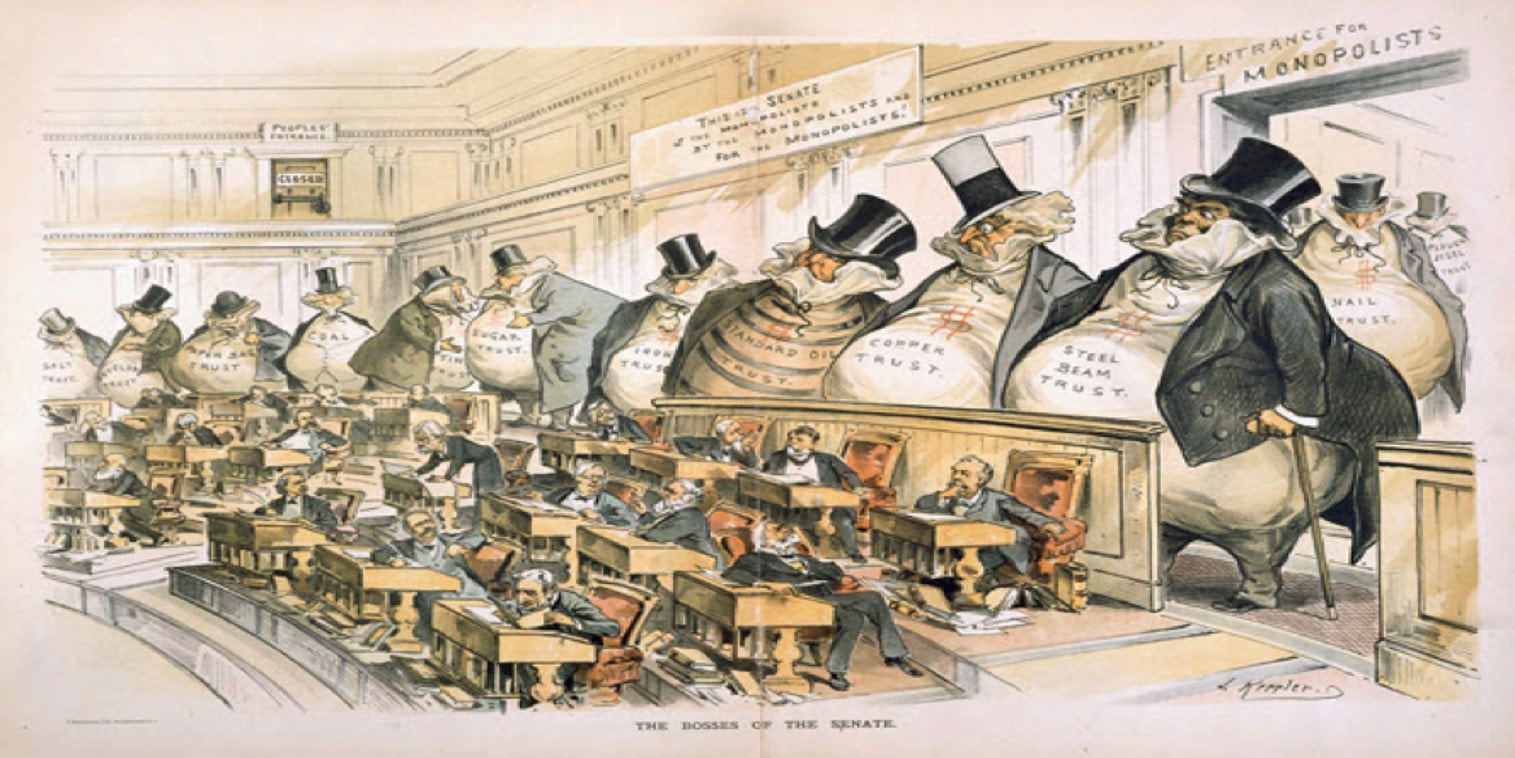

The term Gilded Age for the period of economic boom after the American Civil War up to the turn of the century was applied to the era by historians in the 1920s, who took the term from one of Mark Twain's lesser-known novels, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. The book satirized the promised "golden age" after the Civil War, portrayed as an era of serious social problems masked by a thin gold gilding of economic expansion. In the 1920s and '30s the metaphor "Gilded Age" began to be applied to a designated period in American history. By this, he meant that the period was glittering on the surface but corrupt underneath.

The Hells Canyon massacre was a massacre where thirty-four Chinese gold miners were ambushed and murdered in May 1887. Watch the video above and answer the following question: How does the Mark Twain's take on the Gilded Age relate to race relations in the late 19th century? Need help? Remember the Discussion Board Rubric.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRyan Lancaster wears many hats. Dive into his website to learn about history, sports, and more! Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed